Published on

Declining College Enrollment from Traditional-Age Students Will Hit Hard: Are Adult Students the Answer?

In a new book by Nathan Grawe entitled Demographics and the Demand for Higher Education, the author develops a higher education demand index (HEDI) that looks at the slowing growth in the number of traditional-age students graduating from high school. The author’s unique contribution is to factor in how likely a student is to go to college. His method accounts for the growing number of Hispanic students and their lower likelihood for pursuing higher education.

We know how many students will graduate from the nation’s high schools. The puzzle is how many of those students will go on to college. HEDI attempts to help answer that question.

Grim Outlook for Traditional Admission

The outlook is grim for most of higher education. We will have rising demand until 2025 and the numbers beyond will pose major challenges. Across most of the U.S., we are projected to have 450,000 fewer students in the years beyond 2025. This will mean 25,000 fewer faculty positions.

The areas of the country predicted to grow in population (non-urban Texas and the Mountain West) will produce slightly more high school graduates, but these are areas that have small populations. A rate of growth that appears good will yield very disappointing results.

Elite Colleges

Conversely, the picture looks pretty good for elite colleges. As our economy has become increasingly bifurcated, the number of families earning above $125,000 with both parents having a bachelor’s degree has been growing. These are exactly the families who want to send their children to elite colleges. The outlook for elite colleges looks fairly robust in the South and West and generally less bad in the Midwest and Northeast. This expansion for full-pay and elite admissions is happening at the same time as a severe contraction is coming for college admission across the areas of the United States that have traditionally admitted large numbers: the Northeast, the Mid-Atlantic, and the Midwest.

