Published on

Making the Most of Limited Time: How to Improve Persistence Rates of Part-Time Students

As a result of higher education’s push to improve accessibility, a broader and more diverse student population is enrolling than ever before. Rather than fully committed 18-year-olds fresh out of high school and ready for an intensive residential experience, today’s learners are non-traditional: they are balancing their educational goals with family and work responsibilities. As such, many are enrolling in higher education part-time, and colleges and universities have a new responsibility to build engagement models designed for this population. In this interview, Christina Hubbard shares her thoughts on some of the most significant roadblocks to completion facing part-time students, and reflects on a few strategies and tactics institutions can put into place to help them overcome those obstacles.

The EvoLLLution (Evo): Why is it so important for colleges and universities to focus on improving persistence for part-time students?

Christina Hubbard (CH): Part-time students comprise the majority of community college enrollment, and are no small percentage of enrollment in four-year colleges. In fact, 83 percent of community college students will enroll in part-time education at some point, yet they fare far worse than their full-time peers. We wouldn’t accept the current rates of part-time success among any other student population without aggressively trying to improve them, and I feel part-time students should be more urgently supported.

In my experience, most part-time students would attend at greater rates if they were able, but the reality is that many are raising children and/or balancing work to afford college education. At the same time, the majority of today’s jobs that pay a family-sustaining wage demand a college education, so there is a real need to ensure college success can be achievable for these students as well.

It’s also important to point out that part-time students are increasingly younger than they have been in the past. Many colleges assume that part-time students are older, working adults who don’t have completion goals. In fact, a growing number (29 percent as of 2015) are 18 to 21 years old, and are balancing multiple jobs and family responsibilities.

So, overcoming the information gap is the first step to bridging the service gap.

Evo: Where are some of the biggest gaps today between how postsecondary institutions serve part-time learners and what those learners need?

CH: While significant strides have been made to adapt college structures to better serve part-time learners, there is still much work to be done. Our research suggests that shorter terms tend to be more effective for students, and they accommodate the changing demands on the lives of part-time learners—yet most colleges still work on a 16-week semester or a 10-week quarter. This means that there are exponentially more chances of a part-time student’s busy life getting in the way of college success. For example, if a student encounters an insurmountable barrier in week 12 of a regular semester and has to drop out, they’ve lost all of the credits for which they’d enrolled. However, if they had enrolled in two eight-week terms, they’d still have the successful credits from the first eight-week term to support their academic progress. I have seen countless instances where military members were unexpectedly sent on temporary duty or parents were forced to withdraw from the remainder of the term due to a family member’s illness. By shortening terms, institutions can provide more opportunities for these students to make progress.

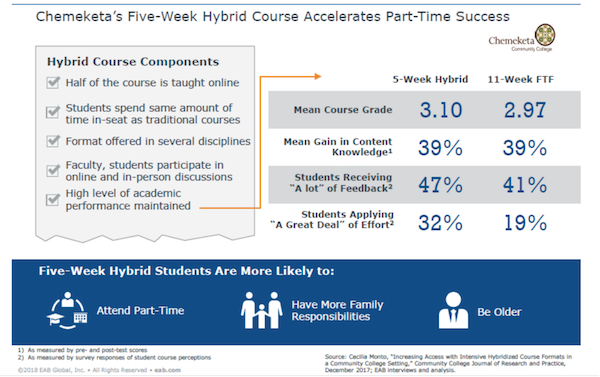

That said, I have heard countless arguments about the pressure that shortened terms put on part-time students. Cutting a term in half demands twice as much time in seat per week. However, the data shows that shorter terms often yield better course pass rates. This means there’s a great opportunity to use technology to support learners. For example, hybrid courses are an excellent way to increase class time without requiring students to take a trip to campus. I’ve seen some particularly innovative practices in this regard; for example, when Chemeketa Community College sought to convert courses that had previously been taught face-to-face over eleven weeks into five-week hybrid courses, they wanted to ensure they maintained their high standards.

Another college actually set up its college success skills class as a hybrid course, but students had to demonstrate their ability to thrive before independently accessing online content. The instructor would show up to class each week, and based on the students’ work and progress, they would be allowed to complete the rest of their coursework online. So, if the course were a Monday/Wednesday class, all students would attend every Monday throughout the term. They were expected to be in class Wednesdays until they demonstrated that they understood how to do the online assignments and were able to consistently complete their work. This also provided a fantastic training ground to empower students to feel more confident about their ability to succeed in online classes, so they could consider using them to fulfill future degree requirements.

