Published on

Assessing the State of Online Learning: Diving into the CHLOE Surveys

Introduction: Background and Scope of CHLOE

In 2016, Quality Matters, the leading quality assurance organization for online learning, agreed to join forces with Eduventures Research, a leading higher education research and advisory company. We shared the belief that online learning was becoming a fundamental component of higher education in the U.S.

Together, we formed the Changing Landscape of Online Education (CHLOE) surveys. The plan was to track forces to track online learning as it entered the mainstream, with a particular focus on growth, management, financing, pedagogy, technology, quality assurance, market differentiation and the competitive environment.

Much of the press on online learning focuses on innovative and paradigm-challenging initiatives. In contrast, CHLOE focuses on behavior in the mainstream. CHLOE uses “mainstream” to signify that online learning is no longer an ad hoc or provisional experiment at a college or university. Instead, CHLOE views online learning as a budgeted and planned activity on an ongoing basis, often specifically addressed in the institution’s mission or strategic plan. One aspect of mainstreaming is the emergence of dedicated online officers at mainstream institutions. CHLOE refers to them as Chief Online Officers (COOs), though their actual titles vary widely. The presence of a COO is both a sign of mainstreaming and an opportunity to study related trends through the perspective of the individual likely to have the best grasp of the big picture.

CHLOE data describe the responsibilities typical of the COO. More than 90% of COOs report involvement in online faculty training, instructional design, course development, quality assurance, policy setting, strategic planning and coordination among academic units. More than 75% are also involved in budgeting, LMS support, orientation of online students, managing online support services, regulatory compliance, accessibility issues, data gathering and representing the online initiative externally. Their range and depth of involvement in online learning issues make COOs the single most reliable source of information on practices at mainstream institutions.

The latest of the three CHLOE surveys gathered responses from 280 COOs spanning all sectors of higher education.[i]We hope this number will continue to grow in the fourth survey and beyond, permitting greater statistical reliability and nuanced differentiation among approaches to delivering online education. Yet much has already been established in the first three surveys.

This article will summarize key CHLOE findings on a range of issues and trends of interest to the readers of The EvoLLLution.

Online Leadership

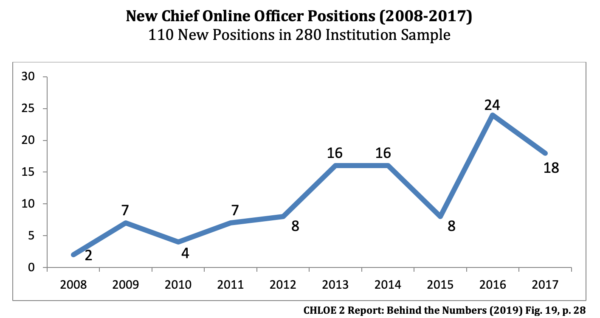

Naturally, in conducting CHLOE surveys, we have learned a great deal about COOs themselves. In addition, pioneering studies by Dr. Eric Fredericksen, who joined the CHLOE project as a contributing editor this year, trace the varied background of COOs in some detail.[ii] In what may represent a major shift, the great majority of COOs now report through academic affairs at their institutions, rather than through IT or continuing education, where many initiatives had their start. While a few institutions in our sample created such positions more than 20 years ago, more than a third of participating institutions established COOs only in the past decade. We will be interested to see whether this growth trend continues and leads to the further professionalization of this new senior management position.

CHLOE also looks closely at the online course—the basic building block of online learning—from a number of perspectives. Our data show that the fully online course predominates over the blended course across all sectors. Some institutions report a small number of face-to-face or synchronous sessions or experiences, but 84% indicate that their online courses are entirely or mainly asynchronous. It is unsurprising that the figure rises to 92% for large online enrollment programs that recruit students nationally.

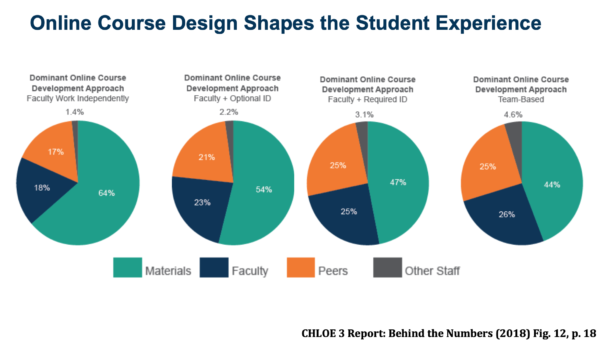

While there is considerable variation in the balance of interactive experiences provided students at the individual course level, aggregate data within and between institutions paint a strikingly consistent picture of the prevailing structure of online pedagogy. On average, slightly more than half of interaction is between students and content, the remainder is divided equally between student-to-instructor and student-to-student interaction, with just 2-3% student-to-staff. More balance among forms of student engagement seems directly related to institutional course design practices. When institutions do not provide any instructional design support for online courses, faculty report the highest proportion of student-to-content. Institutions that require instructional design input or rely on course design teams see greater student engagement with faculty and other students.

