Published on

Competency-Based Education: A Model For Keeping Up in Canada

Most students enrolled in Canadian colleges and universities today should expect to return to school down the road—probably several times, hopefully for shorter, more flexible and affordable programs.

That’s because, each year, the graduates of our higher education programs are entering a different workforce than the one their predecessors did. Disruptors like globalization and automation, and the fact that we are living longer lives are causing the economy to change faster than ever before.

This change isn’t necessarily negative. Historically, technology has created more jobs than it’s destroyed, while globalization has brought about as many opportunities as it has challenges. For students and workers, staying ahead in this time of unpredictability will mean adapting, learning new skills often and embracing new technologies regularly. We can do that with the help of a responsive postsecondary system, modeled around lifelong learning.

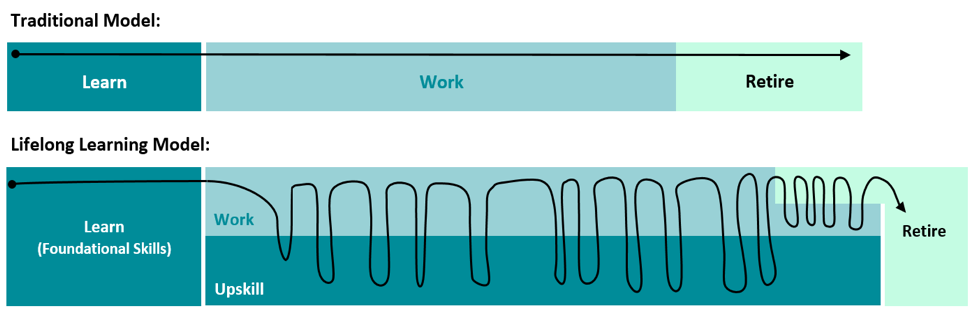

Traditionally, our education system has banked on students gaining the knowledge and skills they’ll need for their working lives by earning their college diploma or university degree at the outset of their career. It’s a model that worked well for many years. But succeeding in today’s rapidly changing economy will depend on a new model, where the initial learning experience is as much about developing knowledge and skills for a specific career as it is about learning how to learn; and developing transferable skills (like communication, problem solving and initiative) and an appetite for learning that will position learners to develop new skills and knowledge, as needed, later on.

The lifelong learning model prepares students, as Heather McGowan puts it, “to lose their jobs. Often.” Rather than acting as a linear pipeline to a specific job, a modern system of lifelong learning develops transferable skills early, in K-12 and postsecondary, and tops up that foundational schooling with job-specific skills, via short, flexible programs, throughout our working lives.

Figure 1: The Lifelong Learning Model

We have some work to do in embracing this model. In the province of Ontario, Canada, where my workplace is based and research is focused, higher education may be falling short on both these fronts: developing foundational skills and offering upskilling opportunities for mature learners with previous postsecondary experience.

Our business leaders, like those in the U.S., have indicated in numerous surveys (here’s one example) that the transferable skills of recent graduates aren’t up to snuff. And students themselves have said they feel the same. Our survey of more than 6,000 college and university students showed a perceived discrepancy between the transferable skills students are developing in the classroom and the ones they’ll need in the workplace. Our pilot skills assessments showed little difference between the literacy, numeracy and critical-thinking skill levels of students entering and graduating from postsecondary programs, suggesting that there is room to improve our teaching.

Looking beyond the foundation, it seems the “lifelong” piece of the learning puzzle is also lacking. Our publicly funded postsecondary institutions need to offer more of the short, affordable and flexible programs our adult learners will increasingly need. I’m confident they can do so.

Our colleges and universities have centuries-long experience teaching and driving innovation. They are uniquely qualified to meet the needs of students at all stages of the lifelong learning model. And the competency-based programs that have emerged south of the border are excellent inspiration for doing so.

Competency-based education (CBE) focuses on what students know and can do. CBE programs are often online, and provide students with resources, such as learning coaches and video tutorials, to develop and demonstrate knowledge and skills at their own pace. Graduates of these programs don’t just pass, they have to master the assessments. (For a crash course in CBE, check out this 3 minute video by the University of Wisconsin.)

CBE programs are flexible and designed to meet the needs of mature learners juggling responsibilities like childcare and work. The programs typically have variable starting points throughout the year. Some institutions even operate on a subscription “all-you-can-learn” model, and they recognize prior learning so experienced students can graduate faster.

Employers are often involved in designing CBE programs, and assignments tend to align with real-world expectations (accounting students, for example, might be asked to analyze a balance sheet).

These features—flexibility, recognition of prior learning, alignment with employer expectations—are all appealing to the adult worker in today’s world of constant change, looking for skills-upgrading to advance or pivot in a career.

And, given the threat of declining domestic enrollments and questions around institutional sustainability, it seems Canadian institutions should be eager to tap into a growing and underserved market of adult learners. I suspect our American counterparts will want to expand this type of programming for similar reasons. And while the impetus in the U.S. may have been to support the many Americans who have had to abandon their studies before earning a credential, U.S. institutions may also want to consider introducing new programs tailored to the growing numbers of highly educated adults looking to upskill or reskill.

So, how do we facilitate the delivery of these programs in Canada? Some ideas come to my mind: collaboration, support from government and engagement with employers.

Last year, my colleague and I interviewed American leaders in the world of CBE and heard repeatedly how much the quality and success of the programs have depended on C-BEN, a network of U.S. institutions sharing knowledge and tools. Our provincial and federal governments can play a role in facilitating a similar camaraderie among institutions in Canada by funding pilot projects and establishing processes for sharing the innovations that come out of them (through something like C-BEN’s CBExchange). Postsecondary institutions and faculty could facilitate the same by being open to learning and growing together.

Provincial governments can also facilitate CBE-style program development by loosening funding and regulatory restrains, making it easier for higher education institutions to develop and deliver flexible programs geared to adults. At the same time, government workforce development programs—like Second Career, which helps displaced workers who have little or no postsecondary education pay for training—will need to adapt to serve a broader group of adults. As more workers become vulnerable to displacement and disruption, it’s no longer primarily the lowest skilled who will need support. More middle-skilled and highly skilled workers will need improved access to upskilling and re-skilling programs as well.

And employers will need to join educators and governments at the table. They’ll need to participate in the process of defining the competencies that are required for success, designing relevant assessments and recognizing new forms of credentials.

Meanwhile, educators at all levels can learn from the CBE philosophy. Rather than grading on a curve, CBE instructors aim to see all students develop the skills needed to succeed outside of the classroom. So while CBE programs aren’t meant for everyone—it takes maturity and motivation to learn independently—the underlying idea that with the right resources and support, all students can eventually master material, is something students in traditional and non-traditional programs could benefit from at all stages of their learning lives.

Author Perspective: Analyst