Published on

Moving the Clock Forward on Program Design to Drive New Learning and Enrollment Outcomes

Imagine your friend, a professor friend at Big State University, tells you that she’s been asked to create a new program in her department. This new program is in her area of specialization and passion; she plans to attract a new student population the university doesn’t serve well. With excitement, she shares that this program will be the first of its kind in the nation, and maybe in the world.

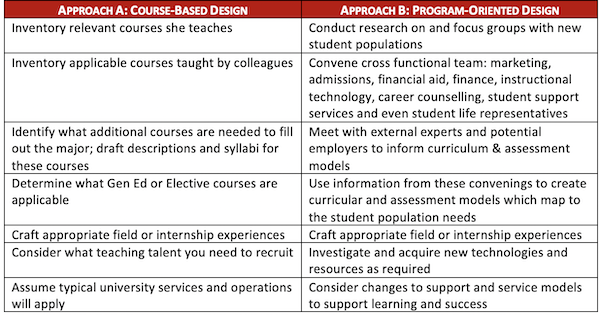

If you ask her how she will go about designing the program, which of these two approaches seems most likely?

Who could blame our fictional faculty member for choosing Response A? Leveraging existing systems and processes “as is” is a viable design decision. However, if you use what you’ve got, you’ll get…well, what you’ve already got.

If you truly want to innovate in a complex organization or system, you must anticipate the ripples innovations will cause across the system. The world of product design has methodologies, tools, and processes to help do exactly that. In fact, one possible definition of design is anticipating and solving problems before they emerge. The difference between a well-designed sofa and a poorly designed one become apparent after sitting in each for a while. In one, problems emerge. In the other, those problems have been anticipated and solved before you sat down.

The business world is embracing a design-centric approach more and more because the numbers back it up. Design Management Institute’s Design Value Index has shown that design-centric companies return approximately 200% over the S&P 500. Companies in the McKinsey Design Index have outsized revenue and return to shareholders due to cost savings and superior user experience.

The benefits of program-oriented design in higher education

As with many models that begin their lives in the corporate world, we have to ask ourselves whether it will work for education. I believe it does. Here’s why:

1. Design Specs

Proper design specs can lead to faster implementation, because key stakeholders have helped to create the plan. Communication improves as a result.

2. Target Learners

A deep, up-front understanding of the target learners and those who teach and support them will lead to greater success for the learners. What’s more, it will also contribute to the success of the program and help it stand out in the marketplace of offerings and ideas.

3. Diverse expertise

Bringing diverse expertise together to establish shared principles ensures less friction and greater collaboration from start to finish. We can anticipate issues and prepare to address them.

Even if our early assumptions are off target, we’ll be able to react more quickly to reality because we have planned, documented, shared and committed to the guiding principles of the program design.

Caveats to consider

We must not allow the design to become a dictator. Iteration must be built in. We should aim for commitment to design principles rather than decisions and opinions strongly held. I’ve heard this called “sufficient design.”

We also need to consider the role of the designer. The label “design-led” sounds too much as though the designer is the privileged leader on the team. This couldn’t be further from the truth. In fact, the designer serves the users of the program, which includes not just learners, but also the faculty, staff, future employers of graduates, and anyone one else touched by the program’s outcomes. Designers are strategic consultants, empathetic listeners, and relentless multi-channel communicators who help bring their team’s design to life.

Picking the right time to leverage a design-centric approach

So, when does this design-centric approach make the most sense for developing new educational programs?

- When context or student populations have shifted, and prior assumptions and models may no longer apply.

- When the audience or user viewpoint is key to the program’s success.

- When the system or organization that needs to embrace the new program is complex.

- When the experience of diverse contributors and experts matter.

There are times when the “as-is” approach to higher education is fine as a foundation for the development and launch of a new program. However, scenarios and contexts which demand innovation or a break with the past are growing and will demand that we anticipate and solve program problems before they emerge. These scenarios and contexts will demand a design-centric approach.

Author Perspective: Administrator