Do Instructional Designers Make a Difference?

CHLOE findings show that instructional designers make a significant difference in the effectiveness of online learning. COOs from institutions that require instructional design input to course design also report better online student performance compared to on-ground students, and more consistent use of the LMS and online tools across the online curriculum.

With mounting evidence that instructional designers improve the effectiveness, quality, and consistency of online courses, CHLOE has tried to understand why fewer than half the institutions in our survey require its use. For many, including a high proportion of community colleges, it is clearly a matter of perceived unaffordability. But CHLOE has found faculty are resistant to any requirement that limits their independence and academic freedom to shape their online courses as they choose, regardless of resource limitation.

Innovation vs. Stabilization

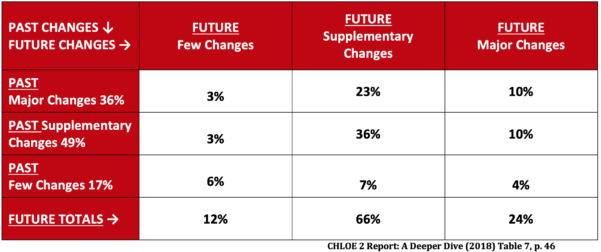

By its very nature, online learning lends itself to innovation, as tools and techniques are introduced to enhance its effectiveness and efficiency. In Fredericksen’s studies of four-year and community college online leaders, more than three out of four indicated that they are seen as change agents in their institutions. However, when CHLOE asks COOs to estimate the amount of change over the past three years and predict the extent of change in delivery of online learning at their institution in the next three years, only 36% reported major changes in the recent past and even fewer (24%) report plans for major change in the near future. The great majority report only supplementary changes in both timeframes. While this level of innovation seems sufficient to keep online learning moving forward, these responses also indicate a tension between innovation, with its risks and rewards, and the pressure to maintain a stable environment in service to ongoing programs.

Is Online Learning a Net Cost or a Profit Center?

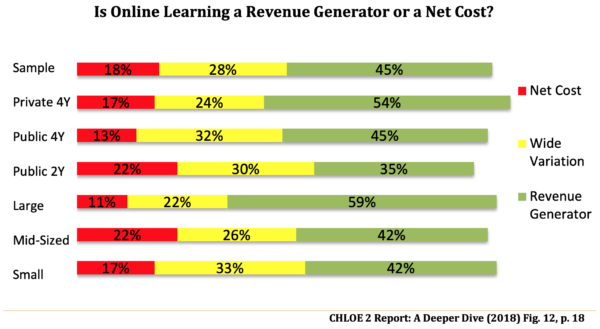

Much has been written about the true costs of mounting and maintaining online programs. Results can vary substantially, based on very different online development models and the biases of the investigator. There is also lack of agreement on the costs that should be counted against online programs and those from which they should be exempt. CHLOE has chosen to simply ask COOs for their bottom line: Is online learning a net cost or revenue generator at their institutions? In the sample as a whole, 45% judged online learning to be a net revenue generator and only 18% thought it was a net cost, while 28% thought it varied. Still others offered more nuanced judgments. Among the largest online enrollment institutions, 59% consider online a revenue generator, and community colleges are least likely (35%) to view it in that light.

Thus, CHLOE results reflect continuing difference of opinion. In the survey, more positive views of online learning’s revenue potential correlate with larger enrollments and more ambitious plans to expand and to implement technical and pedagogical changes.

Online Learning Models

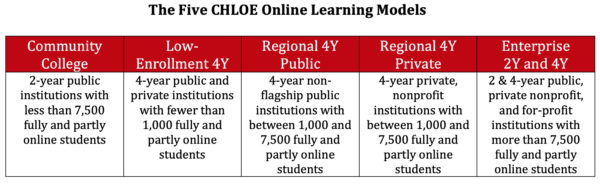

One goal of the CHLOE project has been to identify different approaches to online learning that cluster institutions with common characteristics, practices and plans. We began with simply grouping institutions by control (public, private, for-profit), scope of program (2-year and 4-year), and online enrollment (under 1,000 online students, 1,000-7,500 and above 7,500).

