Published on

Defining, Modeling and Communicating a Military/Veteran-Friendly Approach to Success

Our students, faculty, staff and community partners often ask us what the term “Military/Veteran-Friendly” means.

The criteria that frame this term are generally extracted from a variety of sources to include the Department of Education’s Eight Keys to Veterans Success and the American Council on Education’s Toolkit for Veteran Friendly Institutions. These criteria are, in turn, reinforced through a variety of publications that rank schools based on their own proprietary algorithms.

This year over 2,000 institutions of higher education have affirmed their commitment to the Eight Keys, 1,400 schools were recognized as Military-Friendly, and 175 as Best for Veterans. Yet for many, the concept of Military/Veteran-Friendly (MVF) is simply captured in a symbol they have come to trust, but may not fully understand.

The purpose of this short essay is not to advocate for, nor deconstruct, such symbols. Instead, this piece aims to translate how the concepts that underpin our understanding of MVF institutions are sourced, modeled and communicated into meaningful actions that positively shape the student veteran experience at the University of Georgia (UGA). As the director of UGA’s Student Veterans Resource Center my focus is ensuring that our approach to “friendliness” is supported by a coherent architecture that reinforces values, behaviors and outcomes, which through good practice we recognize as catalysts to success.

But why are such catalysts even required? Research authored by the Veterans Administration suggests that, nationally, less than 50 percent of student veterans graduate from college and those that do take up to two years longer than the traditional student.[1] Despite the benefits provided by the Post-9/11 GI Bill, “today’s student veterans are at a higher risk of not graduating than any other racial or ethnic minority group.”[2] As such, any discussion of MVF criteria must start with an understanding of the challenges to success and the outcomes we use to define success.

At UGA, our student veterans represent nearly 85 percent of our defined military-affiliated population (e.g. Active Duty, Reserve, National Guard and Student Veterans). As non-traditional students, veterans face a myriad of challenges to their success that include:

- More likely to be first-generation;

- More likely to pursue a path of self-reliance;

- Less likely to participate in co-curricular activities;

- More likely to have responsibilities outside the classroom.[3]

Research from Syracuse University’s Institute for Veterans and Military Families further informs us of the systemic problems (e.g. lack of financial resources, family obligations and the expiration of benefits) that hinder a veterans’ pursuit of education.[4] These issues are of particular interest at UGA where the overwhelming majority of our undergraduate student veterans are transfer students, average age of 28, who are enrolled in any one of our over 175 academic programs.

To mitigate such risks, colleges and universities have established a variety of military-affiliated offices, many of which are recognized as being MVF. Though these offices offer powerful symbolism that attracts prospective students, they may lack a coherent system of MVF-related strategies needed to effectively bridge the complex challenges facing student veterans. Confounding the situation, each of the nation’s institutions of higher education operate in a unique academic and environmental space and serve a student demographic distinctly shaped by that space. This suggests the MVF strategies designed for one school may not work for other schools, which may have with their own unique cultures and associated veteran populations.

In considering the attributes associated with MVF institutions, a general framework is suggested by the Eight Keys to Veterans Success:

1. Create a culture of trust and connectedness across the campus community to promote well-being and success

2. Ensure consistent and sustained support from campus leadership.

3. Implement an early-alert system to ensure all veterans receive academic, career and financial advice before challenges become overwhelming.

4. Coordinate and centralize campus efforts for veterans, together with the creation of a designated space for them.

5. Collaborate with local communities and organizations, including government agencies, to align and coordinate various services for veterans.

6. Utilize a uniform set of data tools to collect and track information on veterans, including demographics, retention and degree completion.

7. Provide comprehensive professional development for faculty and staff on issues and challenges unique to veterans.

8. Develop systems that ensure sustainability of effective practices for veterans.[5]

Armed with the eight keys, the ACE Toolkit, best-practice data from regional schools with top-rated veterans programs (like Florida State University and the University of South Florida) and a desire to create a positive learning environment at UGA for our veterans, in Fall 2013 the Office of the Dean of Students created a Student Veterans Resource Center (SVRC). Today, the SVRC serves at the nexus of UGA’s approach to serving student veterans. The essence of our approach is captured and communicated through a holistic model.

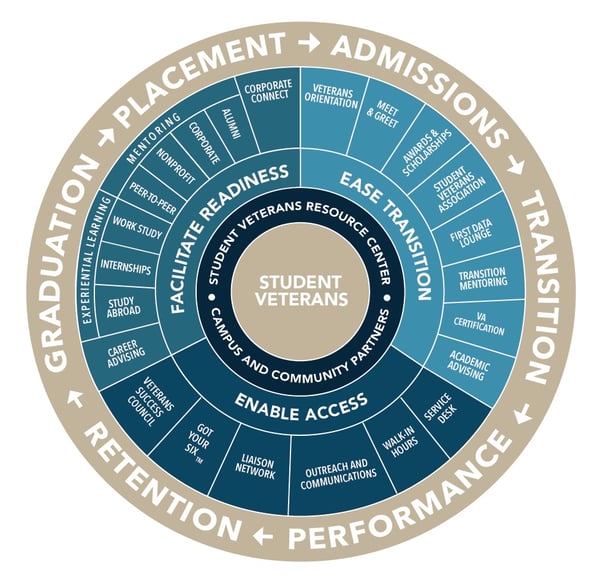

Organized around three goals (e.g. Ease Transition, Enable Access, Facilitate Readiness), 18 target areas and six outcomes, our operating model helps to focus, communicate and optimize our efforts on the most pressing needs of our military-affiliated population. At a glance, the model also helps our students, faculty, staff and community partners understand our emphasis areas and what outcomes we anticipate influencing through our limited resources. Leveraging those resources through partnerships, the SVRC conducts, refers to service providers or encourages participation in each of the targeted areas that we recognize as catalysts to success.

Does this approach yield the anticipated MVF outcomes? As we end our third year the data suggests that, in the aggregate, our student veterans transition, perform, persist and graduate at levels that nearly equal the overall UGA population. Are the results attributable to good MVF practices or because as a Tier 1 research university we attract some of most resilient veterans in the nation? As the model highlights, our strategies are designed around our students; the two are inextricably connected.

In the end, though there are hundreds of other institutions that may enroll more veterans and dozens that may offer wider/deeper MVF-related offerings, we are confident that within the context of our historic land- and sea-grant university, our holistic approach is helping to model meaningful pathways to success.

Whatever your institutions priorities are in terms of programming, you can create a model that aligns your students’ needs with good MVF practice and your institutional capabilities. UGA’s agile model represents a work in progress that may make you rethink your strategy to serving your institution’s military-affiliated population and, as importantly, how you communicate that strategy to your students and stakeholders.

– – – –

References

[1] Veterans Administration Economic Opportunity Report, September 2015

[2] Preparing Your Campus for Veterans Success, An Integrated Approach to Facilitating the Transition and Persistence of Our Military Students, Kelly, Smith and Fox, Stylus Publishing, 2013

[3] American Council on Education, Student Veteran and Service Member Engagement in University Life, December 2013

[4] Syracuse University Institute for Veterans and Military Families, Missing Perspectives, November 2015

[5] Department of Education, Eight Keys To Veterans Success