Published on

Identifying and Using Levers for Institutional Culture Change to Eliminate Equity Gaps in Student Success

The United States is rapidly reaching the point at which the relatively low levels of education attainment among its adult population will create both social and economic crises. As a matter of policy and philosophy the country is placing more and more critical decisions in the hands of individual citizens, like decisions surrounding choices about their own health care. These matters are so complex that individuals without education beyond high school will be without the tools necessary to make informed decisions about issues that affect their lives in fundamental and profound ways. Similarly, the competitiveness of state and national economies will demand a workforce with higher and higher levels of knowledge and skills. Pleas come daily from employers for workers who can fill the skills gaps. We need to re-think how our higher education institutions can effectively serve a much broader set of students than the ones for whom they were originally designed.

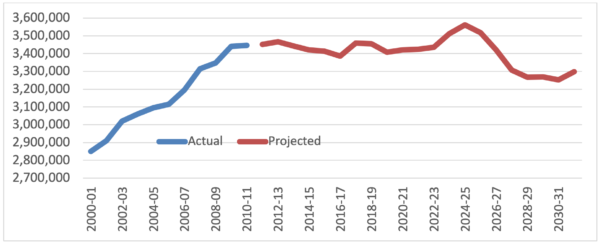

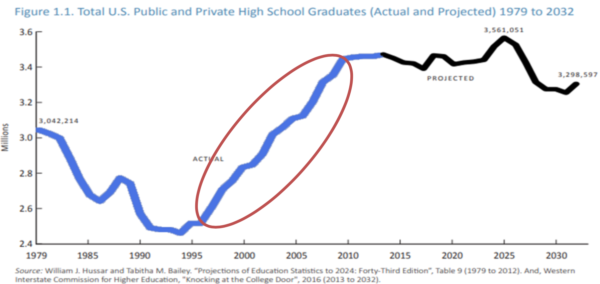

As the graph below shows (from WICHE’s 2016 Knocking at the College Door [i]), in nine years, the number of high school graduates in the U.S. will hit a low point in most states. These young people are already in elementary school, so this is not a prediction but a reality. That means there will be hundreds of thousands fewer high school graduates seeking college and university education. There are no indications these numbers will radically change beyond 2019.

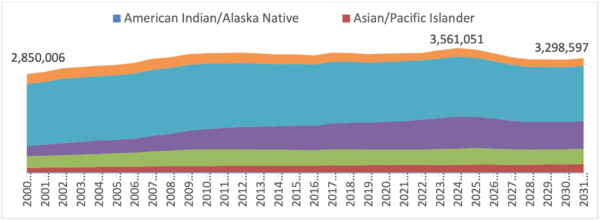

The only reason that decline is not even greater is increases in numbers of nonwhite high school graduates as the graph below shows. The reality is that our colleges and universities can no longer count on growth but must refocus on providing exemplary services to fewer and new types of students.

Since the majority of all postsecondary students tend to be enrolled in public institutions [ii], the planning for this shift will have an effect on both institutions and state policymaking. Planners in several states are already realizing the need to shift away from incentives encouraging accommodation to demand growth—like access-focused initiatives—which were appropriate to the circumstances of the late 1990’s and early 2000’s (see graph below). Recognizing the demographic shifts, some state planners are beginning to use performance funding models that encourage success in serving traditionally underserved populations. These underserved populations must be served in much larger numbers, and they must have their skills upgraded periodically, if workforce needs are to be met.

By looking at a longer time period than the first figure, it is apparent that the increases in high school graduates were dramatic from the late 1990’s to the early 2000’s. Even more important is the observation that NCHEMS Vice President Brian Prescott made, that not only were many higher education policies set in stone during that time, it is when most postsecondary leaders came into the field. They learned how to manage campuses and state systems at a time when access was the major issue. Very few have training for or experience with accommodating the new realities. They are now challenged to lead mature institutions [iii] that need to focus less on providing more access to recent high school graduates and more on serving a different set of students very well. In addition to the changes in the ways new traditionally aged students use and regard technologies, these mature institutions must adapt their practices for students of different income levels, preparation, ethnicities and ages. The observation above regarding leaders also applies to faculty members, most of whom are still focusing on bringing more students into their academic programs that can translate to more resources for their departments. Rarely is there any interest in downsizing academic programs.

States are beginning to adopt financing schemes that shift from numbers enrolled to numbers of students who succeed. Yet there are very few roadmaps to help academic staff, support staff and administrators get started in this complete change of campus culture. We have less than a decade to accomplish these changes if our higher education institutions are to thrive in a very different world.

The Foundation for Student Success Board members agree that lasting institutional culture change takes time—8 to 10 years—but once it is accomplished, it outlasts the original instigative leaders. For many reasons, including being prepared for the coming demographic shifts, we must embrace equity gap eliminations for underrepresented and underserved students. We need to start changing campus practices now if our broader communities are to be able to take full advantage of postsecondary education benefits.

After two years of practical research with 28 public institutions of various types (urban, rural, research universities, community colleges, comprehensive universities, HSI’s and HBCU’s [iv]), we have identified the following as the most critical levers for starting and maintaining institutional culture change that results in equity gap reductions and better success for all students [v].

