Published on

Return to Ritual & Return on Risk: Ritualized Learning for a COVID World

In 1985, Bennis and Nanus first introduced entrepreneurs, innovators and leaders to the volatile, uncertain, complex, ambiguous (VUCA) environment. For decades the term VUCA was sprinkled in keynotes, TED Talks, articles, and books. In 2020, a pandemic-infused VUCA context washed over communities, countries and continents indiscriminately. In 2021, Ted Chaiban, Regional Director of UNICEF Middle East and North Africa, highlighted the impact as “humanity faced an unprecedented disruption in education.”

This disruption heightened educational blind spots, gaps and inequities and amplified problems in learner engagement, motivation and self-efficacy. Moving classes online threw educators and learners alike into a whirlpool of various risks including, but not limited to, digital literacy and technological competencies; economic gaps, geographical restrictions, physical, personal and social diversities and inequities; spatial, emotional and cognitive blurring of social boundaries; and individualized responses to change, the unfamiliar, social uncertainty and chaos. As a consequence, we have all become intentional learners navigating the unchartered emotional, psychological, physical and social waters of COVID learning, working and living.

Despite the chaos, the situation has also increased pedagogical risk and reward, accelerated innovation in education and created unimagined learning opportunities, as almost everyone experienced intentional unlearning, relearning and new learning. During times like these, individuals crave autonomy, mastery and agency; ritual, risk and play provides such a framework. This paper aims to do its part in empowering learners by synthesizing a reflective framework with a process as ancient as civilization: the ritual. To this end, the crucible we are going through just might revolutionize education’s outdated conventions, as ritualized learning transforms risk to reward, play to potential and differentiated reflection into a model for our times and beyond.

Education As a Ritualized Space

Education is a ritualized experience comprised of mini-rituals where participants focus, act and reflect on, in and through what-if and as-if scenarios. Involvement in play-filled risk and risk-filled play builds a healthy sense of belonging, self-confidence and resiliency (Brown, 2010) among learners as they rehearse roles, identities, skills and purpose within the safe confines of the ritualized space.

All too often, however, classroom spaces become fossilized into stagnant routines, meaningless habits and irrelevant procedures: agendas, roll calls, redundant announcements, passive lectures, regurgitated textbooks, etc. Not only are these calcified practices unresponsive to participants’ needs, their repetition zaps energy, creativity and engagement, but they also instigate unwanted habits in learners, such as coming late to class and leaving early, not being prepared, not listening, not discussing, not caring. The same is true of meetings. Fossilized rituals are purposeless routines and the antithesis of what we need, especially now in our heightened VUCA environment.

The new reality of masked, hybrid and online learning and meetings involves various degrees of anxiety-inducing risk and playful potentiality, and the degree of each depends on the individual’s predilections to change and willingness to engage in the seriousness of play. Thus, online learning alters the conventional face-to-face learning ritual by changing the place, time, attitude and roles we are accustomed to in conventional learning. We have entered a universe where status is overturned, private spaces are public places, students are technological specialists, veterans are amateurs and everyone is a learner. We have entered the liminal universe of ritualized learning, and this may be the only thing that protects us from drowning in the hostile waters of a VUCA reality.

But before presenting how ritualized learning can mitigate the negative impact of our current situation, ritual needs clarification, since it also has been calcified by overuse, misuse, and abuse.

Turning Ritual into Ritualized Learning

Rituals, unlike routines, are the regular and consistent practices of meaningful actions that demand of their participants focus, action and reflection (FAR). According to prominent cultural anthropologist Victor Turner (1969), rituals are special spaces and times “open to play of thought, feeling and will; in them are generated new models” (vii) for the individual and society. These models are created and playfully explored through “unprecedented performances” (1982, p57) with the potential of “re-structuring. . . reality” (1986, p168).

Furthermore, ritualized experiences occur within a predictable, well-defined framework.

The distinct beginning, middle and end structure holds the unpredictable, risk-filled play and play-filled risk that has the promise of “painting another picture, that of cultural ‘agent’, energetic, subversive, creative, socially critical” (Grimes, p144).

Seriously playing in what-if scenarios increases the risk/reward/failure quotient, but the ritual structure makes the impact of possible failure less severe and daunting. The ritual’s “temporariness” builds secure, safety and reassurance within the participant because play is its own world (Fink, 1968, p21). Furthermore, ritual’s democratic or equalizing nature safely invites new narratives that challenge, ignore and subvert status, position, authority in order to play with new possibilities. Like theater’s rehearsal space, ritual encourages the testing of roles, actions and ideas before participants apply them real world.

This description of ritual can be applied to education as a macrocosmic ritual comprised of micro-rituals. The child leaves their home environment for the liminal experience of the classroom’s serious play only to re-enter society years later with new skills, ideas and perspectives. The metaphors surrounding education reflect the rite-of-passage ritual (Van Gennep, 1960): Participants pass from grade to grade based on progress reports. Promotion, probation, suspension, expulsion, acceleration can occur before the participant ceremoniously walks across a physical stage marking their (re)entry into the real world.

