Published on

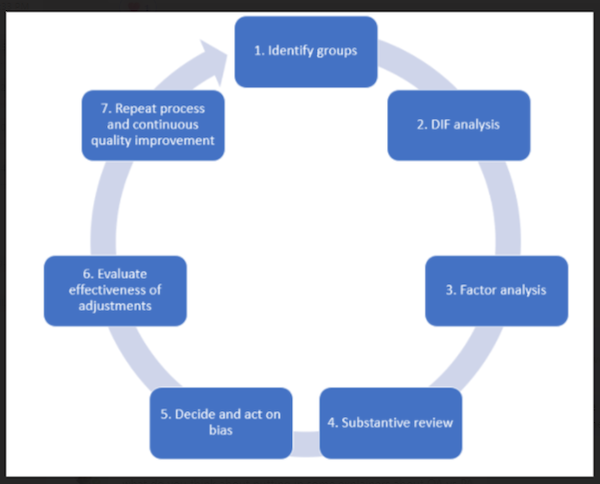

7 Steps to Identify and Address Bias in Educational Assessments

Heather Hayes | Senior Lead Psychometrician, Western Governors University

Goran Trajkovski | Program Manager, Western Governors University

Marylee Demeter | Senior Assessment Developer, Western Governors University

Concern over fairness in assessment outcomes has taken center stage in the educational assessment industry in recent years. When an assessment is fair or free of bias, students have equal opportunity to demonstrate knowledge, skills and abilities regardless of identity and personal characteristics. Bias in assessments threatens the reliability and validity of assessment scores and outcomes, limiting their usefulness and instilling a lack of trust and confidence among students, hiring institutions and the educational community in the credibility of standardized educational assessments. In higher education, assessments with bias can interfere with student learning and progress toward educational objectives.

In competency-based higher education, biased assessments may erroneously classify not yet competent students as competent (and vice versa), resulting in lack of preparation for a job or career and a failure to recognize students who are prepared. Although preventative steps should be taken during initial item development, including bias and sensitivity reviews, it is still possible for items to function differently than expected. Therefore, a system should be in place at educational and testing organizations to statistically examine all assessments for potential bias once they become operational. In this article, we provide a step-by-step guide on how to identify and address bias in educational assessments. By following these steps, you can ensure that assessments produce fair and valid outcomes and interpretations.

Step 1: Identify the Groups of Students Who May Be Vulnerable to Bias

In Step 1, groups of potentially vulnerable students are identified. This could include groups based on language, culture, gender, race, income or any demographic variable of concern. For example, students for whom English is a second language may have more difficulty with assessments that require reading, writing or verbal (oral) components compared to primarily English-speaking students. Similarly, students with different cultural backgrounds may struggle more on assessments related to history, humanities and communications. Faculty or instructors may notice that certain groups struggle in class, on homework or with the assessment itself. Students themselves may lodge complaints over the perceived fairness of an assessment or even a particular item within the assessment.

Once vulnerable populations are identified, then a psychometrician or assessment specialist should proceed with gathering assessment and item response data to begin the investigation. The group identities should be clear in the data. For example, if gender is of concern, then students should be sorted into categories based on how the student identifies him, her or themselves. Perhaps even an intersection of identities is of concern such as female minorities versus white males (if there is a sufficient sample size for each category).

Step 2: Conduct a Differential Item Functioning (DIF) Statistical Analysis

Step 2 involves using statistical methods such as DIF analysis to identify items on the assessment that function differently between groups when controlling for overall ability (i.e., total score). There is always a focal group (i.e., the protected or vulnerable group such as minorities, females) and a reference group (i.e., white, males). The most common example of differential item functioning is when an item is more difficult for members of one group than members of the other group despite being matched on ability or overall score (uniform DIF). A second example is when an item discriminates more among members of one group than another despite being matched on ability, i.e., one group is measured with better precision than the other (non-uniform DIF).

The challenge of this step is that there are many available methods for testing statistical DIF—observed score methods that are parametric or nonparametric and those based on Item Response Theory (IRT). Each has strengths and weaknesses and is more appropriate for certain scenarios and certain item types (e.g., dichotomous versus polytomous) and test modalities (e.g., multiple choice versus performance assessments). Though it is common to use multiple methods and select an item as potentially biased if a) the item is flagged by any method or b) the item is flagged by all methods. However, nearly all methods require a sample size of at least 200 per group to provide stable and reliable estimates. Therefore, DIF analysis should not be conducted until the sample size reaches this point. It is crucial to note that DIF does not automatically equate to bias. Rather, it is a red flag or sign of potential bias that requires further investigation.

Step 3: Conduct a Factor Analysis and Estimate Reliability

If you have not recently performed a factor analysis on the assessment, now is a good time. Factor analysis is crucial for testing construct validity, addressing the question, Are we measuring what we think we’re measuring? For example, if you think your arithmetic assessment items fall into four categories (addition, subtraction, multiplication, division) because each item requires one of these four types of operations, then when you conduct a factor analysis on these assessment scores, the result should be a four-factor solution in which each item more strongly loads onto (i.e., correlates with) its theorized factor (e.g., operation) than other factors. Since factor analysis is so strongly tied to validity, it is no surprise that it is also relevant to item bias.