1. Data collection, analysis, and use

- How to find available data and use it better, by disaggregating and sharing it broadly and clearly

- Engaging Institutional Research offices as partners.

- Developing Key Performance Indicators on student success and using data to hold the campus community accountable.

2. Effective campus-wide communication and engagement

- Campus-wide training for faculty (including adjuncts) and all non-academic staff (including campus facilities and services staff).

- Communication to entire campus community regarding institutional culture change and equity gap reduction strategies.

- Data on student success and progress are shared with the campus community.

- All faculty and staff are engaged as partners in the goal of institutional culture change and equity gap reduction on their campus.

3. Hiring strategies and personnel policies

- Strategies for more diverse and equitable hiring that consider collective bargaining if needed.

- Importance of empowering a high-level person who leads the charge, has resources to ensure the campus is making progress on equity and diversity goals, has the authority to hold others accountable, and is accountable for meeting campus-level goals.

- Hiring strategies need to promote campus culture change and include activities such as revising job descriptions and interview questions, ensuring diverse search committees and diversifying job posting locations/websites.

- All campus community members are held responsible for student success.

4. Auditing campus and state policies and practices to identify those that perpetuate the status quo

- Identify alignment with institutional culture change and equity gap reduction strategies.

- Evaluate those typical practices that can easily change and those that are mandated by institutional or state policies.

- Work to modify practices and policies as needed.

Knowing what needs to happen does not mean all are ready to take the steps to get there, but we no longer have a choice. The Foundation for Student Success and NCHEMS will continue to work with states and institutions to assure all students have the services they need to be successful.

References

[I] WICHE (2016) available at https://knocking.wiche.edu/

[ii] For Title IV Postsecondary Institutions in the U.S. (50 States including D.C.), 72.1% of all students attend public institutions (NCES, IPEDS 2015-16 Unduplicated Headcount Enrollment File; effy2016 Provisional Release Data File).

[iii] Dennis Jones (NCHEMS) first introduced this concept in a webcast on January 29, 2019. It is available at www.nchems.org.

[iv] Institutions involved in the Foundation for Student Success project are below. The first institution served as mentors with those below it served as mentees.

- CSU –Channel Islands, CA

- Central State University, OH

- Southern CT State University, CT

- Adams State University, CO

- Los Medanos College, CA

- AZ Western College, AZ

- Community College of Aurora, CO

- Yakima Valley Community College, WA

- Rutgers University – Newark, NJ

- Kentucky State University, KY

- Northeastern Illinois University, IL

- Texas Southern University, TX

- San Jacinto College, TX

- Edmonds Community College, WA

- Monroe Community College, NY

- Salt Lake Community College, UT

- Santa Fe College, FL

- Coconino Community College, AZ

- El Paso Community College, TX

- Thomas Nelson Community College, VA

- University of South Florida, FL

- University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV

- New Mexico State University, NM

- Augusta University, GA

- Winston-Salem State University, NC

- Savannah State University, GA

- University of Michigan, Flint, MI

- Langston University, OK

[v] Through the work over the last two years of the Foundation for Student Success (FSS), we have illuminated levers for real institutional culture change. Here is how we did it:

In the fall of 2016, NCHEMS staff used publicly available data sources to identify a small group of community colleges and public universities across the country whose students were being more successful than input variables would predict. The analysis began by including those institutions with at least 25% of the student body coming from the following populations: American Indian, Black, and/or Latinx. The results allowed us to identify institutions that might have some promising practices.

NCHEMS staff interviewed leaders at these institutions. The FSS Board members evaluated the information gathered and identified colleges and universities that had been successful in actually changing the culture on their campuses. These institutions were then invited to become mentors. The result was the selection of seven mentors, each of which agreed to work with three similar institutions over the next two years. We called these groups ‘pods’

NCHEMS staff members managed the logistics for monthly calls for each of the pods. The topics for each of these conference calls were dictated by the mentees. In each pod, the mentor hosted the call and brought in a broad range of people from across their campus to address the mentor campus’ practices around a specific topic (e.g., leadership changes, training across campus, hiring strategies). The mentees and mentor campus staff members then had conversations about suggestions and advice as the mentees figured out how they could adapt their campuses’ practices toward culture change to reduce equity gaps. FSS staff listened and took notes on each call.

Each of the mentor institutions developed a case study. FSS staff also hosted calls among the mentors as they learned from one another what was working in their roles as mentors and what challenges they encountered. In several cases some of the mentee campuses slid off the call schedules. If the mentor was unable to connect with the mentees, the FSS staff would intervene. In all cases the lack of responsiveness on the part of mentees was due to personnel changes.

In the spring of 2018, FSS staff surveyed the faculty and non-academic staff at the mentee campuses to assess how deeply the student success messages were being spread throughout the institution and to measure progress on the goals set for the project by the mentee institution. In addition, each mentee campus submitted a short report on their activities in the project. They also modified their original goals for the project.

Author Perspective: Analyst