Published on

Human Skills: Critical Components of Future Work

It is no secret that the workplace is changing. The shelf life of new technical skills is estimated to be three years (Auger, 2019), with core digital skills changing even faster. Today’s rapid changes in science and technology make it challenging to predict tomorrow’s skills more than a few years in advance. Even the most technologically skilled individuals will need to refresh their technical skills multiple times during their careers. This state of affairs demands some deep thinking about what workers really need to prepare for the future of work.

Although predicting future technical skills may present a challenge for those involved in educational planning, our literature review and interviews with experts revealed that non-technical skills will always be important. Whether we refer to them as non-technical skills, soft skills, power skills, or the myriad of other names assigned to them, these are the capabilities that are uniquely human and will outlast the declining shelf life of technical skills. Human skills—for example, critical thinking, adaptability, collaboration or strategic visioning—serve as the binding agents, or glue, that will support the ever-changing list of required technical skills. Expertise in human skills will become even more critical as we adapt to rapid changes in science, technology and the digital economy (Selingo, 2018; WEF, 2016). In the foreseeable future, automated decision systems or sophisticated robotic systems will still require a human counterpart who can show empathy, negotiate or think critically about complex problems.

While most experts agree on the need for human skills in the workplace, their opinions differ greatly on which skills are important. Numerous frameworks identify many different skills as priorities. Employers and educators need direction regarding which skills are most important. What should guide planning for workforce education and training? What non-technical skills are key to a worker’s ability to constantly adapt to and perform well in the hybrid jobs of the future?

Individuals face similar questions as they consider skills training to advance their careers. Which human skills might provide the greatest return on their investment of time and energy? Which skills will transfer across multiple careers and disciplines?

A team from MIT’s Jameel World Education Lab has embarked on an exciting project that provides useful answers to the above questions. Long recognized as a leader in research, innovation, and technology development, MIT launched J-WEL to transform the processes of learning around the world. This commitment motivated development of the Human Skills Matrix, which summarizes the non-technical skills and attributes that workers will need, in addition to their specialized technical skills, to thrive in today’s rapidly evolving organizations. The matrix is not a framework specifically targeted toward industry, education or one geographic area; rather, it crosscuts all of those categories, providing a guide to skills that are foundational to the success of every individual.

The MIT J-WEL Human Skills Matrix (HSX) was conceptualized from more than a year of research. We surveyed the literature, examining work already conducted in the domain. We interviewed MIT faculty, employers and other thought leaders about skills needed to adapt to future jobs. We then analyzed 41 frameworks and reports published by multiple entities—HR firms, corporations, educational organizations and institutions, research partnerships between educational institutions and corporations, labor organizations, social media surveys, and government organizations. We examined the commonalities between the various sources and found some overlap as well as divergence.

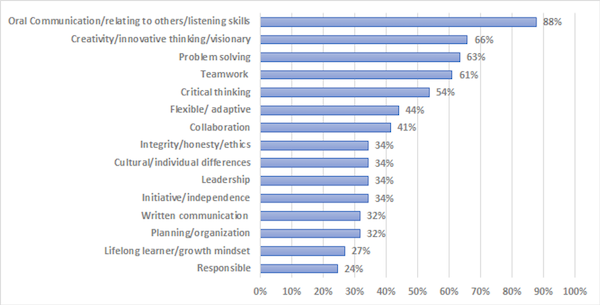

Communication skills topped the list, appearing in 88% of the 41 sources. This was followed by creativity (66%), problem solving (63%), teamwork (61%) and critical thinking (54%). Our analysis of the literature, other frameworks and interviews produced a list of 44 items across four categories of skills.

To refine and validate our list, we conducted an online Q-sort, a qualitative research methodology that statistically analyzes participants’ ranking of skills. Thirty individuals— experts from human resources, post-secondary education, workforce, public policy and research—participated in this phase of the research. Taken together, our findings led to the development of the 2 x 2 Human Skills Matrix containing 24 skills focused on four seminal areas: thinking, managing ourselves, interacting and leading.

A distinguishing feature of the MIT J-WEL Human Skills Matrix is the meta-level or thematic grouping of skills in the four quadrants. The skills in the top row are applied (thinking and interacting), and the skills in the bottom row are managed (in ourselves and others). Similarly, the skills in the left-hand column are intrapersonal skills (within ourselves), and the ones in the right-hand column are interpersonal skills (with others).