I think many of us are beginning to question the fundamentals of our higher education structure. For example, why does time in seat take greater precedence in learning than demonstrated mastery of content? Students can access information through a variety of sources today, so why would we ask students who have had significant exposure to information to spend as much time on a topic as those who are novices? Instead, an honest assessment of students’ understanding of content—especially if it included real-world application of the material—would serve today’s students far better. Obviously, we need to maintain our high standards for education, but we have seen a number of methods for student assessment that can also demonstrate how that content can be applied in a workplace setting.

Recently, the Center for American Progress released a report highlighting some innovative ways that institutions are supporting part-time student success—most notably by giving them opportunities to experience the campus culture that, as non-traditional learners, they far too often miss out on. For example, students enrolled in Bunker Hill Community College’s learning communities are seeing significant gains in persistence rates. The college’s findings are consistent with my own research that indicates part-time adult learners seek connection to other students like them, as well as faculty and staff; yet, our existing structures too often limit opportunities for part-time students to connect. Reimagining some of these foundations of higher education can serve part-time students very effectively.

Financial aid is also a major impediment to part-time student success. First of all, today’s Pell grants have far less buying power than they had a generation ago. This compels our low-income students to work while attending college at rates far higher than they’ve needed to in the past, which, in turn, puts more pressure on the precarious balance they need to maintain between academic, personal and professional responsibilities. Sara Goldrick-Rab provides an in-depth explanation of the buying power of today’s Pell grant as compared to those of previous generations in her book Paying the Price. This decreased buying power is a major disadvantage to our students. Without increased financial aid, students are forced to work longer hours, which reduces their enrollment levels and leads to longer time-to-degree—as well as greater chances of getting derailed from successful completion.

There are also several misconceptions about financial aid eligibility for part-time students that may keep students from applying. In my work as a director of a college access and success program at Northern Virginia Community College, we saw countless adult students who had been told they were ineligible for aid due to their age or the fact that they weren’t attending full-time. Countering these misconceptions may provide an opportunity for students to increase their rates of enrollment.

Evo: What are a few steps colleges and universities should take to improve their support of part-time learners?

CH: The practices coming out of Bunker Hill are promising and can be scaled to other college environments. That said, I believe there is a lot of low-hanging fruit for supporting part-time learners. This year, EAB’s Community College Executive Forum conducted an intensive study on building greater success among part-time students, and our members have been thrilled to see us take on this challenge.

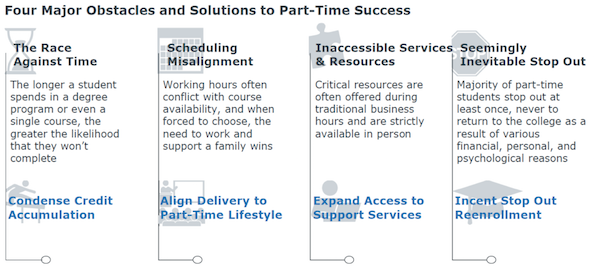

We found that challenges facing part-time students fell into four main categories that we tackled in our research:

We identified a number of fantastic approaches that can be scaled. First, credit accumulation can be condensed through accelerated coursework or staggered course starts. Second, course delivery can be aligned to the lives of part-time students by offering block schedules and more weekend classes. Third, part-time students should have comparable access to services as full-time students. This may require virtual services or bringing support staff to students on campus.

Finally, re-enrollment among students who have previously stopped-out should be incentivized. The majority of students who stop-out do so because they need to work more. With campus and curricular changes to better support students, there is a massive opportunity to reengage those students who didn’t believe they could finish under the former structures.

Evo: What roadblocks would you expect leaders to encounter in trying to implement these kinds of approaches on their own campuses, and how would you recommend they try to approach or overcome them?

CH: Changing course schedules, asking for faculty flexibility to accommodate best practices for part-time students, and offering the support services students need would go a long way, but funding is always a concern. Culture shift often incurs expenses; however, colleges with high rates of part-time enrollment have little choice but to better serve these students. With anticipated full-time enrollment declining across all sectors and a greater need for higher education to lead to family-sustaining wages, the time to introduce new approaches is now. What most colleges need are tried and true practices that can be scaled, so that they aren’t spending money on ineffective efforts. I believe one of the best things higher education administrators can do is to share the practices that are serving part-time students effectively.

Author Perspective: Association