Published on

Reducing Transactional Distance: Engaging Online Students in Higher Education

Compared to its face-to-face counterpart, online learning provides the convenience, accessibility, and lower costs—when certain logistics are factored in—that so many learners seek. Online learning affords students the flexibility to manage their work schedules, travel obligations, and complex family lives all while attaining their higher education. However, online learning can increase the transactional distance experienced, with students feeling overwhelmed during the initial application and enrollment processes; disconnected from faculty, peers, and resources; and removed completely from the university culture and typical connections. Throughout their academic journey, online learners face challenges that have not been historically encountered by traditional, campus-based learners.

BestColleges.com, in their 2017 Online Education Trends Report, states that the top challenges students face when making decisions about an online university or program include “finding sufficient information about academic requirements” (#3) and “contacting a real person to ask detailed questions about specific programs” (#4). At the beginning stages of their academic journey, distance students face challenges of confirming fit with programs, and in navigating the nuances of the application and enrollment processes. Further, they are indicating that they would like a “real person” to help reduce transactional distance at this phase.

Once matriculated in their online programs, learners can feel disconnected from faculty and peers alike. Students opting to enroll into online programs trade off the benefits found in a face-to-face learning environment, most notably the immediate transactions occurring in real time and in a space where nuanced group dynamics and non-verbal communication can be easily interpreted. Moore’s development of the idea of “transactional distance” occurred when online learning was non-existent; transactional distance, therefore, can occur in all modalities, including face-to-face, and any student could feel disconnected from their classroom experience. However, transactional distance is exacerbated when students are physically removed from their learning environment, and the time and space for their learning is altered by the online modality.

Finally, online learners can often feel isolated from their university on the whole, and can be unintentionally excluded from the university culture that a typical student would experience. Traditionally, students identify with the campus brand, and they develop affinities for their universities; indeed countless research argues that students who are more engaged and connected to their institutions develop a “sense of belonging,” and that these students actually progress and succeed at higher rates. Though often overlooked by higher education leaders, online students also yearn to be part of the campus life, and to have a feeling of connectedness and to develop relationships, which is a rich part of the student experience that contributes to their overall success.

To foster important connections at all stages of the student journey, from first inquiry through graduation, higher education has an obligation to establish support mechanisms and to prepare students for their responsibilities in the higher education transactional journey. If learners’ interaction needs are not accommodated, they experience transactional distance, feelings of isolation, and disconnectedness from an unresponsive environment, possibly leading them to withdraw from an online course or program.

The Most Significant Factors Contributing to Transactional Distance

In thinking of transactional distance as an online students’ disengagement with the higher education institution, it could occur at any point in the students’ journey with the university or college. There is an exchange of influence that occurs between the student and the university, via systems or people, during the lifecycle of the student. Transactional distance could occur when there is a breach of influence in this exchange. For example:

- Lack of contact or feedback about qualifications and missing application information

- Unresponsiveness from department (or program) of study about qualifications

- Unresponsiveness from coaches or advisors

- Lack of learner readiness

- Disconnection from academic and student support services

- Detachment from campus life

- Poor course design, particularly lack of class interactions

- Unresponsive instructors

These possible breaches of influence give credence to the importance of tracking progress, and actually being proactive—rather than reactive—to students’ actions that may put them at risk of slowing progression or stopping completely. One such way to encourage progression and success is for the advising staff, coaches and faculty to develop early relationships with online students, and to then maintain those relationships throughout the students’ lifecycle. These relationships should be intentional, individually tailored, and continuous. Further, engagements with the students should be proactive and just-in-time to the students’ specific needs in terms of where they are in their journey.

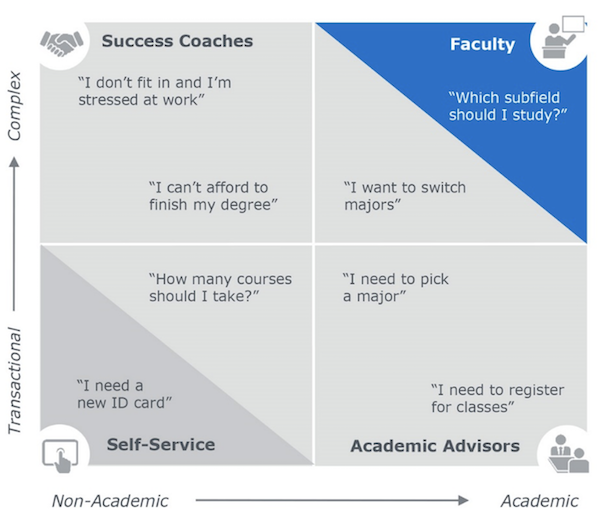

The EAB nicely illustrates those university and college representatives who can, and should, contribute to the holistic success of students: students themselves, academic advisors, success coaches, and faculty. Academic advisors typically engage in transactional relationships focused on academic matters; faculty engage with students, again, along academic lines, but in more directed ways, especially as the experts in the fields and areas of study which the students are pursuing; and success coaches often develop more complex relationships with the students related to non-academic issues. This holistic approach, especially for online students, can provide multi-layered support, making the students feel more connected and engaged throughout their academic journey. Further, this approach allows for better tracking and monitoring of the students’ progress, reducing the chance of them falling through the cracks.