Declining Enrollment Among Adult Students, But…

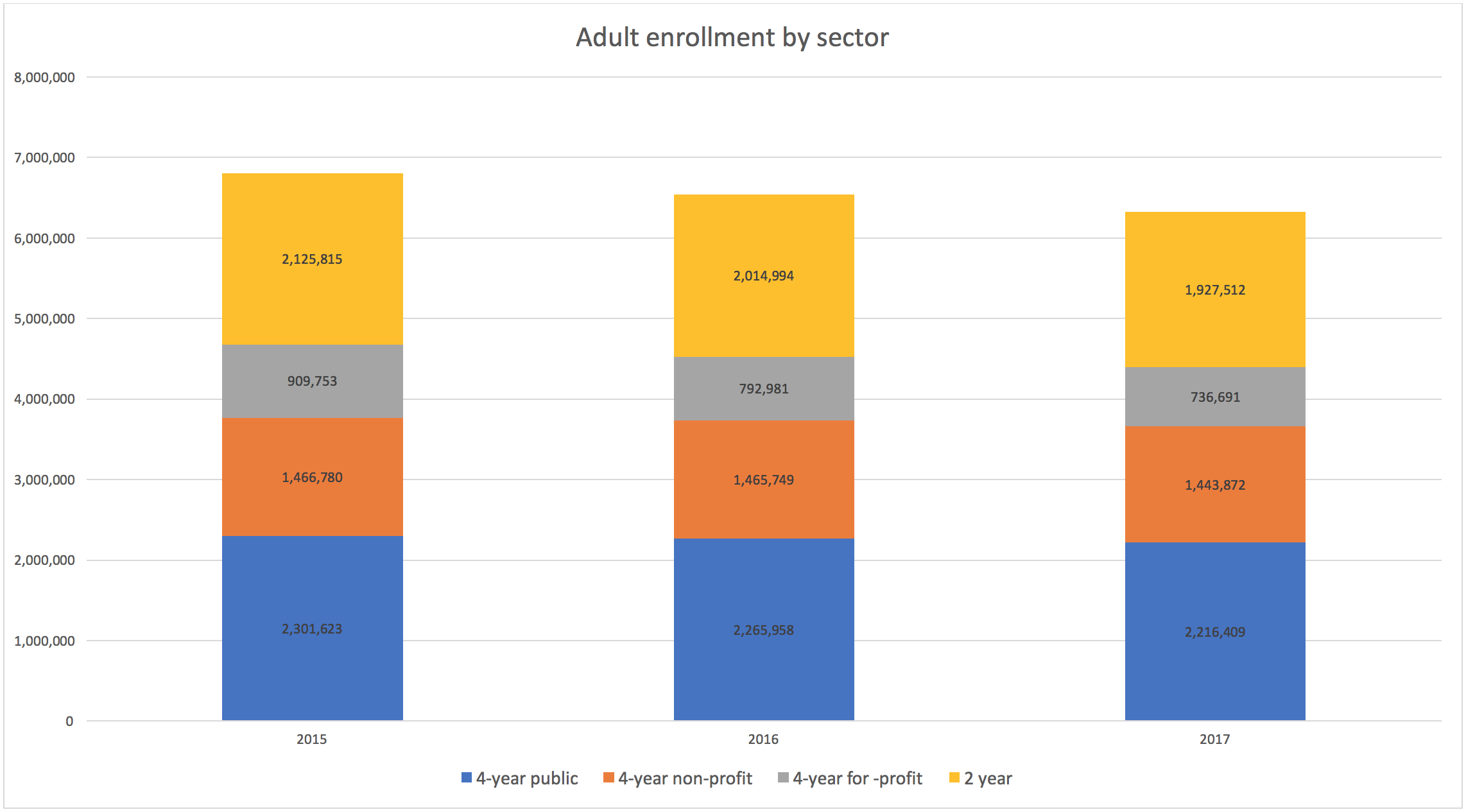

For the last three years, enrollment among adult students nationally has been in decline. The numbers are especially steep for the for-profits and the community colleges, but they are declining in all sectors. This chart presents the enrollment by adults (age 25 and up) for each of the last three fall semesters (2015, 2016, and 2017), according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center (2017).

Enrollment for Online Programs Increasing

Enrollment for Online Programs Increasing

At the same time, enrollment in online programs nationally has been increasing. While the trends are not uniform across institutions, enrollment in purely on-ground programs has declined. There are 1.3 million fewer students in solely face-to-face programs in 2016 as compared to 2012. In 2016, 673,000 more students enrolled exclusively online compared to 2012, and 580,000 more were enrolled in at least some online courses.

This reflects the development of robust online programs in some non-profit and public 4-year institutions, as well as at some community colleges.

Thus, we have declines in face-to-face enrollment from adult students coupled with a good rate of growth in online programs. These seemingly contradictory trends are worth noting. It appears that enrollment for adult-focused online programs has been growing and the enrollment for the purely face-to-face programs that serve adults has been shrinking.