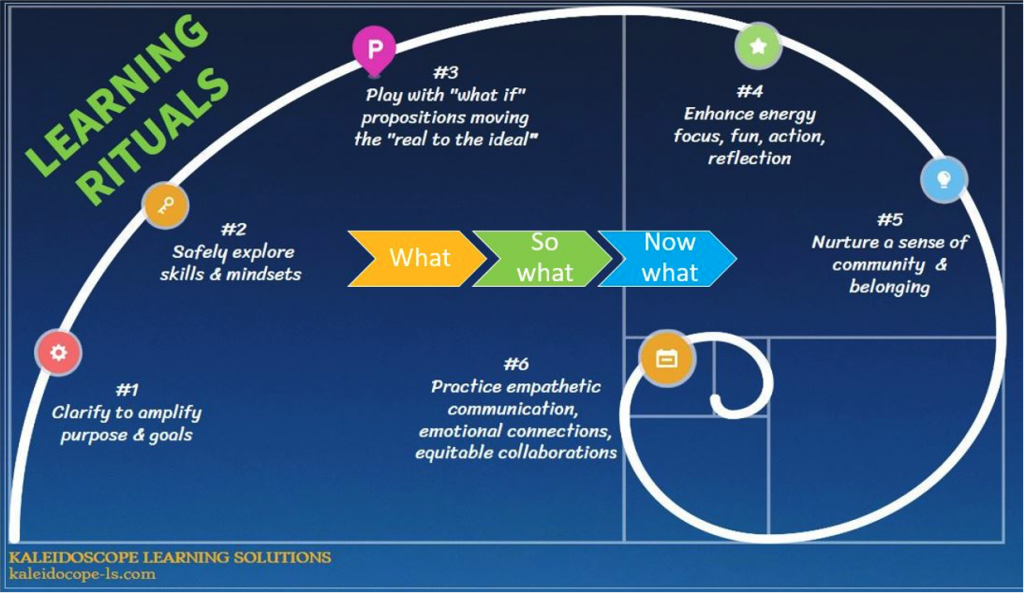

Likewise, education’s play space is marked with practice questions, role-playing, simulations and experiments before the final exam. Here, learners practice different roles, positions and perspectives while building empathetic communication and equitable collaborative practices. Overall, the elements inherit to ritual as defined by Turner and Van Genep create the conditions that will make learning a valuable, relevant and transformative experience. (Image 1) Thus, while the ritual situation of a unique time and space impact the risk/reward/failure quotient, one essential ingredient acts as a “ritualizing” catalyst. 3D-Briefing is an essential agent in the transformation toward ritualized learning.

3D-Briefing for Ritualized Learning

As already stated, many of our actions are rituals that have fossilized into static routines, bad habits, unresponsive procedures divorced from purpose and relevance. One simple yet effective way to de-calcify meetings and classrooms is to frame every activity within the 3D-Briefing model. Originating from paramedic training (Rolf et al) and adopted as a corporate feedback tool, many are familiar with the three simple questions: what, so what, now what? But, 3D-Briefing applies this model FAR (Focus, Action, Reflection) beyond the original intent. If we agree the ideal goal of learners is to seek “a transformative experience that goes to the root of each person’s being and finds in that root something profoundly communal and shared” (Turner, 1969, p138), 3D-Briefing accomplishes this FAR ideal in a manner accessible to any learner, in any discipline, of any age and ability (Boyko-Head 2020). And it is this deep exploration of purpose that transforms any activity into a ritualized learning experience.

First, these three questions, like ritual, are accessible to any willing participant. Second, they encouragea play-filled energy that is safe, secure and fun while rehearsing empathetic communication, emotional connectedness and equitable collaboration. Personalized responses mean prior knowledge, experience and perspectives are valued. This builds a sense of belonging or ritual togetherness where each person is separate yet connected in their process of “becoming“ through respectful dialogue and sharing. Finally, 3D-Briefings’ familiar, repetitive questions and individualized, differentiated responses work toward transforming the space into a micro-ritual that lowers the risk/failure equation by increasing the reward potential.

While I cannot over-estimate the flexibility, value and ritualized significance of 3D-Briefing to all learning levels and disciplines, the significance for minimizing risk and maximizing reward is my current focus. That role is fulfilled in 3D-Briefing’s final question–now what?–and its ability to transform any mistake, blunder or failure into a rich learning experience.

Turning Risk into Continuous Reward

Typically, risk is viewed as something dreadful and threatening. It is a deviation, an abnormality, unwanted interruption or intrusion. Everyone stands at different levels when it comes to risk: Some embrace risk and dive in wholeheartedly, while others dip a tentative toe in the pool and cautiously wade in the shallows, others avoid the water at all costs, content to stay on familiar ground. The same diverse relationship can be said of learning. Fear of failure is a real risk in education that impacts learners and instructors alike. Over-assessment, teaching to the test and test anxiety are some indicators of our obsession with perfection.