The matrix is also unique in that all four quadrants contain skills that point toward the future and that are often absent from other frameworks. It calls out Thinking and Leading as two important quadrants. Critical thinking has long been recognized as a necessary skill, but to navigate our complex and interconnected world of tomorrow, other ways of thinking will be central to success. Our matrix points to these additional ways of thinking. Individuals must not only think critically when confronted with new information or solving difficult problems, but they will need to use systems, thinking and possess comfort with ambiguity as well. Workers at all levels and across domains need to understand how the actions of one system—a group of workers, business unit or department—may affect the actions of other systems within the larger system. Similarly, we argue that leading others is important to workers in all positions and at all levels of an organization, whether it is conveying a strategy for surpassing quality improvement targets to one’s co-workers on an assembly line, or conveying a strategy for increasing market share to mid-level managers as the company CEO.

In the Interacting quadrant, our matrix identifies empathy and relationship curation as critical skills in addition to the important and often named skills of communication and collaboration. With rapid changes in the workplace and an increased use of technology for communication, tomorrow’s workers must be adept at developing a rapport with others, and then maintaining those relationships to foster exchange of ideas for mutual benefit.

The Managing ourselves quadrant contains self-awareness as one of the key skills necessary for workplace success. Through self-awareness, workers can realize their strengths or weaknesses and can then use this assessment as a basis for action.

Foundational to the human skills named in the matrix are the “literacies” which are listed around the border. In addition to specific content or technical knowledge, workers must be able to make informed decisions about financial resources (financial literacy), participate in or initiate change within the community (civic literacy), interact effectively with individuals from diverse backgrounds (cultural literacy), function effectively via digital platforms (digital literacy), and know how things get accomplished within an organization (organizational literacy). A basic understanding of these domains is essential to workers’ use of human skills in a given context. Although we did not specifically call them out in the matrix, we considered reading, writing and mathematical skills as basic skills required for success in the workplace.

We expect the MIT J-WEL Human Skills Matrix to be useful for organizations or institutions that are engaged in planning and developing workforce education, or for individuals thinking about advancing or changing their careers. For the worker who wants to upskill or reskill, the HSX can help them to identify where to begin, as the skills we have identified will traverse disciplines at all levels of authority or responsibility. Employers and educators can utilize the matrix as they plan curriculum or professional development activities. The organization of skills into four quadrants allows for grouping into theme-based pillars of action that can be emphasized. For example, a strand of workplace education could focus on Interacting skills for one quarter with activities focused on those skills. Alternatively, each course in a curriculum could be designed to deliver the specific topic as well as opportunities to exercise and improve upon one or more human skills.

This matrix is just the start. We are building tools to teach and assess the skills in collaboration with interested parties around the world. For example, we have developed and tested a one-day workshop for workers, students, or interested adults. Through role play, reflection and discussion, workshop participants can familiarize themselves with selected human skills from the MIT J-WEL matrix, obtain expert and peer feedback on their utilization of those skills, and plan next steps in their quest for improvement. We are currently extending this work with digital tools, additional role plays and stories of human skills in different environments.

To become involved in this exciting project, we invite you to investigate the MIT J-WEL Human Skills Matrix. The website houses our matrix, workshop materials and valuable bite-sized activities that you can easily implement in your organization to hone workers’ skills.

Think about how the matrix fits with or enhances your curriculum, professional development, or skills training programs. Try it out as you plan educational opportunities for students or workers. Use and adapt our workshop curriculum to fit your context. If you would like to use these assets, provide comments for improvement, or even work with us to extend them to new areas, please contact us. Join us in this bold effort to prepare workers for the future!

– – – –

References:

Auger, Jeremy (2019, May). The Future of Skills in the 21st Century. D2L News https://www.d2l.com/blog/the-future-of-skills-in-the-21st-century/

Selingo, Jeffrey. (2018, October) The new job for life: Learning. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2018/10/12/new-job-life-learning/

WEF. (2016, January). The future of jobs: Employment, skills and workforce strategy for the fourth industrial revolution. In Global Challenge Insight Report, World Economic Forum, Geneva. Retrieved from http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Future_of_Jobs.pdf

Author Perspective: Administrator

Author Perspective: Analyst