The Bright Outlook for Adult Students

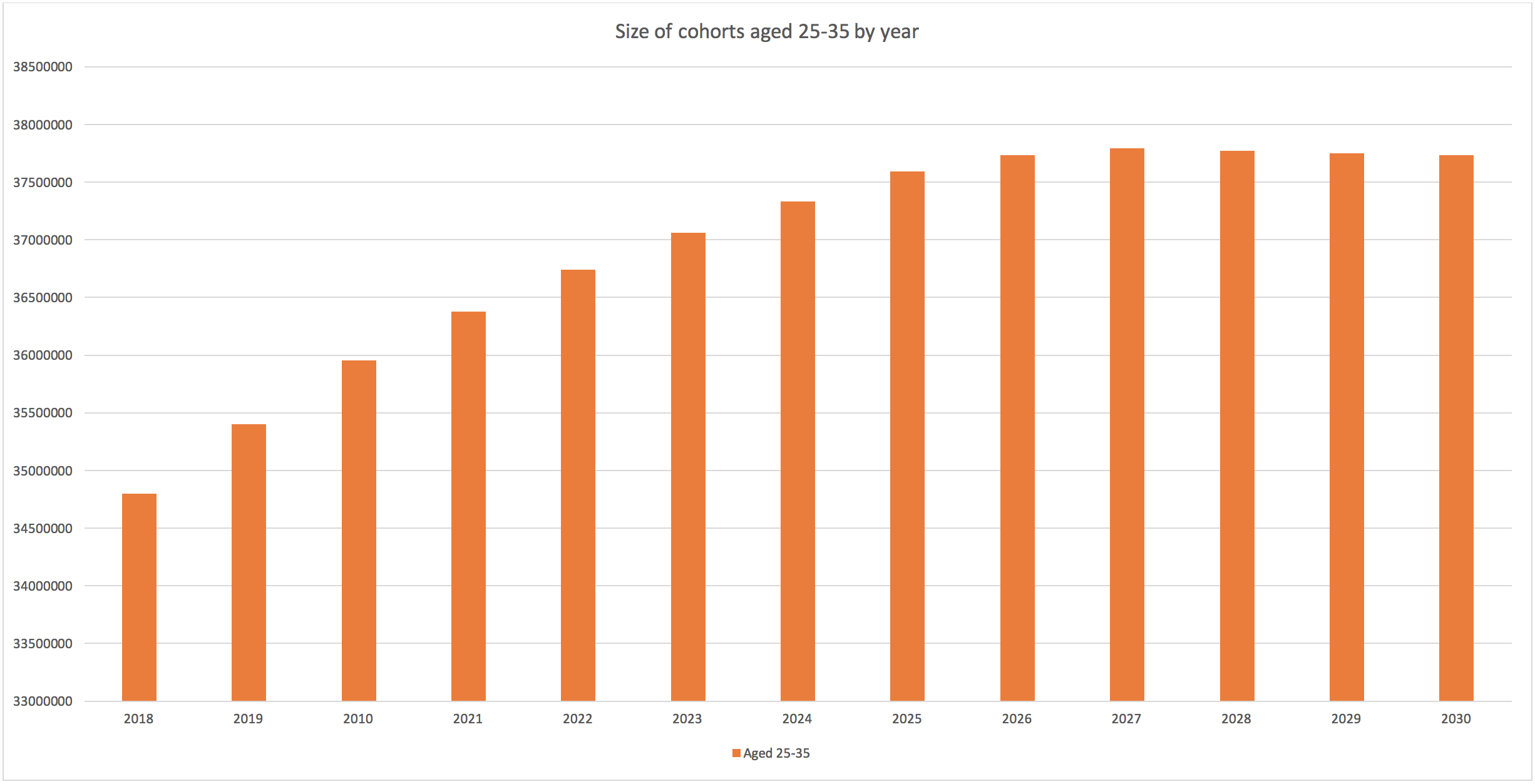

The size of the group aged 25 to 35 who graduated from high school is projected to climb steadily through 2030. Using data from the 2016 report Knocking at the College Door from WICHE, we will have more people in this age range in 2027 than in any recent time, a rise to nearly 38 million or an increase of nearly 3 million from the size of that group today.

While we don’t know how many will have gone to college and then dropped out (the key criterion for degree completion), the sheer size of the change is hard to belie. We can expect an increase in enrollment for adult students in the coming years. This is consistent with the analysis from the U.S. Department of Education, which predicted in 2017 a rising number of adult students in the near future.