Teacher image is also risked at every turn with learners, colleagues and administrators. Expectations of what good teaching should look, sound and feel like challenges relationships with colleagues and learners. Getting to know learners as people, not just students, can also challenge expectations and assumptions regarding quality education, student-instructor boundaries, definitions of authority, etc. Yet when we hesitate to build ritualized time in our classrooms, especially our online classrooms, what we are risking may be more significant than reputation, expectations and out-dated assumptions (Boyko-Head & Chisu, 2021).

When risk is positioned within the secure confines of ritualized learning, it can take on a different form: an affordable loss, unanticipated gain, unexpected opportunity and expansion of experience. Financially, the risk-reward concept states that risk is measured against its potential gain—the higher the risk, the higher the potential gain (Investopedia, 2021). While this may be true in terms of economics, education requires a less random method to assess risk because futures hang in the balance.

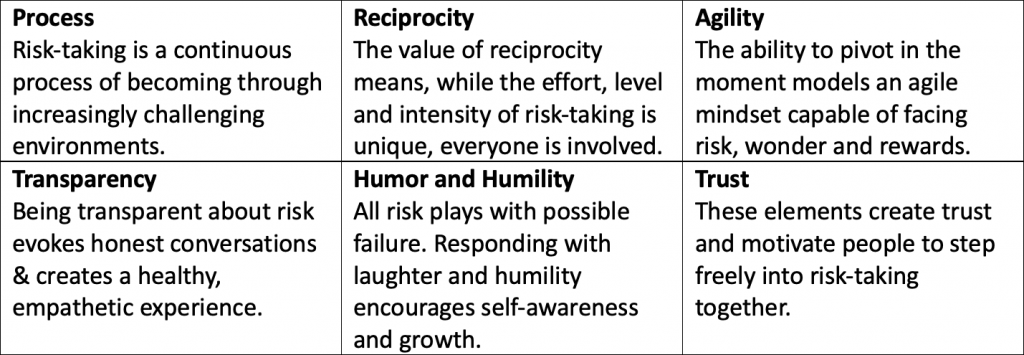

There are six key elements for transforming risk into reward (Table 1). First, risk-taking is a dynamic process involving varying degrees, frequency and impact determined by desired and anticipated outcomes as well as the socio-emotional context. This awareness of context emphasizes the reciprocal nature of risk’s shared, transformative process. Everyone— educator and learner–is taking a risk of sorts with the level, intensity and outcome differentiated for each person. Third, risk requires a willingness to play with the stakes and demonstrate an agile mindset capable of pivoting from disruption to reward. In fact, play might be the risky element for some. For others, agility may be the risk, due to a fear of failure. However, honesty and transparency in communicating what is at risk and why lowers the danger and increases new awareness, learning and possibilities. Thus, the concept of mistakes and failures within the ritualized space makes humor and humility easily accessible. Laughing at our errors intensifies play quality, enhances transparency and honesty and reinforces the reciprocal nature of the transformative process. Within the ritualized learning space, risk is something to gamble with, and this collective gambling builds trust and moves the group toward authentic community, equity, autonomy, engagement, agency and so much more. Thus, these six elements generate an interconnected system of ritual belonging, playfulness and growth.

When this system is working, the evidence is identifiable. It is revealed in high attendance, more accountability and preparedness for class, involvement in small or large group discussions and increased openness toward our lives as humans, not just learners. This last point builds the transparency, humor and trust that reinforces the ritual experience. Evidence of this is the continual presence of a pet on a learner’s shoulder and missing it when it isn’t there; having a brief conversation with a parent or roommate that waves to the class; welcoming a child on their parent’s knee as they present their power point; a class carrying on as the instructor struggles to return on line after a power bump; learners entertaining the class with their musical talents or giving a virtual tour of their home-based classroom, sharing significant objects, performing mindfulness exercises together and even sharing a new game, joke or story.

Conclusion

The COVID landscape has challenged the individual’s relationship to risk and learning by catapulting everyone into risk-filled situations requiring intentional unlearning, relearning and new learning. Unlike previous disruptions, the pandemic threatens every aspect of our lives, from health and emotional well-being to personal and professional identities. This unpredictable time forces people to forfeit the familiar and jump into unfamiliar personal and professional relationships, patterns and behaviors.

Our educational institutions have finally leapt into the future, as ritualized learning enables us to gain an understanding of, a reflection on, and a transitioning toward new states of thinking, being and acting. In this journey toward learning empowerment, any activity can be ritualized when learners take the time to 3D-Brief the experience, collectively or independently, publicly or privately. The simple yet mighty questions establish the ritual structure of beginning, middle and end and maximize the return on risk by minimizing negative impact.

In these times of disruption, risk-filled play in rituals is needed more than ever. Rethinking and redesigning the learning space as a ritualized experience can provide educators and learners with the lifelines they need to each other, to their own autonomy and agency and to the agile thinking that will help them navigate the diverse situations and unfamiliar waters of today and tomorrow.

Author Perspective: Educator