Online learners have many choices for their education just a click of a mouse away, and therefore expect excellent customer service from their higher education institution. They expect to easily qualify for online programs, receive guidance for enhancing their readiness and orientation, and easily and quickly matriculate through their programs of study with compressed terms, efficient registration, and course availability for scheduling. Generally, they expect quick, relevant transactions every step of the way, from their interest in an online program to their graduation.

Online students are regularly acknowledged to be adult and/or non-traditional learners who prefer self-directed learning and experiences, and building those aspects into the system are certainly paramount. However, it must also be acknowledged that online students may need—indeed may want—guidance, support and interventions to help them advance to the next steps in the process. To reduce the transactional distance experienced by online students, support structures must be put in place to supplement the self-directed pathways, tracking their progress with trigger-alerting systems and personnel so as to intervene at the opportune moments.

The Role of Coaches in Minimizing Transactional Distance

Coaching and academic advising complement one another, and both support student success, but the approach between the two often differs in outreach and in content of support. Advisors provide the “what” for the students, in terms of what students must do in order to be successful in their programs of study and in their academic and career trajectories. Coaches provide the “how” for the students, meaning they work with students to help them build the self-advocacy and self-efficacy needed to navigate the life, social, health, commitment, time management, and other various non-academic issues that may arise on their educational journey. Perhaps the greatest benefit that coaches provided is that, early on, they develop an understanding of the students’ motivation, or the “why,” behind their educational pursuits, and they continue to encourage the students around that motivation for the duration of their relationship.

Coaches minimize transactional distance for online learners by:

- Working with prospective students through the application, admission, orientation and enrollment processes

- Cultivating a shared understanding of the “why”—the students’ motivations for pursuing an online degree

- Helping the students figure out how to be successful in their educational journey

- Providing connections to university resources, and being a liaison for the students between necessary points of contact

- Both developing routine meeting schedules as well as proactively outreaching to the students during deadlines or due dates

- Understanding what is currently happening for students at each point in their journeys

- Co-creating with the students clear success plans that account for the non-academic, life factors that may arise

- Co-creating with the students strategies to stay on track

- Motivating and advancing the students’ success plans at each meeting and interaction

- Working with the students to build their own accountability and self-efficacy

- Establishing and fostering connections with the university that are deemed critical for student success

Coaches work closely with advisors, some of whom may not have the time, training or capacity to delve deeply into the students’ particular non-academic needs. Advisors and coaches can develop a holistic case around each student, with the advisor providing the academic needs and support, and the coaches using specific techniques to work with students to prioritize and cultivate strategies to help meet established goals.

How Online Programs Can Minimize Transactional Distance

Learning House (2017) cites the 2017 National Center for Education Statistics when they discuss that the number of online degree and certificate programs has grown more than 25 percent between 2013 and 2015, with now more than 25,000 programs being offered among for-profit and nonprofit institutions. Universities wholly, and online academic programs specifically, can help to mitigate the effects of transactional distance for their online learners.

At the enterprise level, university leadership can decide to expand their online program offerings and provide more academic pathways that are fully online; foster a campus-wide culture of both academic advising and success coaching so that students are holistically supported in their educational journey; integrate their technology systems and processes so that they support a unified method of tracking and monitoring students’ progress; and invest in mobile technologies to meet students where they are, and to build connection and engagement opportunities with their online learners. An institutional culture that bolsters online learning should provide comprehensive student support services, both academic and non-academic. This would involve ensuring compliance with ADA, enforcing academic integrity, providing online students services through accessibility services, comprehensive library resources and services, counseling, tutoring, and writing supports (Online Learning Consortium, 2015). Additionally, university leadership has the responsibility to support faculty teaching online with an organizational structure and resources designated for online teaching and learning, including technology and course design supports and assurances (Mohr & Shelton, 2007).

In colleges and departments, leaders of online programs can also help to minimize transactional distance by promoting the advising and coaching models, and by developing peer-mentorship initiatives to enhance connections and engagements between students. Leaders can also encourage their faculty to engage with their online students by using available technologies to interact with students in multi-modal ways and by designing curricula that promote co-curricular and high impact opportunities to distance learners, such as experiential and service learning opportunities, thus elevating the online learning experience beyond just the online classroom.

