Published on

Microinvalidation: Microaggression’s Ugly Cousin

As a project team manager, I had the opportunity to be part of a larger project team that was implementing a new service across the entire organization. Given the amount of work to be done, I recognized the need to hire additional team members. Per our organizational policies, I created descriptions of the roles I needed to fill. Being sensitive to our virtually non-existent budget, I coded the positions as part-time and temporary. I submitted the positions and began planning how my increased team would operate. But instead of posting my positions online and opening the recruitment process, I found myself caught in a series of conversations with management, explaining why I needed to hire additional team members. The end of each meeting concluded by scheduling a “follow-up” meeting to continue asking why I needed to hire.

Unbeknownst to me, my colleagues had put together similar proposals to hire additional team members. As I listened to them pitch their ideas, I couldn’t help but wonder how they would each respond to the same barrage of questions I received, because their pitches were nowhere near the level of mine. But, to my shock and concern, those questions never came. Instead, their pitches were approved on the spot.

This left me perplexed. Why were my ideas questioned while those of my colleagues ideas were accepted without challenge? Could it be the departmental budget? The criticality of the roles needed? The ask itself? I just knew there had to be something different about my pitch that kept me from getting the green light my colleagues received. My ideas represented a fraction of the budget compared to those of my colleagues. My idea would support and sustain critical organizational systems. I created detailed job descriptions that were web-ready—my colleagues did not. And perhaps most importantly, hiring would greatly improve our collective work-life balance and mental health, but none of that seemed to make a difference. I approached my leadership to make sense of my perceived disparity of treatment and was told that my ask “did not make sense” and warranted “more discussion to understand.” Rather than further pursuing the issue, I just decided to drop it altogether.

As I started to process this experience, I began to feel angry, humiliated and anxious about the potential for increased workload. I recognized that in this situation (and many others), despite my 20 years of experience working on such projects, despite being a keynote speaker at national conferences, despite being on podcasts in recognition of my place within my industry, despite being a published author on the subject, none of that made a difference.

What I was experiencing is what Mary-Frances Winter describes in her book, “Black Fatigue: How Racism Erodes Mind, Body, and Spirit”—the fatigue that comes from not being believed. My words do not matter until I jump through all the hoops put in my path, and even then they may still not matter unless the result is of some benefit to those with power. I can’t say, “The building is on fire” without being questioned about how I know it’s on fire, whether it can be verified independently, and what gives me the authority to say so.

Winters explains, “These experiences are trauma-inducing and affect Black employees’ ability to do their best work. Constantly being on guard and questioning yourself about how to respond to inequities is fatiguing.”

While these experiences can be jarring and demoralizing for anyone, women and employees of color are affected by them more frequently than anyone—and the impact can be devastating. The feeling that there is some deficiency in oneself usually leads to all sorts of social and emotional issues, including imposter syndrome. For those who are the only woman or person of color in these conversations, these situations can be isolating, and the contributions that can be made are often diminished. Or, worse yet, as Winters expounds, “These Black [brown and women] employees remain silent for fear of being labeled as overly sensitive, not being believed—or even losing their jobs.” When voices are silenced or have little impact, the entire organization suffers. But perhaps the most destructive effect on Black and Brown employees and women, is the lack of trust. In other words, the employee is not afforded the same domain and persona respect as their peers—making them feel “less than” in all respects.

Those of us in management or leadership positions should be aware of which voices we hear, which voices we listen to and which voices matter. We should be aware of the potential for the marginalization of women and employees of color when we do not take their experiences, knowledge and skills into account when solving problems and making decisions. We need to understand how microinvalidations adversely impact our employees. As Columbia University psychologist, Dr. Derald Wing Sue says,

“Microinvalidations: Communications that subtly exclude, negate or nullify the thoughts, feelings or experiential reality of a person of color.”

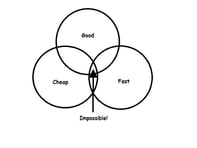

Dr. Sue further explains that microinvalidiations are less obvious [in] nature, which puts people of color in a psychological bind. He asserts, “While the person may feel insulted, she is not sure exactly why, and the perpetrator doesn’t acknowledge that anything has happened because he is not aware he has been offensive. The person of color is caught in a Catch-22: if she confronts the perpetrator, the perpetrator will deny it”. In turn, that leaves the person of color to question what actually happened. The result is confusion, anger and an overall sapping of energy. As managers and leaders, we must recognize that microinvalidations are a daily occurrence for women and employees of color.

As leaders, we should challenge ourselves and one another to create inclusive environments, not just for race and gender but also for thought. Women and people of color need to know that their voice matters. Acknowledging that the fatigue is real and that navigating these spaces can oftentimes seem bleak, the social and emotional well-being of our marginalized employees should never take a back seat to making change in our organizations.

Disclaimer: Embedded links in articles don’t represent author endorsement, but aim to provide readers with additional context and service.

Author Perspective: Administrator