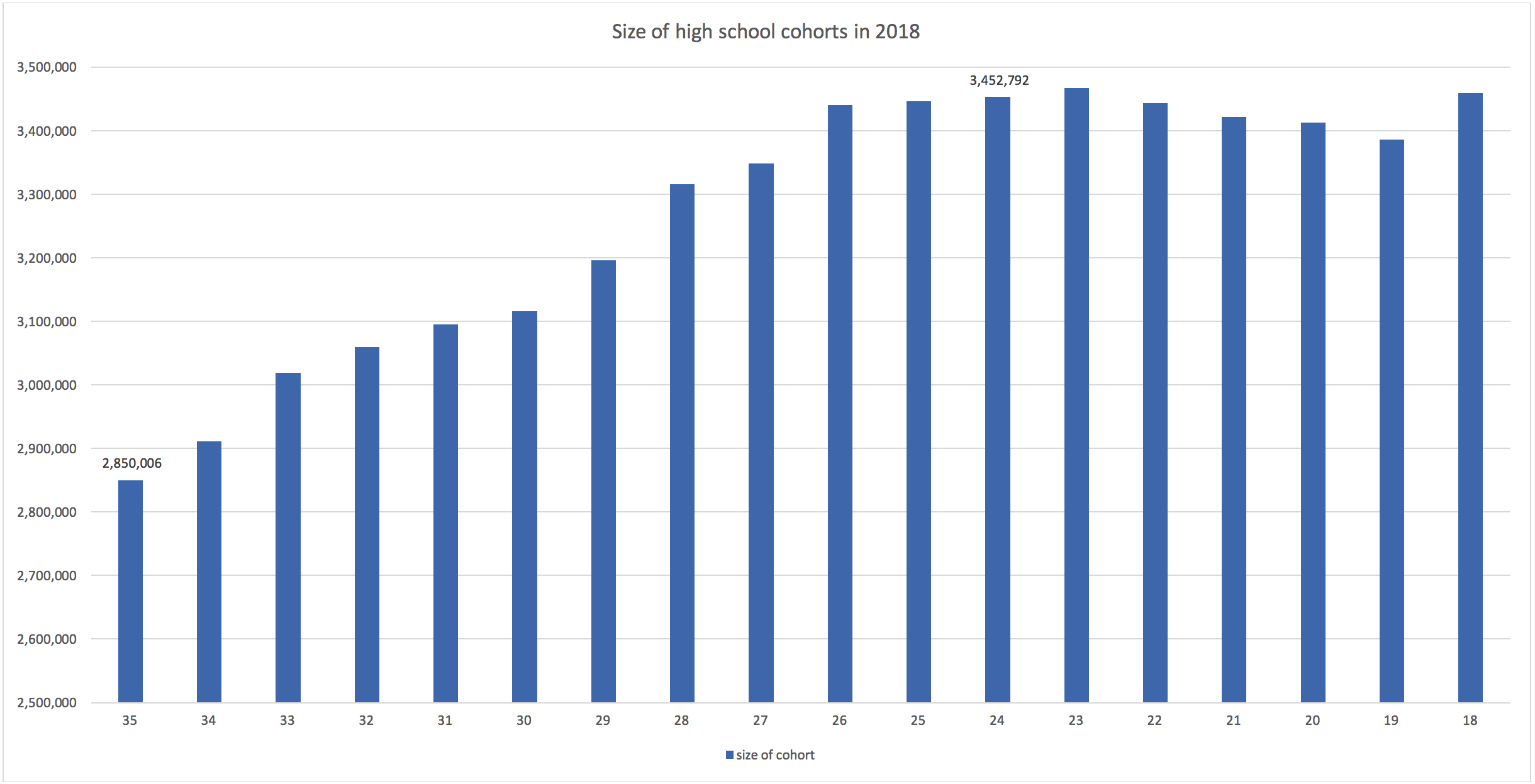

The prime years for adult students to return to college are from ages 25 to 35. To gain some understanding of how many adult students will enroll, we have to look back at how many graduated from high school in years past. The way to think about this is, “How many students will have dropped out of college after first entry 6 to 7 years ago?” That stop-out group is the target market for adult-centered programs.

In the accompanying chart, the number of high school graduates was at a low point in 2000. That means the oldest segment (age 35 today) of the adult student market is relatively small. Only 2.85 million graduates from 2000-2001 were recorded. The more recent cohorts look a bit better. In 2010 (our key year of focus) 3.45 million high school graduates were logged, or a growth of nearly 600,000. This trend for fairly large high school classes that are now ages 25-35 will continue through 2030. Thus, we can expect growth in the number of adult students in college in the years ahead. These weaker trends in the older portion of the cohorts help us to understand why the most recent years have been soft.

For another view of this, we add the size of the high school graduating classes that are currently aged 25 to 35 (the key ages for adult-centered programs) and project those forward:

For another view of this, we add the size of the high school graduating classes that are currently aged 25 to 35 (the key ages for adult-centered programs) and project those forward:

This shows a rosy future for enrollment in adult learning programs, peaking in 2027 and maintaining a mostly steady state through 2030. Thus, we can be buoyed by the demographic trends ahead.

This shows a rosy future for enrollment in adult learning programs, peaking in 2027 and maintaining a mostly steady state through 2030. Thus, we can be buoyed by the demographic trends ahead.

However, we need to remember these words from a study by the National Academy on an Aging Society in 1999: “Demography is not destiny.” A number of other factors may alter these trends.