Furthermore, leaders of online programs can incentivize faculty to teach online and encourage faculty to use their support systems, technology, instructional design, and peers. Faculty can engage in professional development about online learning, offered through collegial interactions, as well as contacting their digital learning or teaching and learning centers. This may involve participating in professional development, familiarizing themselves with best practices and trends in online learning, as well as the various student services and academic supports available to students at the university. Particularly important for quality online course design is faculty development related to quality course assurances. Academic programs and departments who encourage faculty development will make great strides in minimizing transactional distance.

Why Faculty and Instructional Designers Must Work to Minimize Transcational Distance

The majority of time spent by students at a university is in the classroom, where the academic learning occurs. The online classroom is where the partnership between online faculty and instructional designers can most directly affect the quality of students’ experience at the university. Through faculty development, instructional design guidance, as well as staff and institutional support, the faculty will have the support necessary to implement a successful online class (Mohr & Shelton, 2017). An instructional designer coordinates the support at the institution to help the faculty member structure, design and facilitate a quality online course.

To minimize transactional distance, the course design should connect students to university policies and supports as well as to course-level policies (e.g., purpose and description, communication expectations, late work, grading). Students should have no surprises about the learning expectations, which faculty can achieve by aligning course components (i.e. objectives, content, activities and assessments, feedback mechanisms) so that students focus their efforts on learning or applying what will be assessed. Some options for active learning may involve experiential or service learning, collaborative work, and formative assessment activities. Designing the course to facilitate an exchange of information among students and content, each other, community members, and faculty should keep students engaged in the course, thereby building relationships.

This transactional process of building a community of learners not only facilitates presence (Boston, Diaz, Gibson, Ice, Richardson, & Swan, 2010), but also offers a mutual pact or contract between faculty and students. In constructing this pact, faculty develop their online personas and build rapport with students throughout their programs. Faculty set and implement explicit communication and collaborative interaction expectations for everyone, including themselves, defining when and how students can expect to receive feedback on activities and assessments. Faculty execute the contract through the facilitation of the online classroom, starting prior to course start, during the course through modeling, guiding or summarizing points, and providing timely assessment of students activities/assignments. Essentially, the role of the faculty is to foster relevant, applicable learning and establish their role as the guide on the side in the online classroom (OLC New to Online Essentials workshop, 2017). Learners can respect that everyone in the class has a responsibility to interact, contributing to the overall functioning of the community.

Instructional designers guide faculty to continuously improving the course by gauging how the design and facilitation contribute to students’ learning and performance. Results from mid-course reviews, end-of-course student evaluations, student grades, student retention, students’ application of content, as well as quality course reviews could provide clues to enhance the course. Faculty participating in quality course reviews have the added benefits of learning from others’ course design and teaching practices. Translating their findings from a review of their own courses and others, with expert advisement from an instructional designer, they can put into practice design and facilitation modifications to reduce online students’ experiences of transactional distance.

– – – –

References

Best Colleges. (2017) . 2017 Online Education Trends Report. http://www.bestcolleges.com/wp-content/uploads/2017-Online-Education-Trends-Report.pdf

Boston, W., Diaz, S. R., Gibson, A. M., Ice, P., Richardson, J., & Swan, K. (2010). An exploration of the relationship between indicators of the community of inquiry framework and retention in online programs. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 14(1), 3-19. Retrieved from Eric database.

Digital Learning Compass. (2017). Distance Education Enrollment Report 2017. https://onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/digtiallearningcompassenrollment2017.pdf

EAB. (2016). Who Truly Owns Advising? https://www.eab.com/research-and-insights/academic-affairs-forum/expert-insights/2016/who-truly-owns-advising

Learning House. (2017). Online College Students: Comprehensive Data on Demands and Preferences. https://www.learninghouse.com/knowledge-center/research-reports/ocs2017/

Mohr, S., & Shelton, K. (2017). Best practices framework for online faculty professional development: A Delphi study. Online Learning, 21(4). doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.24059/olj.v21i4.1273

Moore, M.G (1993). Theory of transactional distance. Ed.: Keegan, D. Theoretical Principle of Distance Education. Routledge, 22-38.

Online Learning Consortium. (2015). K. Shelton, G. Saltsman, L. Holstrom, & K. Pedersen (Eds.), Quality scorecard handbook: Criteria of excellence in the administration of online programs. Retrieved from Online Learning Consortium website: https://onlinelearningconsortium.org/consult/olc-quality-scorecard-administration-online-programs/

Online Learning Consortium. (December, 2017). New to Online: Essentials, Part 1, Getting Started [Webcast]. Retrieved from OLC Institute website: https://institute.onlinelearningconsortium.org/mod/resource/view.php?id=80501

Author Perspective: Administrator