With three years of data, we have begun to combine control and size to see if other characteristics line up consistently in these groupings. The early results are encouraging, but further subdivision of the resulting models will require further study. Ultimately, we hope that institutions will be able to find in CHLOE a peer group with which to compare their practices, plans, policies and performance. Such comparisons might stimulate debate within institutions to evaluate their approach to online learning issues and consider alternatives. The five CHLOE online learning models at this stage of our work are as follows:

Below are a few examples of how our preliminary models compare with one another. In these examples we can see striking contrasts, the need to further refine the models, and questions that demand follow-up.

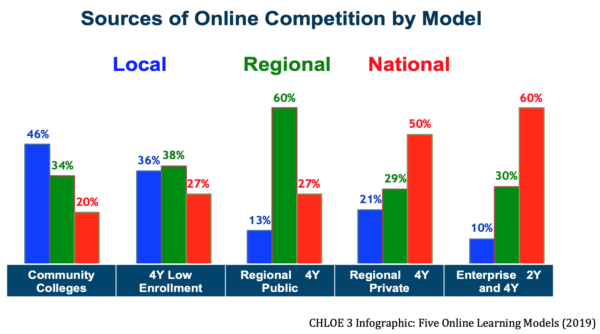

Competition

The following graphic illustrates that the majority of Enterprise schools focus on national competition, the majority of Regional Publics focus on regional competitors, and most Community Colleges are concerned about local and regional competitors. A majority of Regional Privates, however, identify national competition, perhaps reflecting their ambition to recruit and compete nationally. The relative balance between local, regional and national competition identified by the Low Enrollment group may indicate a need to subdivide this model into institutions that have very distinct views of their role in online learning and the threats they face.

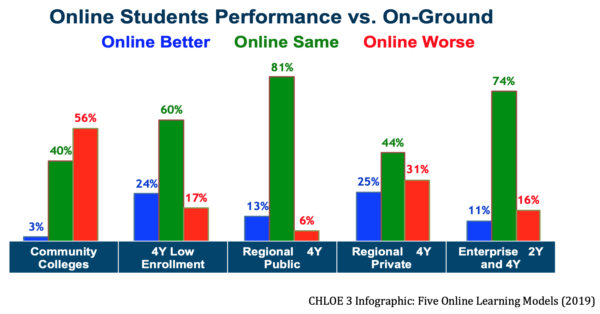

In the following graphic, CHLOE asks COOs to compare the performance of online students to on-ground students, based on their most-used performance benchmark.

The benchmark chosen was typically course grades, term-to-term retention or graduation rates. Ninety-four percent of Regional Publics judged their online students to be performing as well or better than on-ground students, followed by 85% at Enterprise schools and 84% at Low Enrollment institutions. These are impressively large majorities, indicating that schools in these models have largely overcome any gap in performance between their online and on-ground programs.

The corresponding figure for Community Colleges is only 43%, indicating that online students in a majority of institutions in this model are not performing well. Regional Privates show more mixed results among institutions, with two-thirds reporting comparable or better results for online students and nearly a third reporting worse results. These are concerning results for the model that has the highest proportion of fully online students and online graduate students. Both of these models raise questions on which future CHLOE surveys will attempt to shed light.

More comparisons among the five models can be found in the CHLOE 3 Report,Behind the Numbers (2019). Other topics included in this article are developed at greater length in the CHLOE Reports.

References

[i]Garrett, R., & Legon, R. (2019). CHLOE 3 Behind the Numbers: The Changing Landscape of Online Education 2019. Retrieved from Quality Matters website: qualitymatters.org/qa-resources/resource-center/articles-resources/CHLOE-3-report-2019;Garrett, R., & Legon, R. (2018). The Changing Landscape of Online Education (CHLOE): A Deeper Dive. Retrieved from Quality Matters website: qualitymatters.org/qa-resources/resource-center/articles-resources/CHLOE-2-report-2018; Garrett, R., & Legon, R., (2017). The Changing Landscape of Online Education (CHLOE). Retrieved from Quality Matters website: qualitymatters.org/qa-resources/resource-center/articles-resources/CHLOE-report-2017.

[ii]“A National Study of Online Learning Leaders in U.S. Higher Education” (Fredericksen, 2017) and “A National Study of Online Learning Leaders in U.S. Community Colleges” (Fredericksen, 2018)

Author Perspective: Analyst