Published on

Three Ways to Improve Online Student Retention and Graduation Rates

Higher ed institutions are obligated to retain the students they have just as much as (if not more than) recruiting new ones. By engaging their students, providing credit for prior learning and ensuring flexibility, institutions can ensure their students return to them.

COVID-19 brought in-person learning to a screeching halt while pushing online learning into all corners of education in 2020. If you pursued any post-secondary education after March 2020, chances are it was delivered online. You may have seen the flurry of pride that institutions shared on social media and in official COVID announcements about translating all courses into online delivery in as little as two weeks. The optimism was contagious, and many U.S. faculty members jumped head-first into their inaugural term of online teaching.

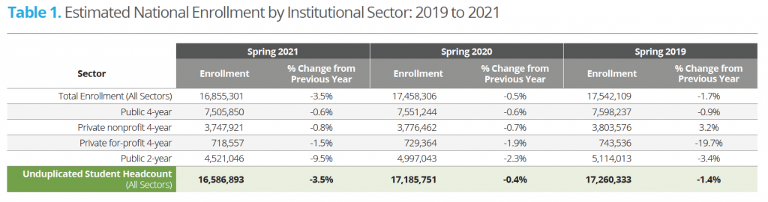

The stakes for post-secondary enrollment haven’t been this high in a decade. National Student Clearinghouse reported that in Spring 2021, undergraduate student populations decreased by 4.9% YOY (727,120 enrollments) across all institution types while graduate student populations increased by 4.6% YOY (124,115 enrollments). Spring 2021 enrollment results illustrate decreases among all institution types, with community colleges hit the hardest:

- Public four-year (.6% decrease, loss of 45,394 students)

- Private nonprofit four-year (.8% decrease, loss of 28,541 students)

- Private for-profit four-year (1.5% decrease, loss of 10,807 students)

- Public two-year (9.5% decrease, loss of 475,997 students)

Since eLearning is not only here to stay but also growing each year, online student outcomes are essential to institution sustainability. Unfortunately, online student retention is historically lower than traditional student retention. One study estimates online student completion rates to be 8-14% lower than in-person courses (Xu & Jaggars, 2011a, 2011b), while another concluded online course completion is 10-20% lower than in-person completion (Moore & Fetzner, 2009). Moore and Fetzner (2009) also calculated that the graduation rate for online undergraduate degree programs is only 56%.

This article briefly reviews three intervention categories that optimize online student retention and graduation. Full-time or part-time enrollment status, Credit for Prior Learning (CPL, aka Prior Learning Assessment) and human connection opportunities will be explored for you to decide what will best serve your online student population.

Full-time vs. Part-time Enrollment Status

Complete College America and the Lumina Foundation conducted a longitudinal study (2011) including 33 states enrolling over 10 million students, and they found that only a quarter of part-time students graduate, even when given twice as long to complete. On a smaller scale, my dissertation on Drexel Online’s new enrollments (2014) found that with a population of 2,753 new online students, enrolling in two or three courses for their first term as opposed to enrolling in one course positively affected persistence both in the second and third terms. Encouraging students to take additional courses may yield higher persistence, especially in their first year.

The first step is to determine if students have the capacity to take additional courses. For those who do, provide course options that are well-rounded in qualitative and quantitative balance to maximize their success potential. Since the first year of enrollment is where most attrition occurs, plan a full year of program mapping for both part-time and full-time scenarios. For administrators, plan one year ahead in course schedules and faculty assignments. Through careful planning and providing multiple scenarios, part-time students may opt to accelerate their program and therefore improve their odds of graduating.

Credit for Prior Learning (CPL, aka Prior Learning Assessment)

The Council for Adult & Experiential Learning (CAEL) conducted two longitudinal studies measuring the effects of CPL on retention and graduation rates. Their findings in both studies (2010, 2020) are valuable when considering retention and graduation objectives. In their 2010 study (n=62,475 adult students from 48 institutions), CAEL found that CPL students had higher persistence and graduation rates than non-CPL adult students. Many CPL students also needed less time to complete a degree, depending on how many CPL credits were earned. In their 2020 study, CAEL found that 49% of CPL students completed bachelor’s degrees, associate degrees and certificates, compared to 27% of non-CPL students throughout the same 7.5-year time period (n=232,622 adult students from 69 institutions). Offering Credit for Prior Learning may increase retention and graduation rates for adult students (25+ years old).

There are many forms of CPL your institution can offer students, including:

- Standardized exams (e.g., College Board CLEP exams, DSST military exams through Prometric, UExcel exams through Excelsior College)

- Challenge or departmental exams

- Portfolio assessment

- Credit for military training (through American Council on Education)

- Credit for corporate or external training (typically through ACE or National College Credit Recommendation Service credit recommendations)

- Institutional review of external certifications, licenses or training

As with any retention tool, accessibility and awareness are critical for students to pursue CPL. If your institution already offers CPL, informing students as early as possible (i.e. during orientation) can help them map their pathway to graduation. While CPL fees vary and are often lower than standard tuition, the increases in retention and graduation rates will typically outweigh any earlier revenue loss.

Human Connections

Online learning is not for everyone, so creating an environment where students significantly engage with others may positively affect retention and graduation. The demand for online student coaching beyond academic advising has created organizations like Inside Track. Their model while partnering with Drexel University Online (2012-2013) included coaching on academic performance; family, school and work balance; personal finances; time management; effectiveness and follow-through; health and wellness; commitment to graduation; and career planning. Through A-B testing with undergraduate degree-seeking students during the first two terms, the group of students coached by Inside Track had a four-point lift in both second- and third-term persistence (Delleville, 2014).

Hiring external coaches to work in tandem with academic advising can be a powerful tool for student engagement. Another option is to provide formal training on online education coaching to student-facing advisors. Evaluating human connection interventions will shed light on what may already be working best for your students. Do students in a cohort model (pursuing their program with the same core group of students) persist at higher rates than those without a cohort? Do students who work with certain faculty members or advisors have higher retention rates? How can your institution reward these positive outcomes? Measuring such factors will provide the answers needed to customize your institution’s online student retention strategy.

Summary

Online student retention is a result of many student experiences, and some are more easily identified than others. As with any business model, it will always be less costly to retain students than to recruit new ones. Through evaluating the data and adapting as needed, any institution can prepare online students for graduation and future alumni success stories.

References

Complete College America (2011). Time is the Enemy. Indianapolis, IN.

Moore, J. C., & Fetzner, M. J. (2009). The road to retention: A closer look at institutions that achieve high course completion rate. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 13(3), 3–22.

National Student Clearinghouse. “Current Term Enrollment Estimates.” June 10, 2021.

Xu, D., & Jaggars, S. S. (2011a). Online and hybrid course enrollment and performance in Washington State Community and Technical Colleges. Report of Columbia University, Working paper no. 31, 1–37.

Disclaimer: Embedded links in articles don’t represent author endorsement, but aim to provide readers with additional context and service.