- The advantage that a college degree gives a candidate in the job market is sizable and is expected to grow. This provides adult students with an incentive to complete their undergraduate degrees.

- Conversely, an improving economy has a negative effect on community college enrollment by adult students. Stronger job markets seem to make community college less desirable.

- Since 2004, there is a rising share of students going to college out of each of these cohorts. More are going to college, but are they finishing?

- The continuing trend is for very low completions at community colleges and for-profits, which may mean more opportunity for adult degree completion at the 4-year public and private institutions as students drop out and return later in life.

- There is an increasing amount of distrust of higher education by Republicans, which will probably mean challenges in financing. It is possible that public support for higher education will decline. We’ve seen this in Illinois with reductions in the funding of the Monetary Assistance Program and declining support for our public institutions.

- The trend toward microcredentialing may hinder the market for completion of both bachelor’s degrees and graduate degrees. Most micro-credentialing has happened at the graduate level, so it is unclear what impact this trend will have on degree completion.

- Perhaps the most important trend will be the ways in which artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics affect the job market. How will we re-train truck drivers and cabbies in the age of driverless cars? How will a host of other professions be affected? Adult learning’s role in re-training or re-tooling may mean a period of further rising opportunity.

It is clear that making a commitment to serve adult students via online and blended learning will produce good results as we ride the rising demographic wave that occurs within the next few years. It will be incumbent for our programs to connect with the career aspirations of our students and document our career outcomes to convey those in marketing for prospective students. Adult learning programs are largely disconnected from the controversies that have plagued many elite institutions in recent years. We will need to convey the focus of adult-centered institutions on applied degree programs to overcome distrust. Since relatively few community college students who are adults finish at the community college, a continuing focus on degree completion, separate and distinct from community college partnerships, is likely to produce good results.

The grim forecast that comes to us from Nathan Grawe’s HEDI presents a difficult future for traditional higher education—the part of our profession that focuses on the 18- to 22-year-old demographic. With the exception of elite colleges, we can expect large challenges in that arena. A brighter future is in store for adult-centered programs, particularly those that are available online. Adult programs from institutions that truly embrace adult learners will thrive in the years ahead.

– – – – References

Fong, J, Janzow, P., Peck, K. 2016. Demographic Shifts in Educational Demand and the Rise of Alternative Credentials. UPCEA. Retrieved from https://upcea.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Demographic-Shifts-in-Educational-Demand-and-the-Rise-of-Alternative-Credentials.pdf.

Grawe, N. 2017. Demographics and the Demand for Higher Education. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

Lederman, D. 2018. Who is Studying Online (and Where). Inside Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2018/01/05/new-us-data-show-continued-growth-college-students-studying.

National Center for Education Statistics. 2017. Digest of Education Statistics. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d15/tables/dt15_303.40.asp.

National Information Center for Higher Education Policymaking and Analysis. 2018. College-Going Rates of High School Graduates – Directly from High School. Retrieved from http://www.higheredinfo.org/dbrowser/?year=2004&level=nation&mode=map&state=0&submeasure=63.

National Student Research Clearinghouse. 2017. Completing College: A National View of Student Completion Rates – Fall 2011 Cohort. Retrieved from https://nscresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/SignatureReport14_Final.pdf.

National Student Research Clearinghouse. 2017. Current Term Enrollment Estimates – Fall 2017. Retrieved from https://nscresearchcenter.org/current-term-enrollment-estimates-fall-2017/.

Pearson, W. 2017. The College Wage Premium is Very Large. LinkedIn. Retrieved from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/college-wage-premium-very-large-walter-pearson/.

Pew Research Center. 2017. Sharp Partisan Divisions in Views of National Institutions. Retrieved from http://www.people-press.org/2017/07/10/sharp-partisan-divisions-in-views-of-national-institutions/.

Smith, A. 2015. Enrollments Fall. Inside Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2015/05/14/improved-economy-leads-enrollment-dips-among-two-year-and-profit-colleges.

Western Interstate Commission on Higher Education. 2016. Knocking at the College Door. Retrieved from https://knocking.wiche.edu/data.

Author Perspective: Administrator