Namely, if an item is multidimensional and one of these dimensions is construct-irrelevant, it is biased if groups differ on the construct-irrelevant dimension. However, if groups differ on a dimension that is relevant to the construct, then the DIF is benign in nature and there is no bias. Thus, conducting a factor analysis can help determine if an item is biased as well as explain why it is biased without further substantive review. A factor analysis is also crucial for testing an important assumption in Item Response Theory (IRT)—unidimensionality—if one plans to use a unidimensional IRT approach to testing for potential item bias. For performance assessments that are graded by humans, it is also recommended that scores be evaluated for interpreter reliability or evaluator bias (e.g., strict versus lenient). This step is crucial, not only for the purpose of establishing validity but for ruling out any impact of inconsistencies or errors in scoring that could also contribute to DIF or bias in performance-based assessments.

Step 4: Conduct Substantive Review of DIF Items

Once items have been flagged for DIF and potential bias, they are submitted for further scrutiny from subject matter experts (SMEs) in the course material. To avoid confirmation bias, all items must be reviewed, and the reviewers must not be aware of the DIF results. The review can be conducted in a structured meeting among multiple SMEs such as assessment developers, course instructors and evaluators in the case of manually graded performance assessments. However, in a large-scale testing or educational organization where hundreds of assessments are developed and maintained, it may be more feasible to provide SMEs with a rubric for conducting the review asynchronously. Items should be reviewed for any bias toward members of the groups identified in Step 1. Examples of construct-irrelevant item features include slang, pop culture references, awkward wording, poor grammar, run-on sentences and confusing text or objects. Moreover, items should be reviewed for stereotypes, diversity and inclusion. For example, a scenario-based item stem that describes a work team, both males and females and multiple ethnic groups should be represented—and not in stereotyped roles such as white males being the manager, doctor or senior member of the group. It is also useful to consider a cognitive think-aloud procedure in which SMEs who represent different groups go through the process of responding to items to pinpoint any difficulties or confusion in the response process that uniquely affect members of a particular group. For each item, the reviewer states whether the item is biased and, if so, toward whom and why.

Step 5: Decide and Act on Bias

Once statistical DIF, factor analysis and substantive DIF reviews have concluded, results can be collated, and a determination of bias can be made. Namely, an item is determined to be biased if it meets the following criteria: 1) flagged as having C-level DIF (DIF with a large effect size), 2) the item has a construct-irrelevant factor or is identified as being biased by a reviewer. If it only meets #1 but not #2, then the item cannot be confirmed as biased. If an item is confirmed as being biased, then the item should be discarded and replaced with a healthy, banked item. If item banks are low, then the item can be modified and field-tested prior to be using used on a live assessment form. If the item is not confirmed to be biased, then the item can be retained and monitored more closely over time in case it becomes problematic and requires further review.

By using this decision criteria, one can avoid unnecessarily discarding useful and well-constructed items while focusing attention on identifying and removing items that are truly biased and may impact the overall score or pass rate.

Step 6: Evaluate the Effectiveness of the Adjustments Made and Address True Group Differences

There are several ways to measure the effectiveness of removing biased items from an assessment. If there is a large amount of DIF in an assessment, then there will likely be group differences in mean assessment scores or pass rates. A psychometrician should conduct a statistical test to determine if these differences are statistically significant (i.e., not due to chance or sampling error). If group differences are statistically significant, then impact is confirmed. If there was impact prior to making changes to the assessment that disappears after making these changes, then there is evidence of improvement. Also, instructor and student feedback should improve.

However, if impact and complaints occur despite a lack of biased items on the assessment and construct validity has been confirmed, then it is possible that this impact reflects true group differences. For example, members of one group may have studied the course material more, have a better grasp of the course material that they have studied or not have as much educational experience with or prior knowledge of the content covered in the course. At this point, there should be an investigation of the source of impact such as differences in study behavior, course activity, access to learning resources, instructor guidance and so forth. It is also possible that learning resources provided in the course contain bias that carries over to assessment performance. Thus, a review of learning resources for bias and sensitivity is also recommended. Once gaps on the curriculum side of education are identified, they should be closed and the focus should be on minimizing differences in learning and assessment performance through more formative practice, instructor guidance and feedback and various forms of aid.

Step 7: Repeat Process and Continuous Quality Improvement

Once the previous steps are completed, bias has been identified and eradicated and true group differences have been investigated and addressed. The assessment should undergo this process again if and only if changes are made to the assessment. For example, item content may become obsolete or irrelevant as a result of changes to the curriculum or shifts in learning theory or industry relevance (e.g., changes in technology, medicine, business, tax law). Educational and testing organizations should also continuously monitor the reliability and validity of assessments in general to maintain assessment quality and prevent item bias.

By engaging in continuous quality improvement, educational stakeholders can be confident that their educational assessments are undergoing the necessary scrutiny to avoid and minimize bias toward protected and underserved groups.

Author Perspective: Administrator