Published on

The Benefits of Financial Modeling for Online Education

Why financial modeling is important

The COVID-19 crisis has forced higher education institutions across the country to deliver remote, distance education. After the crisis, many institutions will want to move beyond remote education, which was rapidly put in place this academic year and into the development of well-designed online learning opportunities. In fact, many institutions were already on this path before the crisis struck, and they have a competitive advantage now.

The success of a long-term online initiative will depend on more than course content and the instructional quality of online offerings. It also will depend on the development of financial models for online initiatives and the integration of these models into the institution’s overall budget and multi-year strategic plan.

Financial models sound complicated–and they are–but when done well, they provide an accurate reflection of an online initiative’s many pieces–both in and outside the institution–that must work together like cogs in a machine to ensure the initiative’s success. While not all aspects of an online program can be quantified (e.g., the years of research that inform a course’s content), financial models document and quantify the many aspects of integrated work needed to implement an online initiative. These go beyond dollar figures for salaries or contracts to include areas such as student support, digital marketing, coaching and recruiting, professional development, video, instructional design, and a multitude of others.

Parts of a financial model

The basic parts of the financial model are inputs customized to each institution and program, including the program’s lifespan, number of students expected each year, tuition charged, number of courses offered, number of faculty required to produce and teach the courses, faculty salaries, and marketing, licensing, or online project management (OPM) vendor fees. While some of these inputs will be estimates, they must be informed, adjustable estimates that will give leadership a realistic vision of what will be required to make the program sustainable over time.

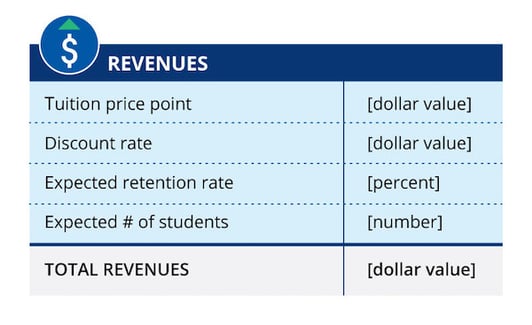

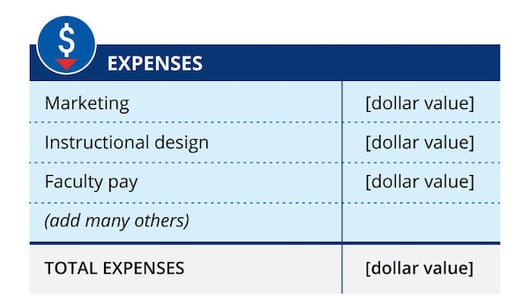

The following provides a simplified overview of revenue and expense inputs for an online education program, followed by examples of related questions that must be answered to determine the inputs.

Sample Inputs for an Online Education Program

Related questions to answer:

- What is the expected number of students? Over what time period? Will the program last indefinitely?

- How much financial aid on average is expected per student? Yearly or by term? How will financial aid affect tuition revenues?

- What student retention rate should be assumed? Will this amount be consistent across programs?

Related questions to answer:

- How many FTEs are needed for marketing? Expected outsourcing costs? How about digital marketing? Efficiencies of scale? When will efficiencies kick in?

- How much time can one instructional designer contribute to one course? At what rate? How many courses can that person complete in a given time frame?

- How much will faculty be paid to produce an online course? Or will they be given course off-load instead? Who makes that decision?

Why model creation is hard: it’s not the math

Although these models are neither quick nor easy to build, input assembly serves as the best tool to illuminate what is important to both the initiative and the institution. The process demonstrates what pieces are required, how they must work together, where there may be gaps in institutional plans or resources, and the significant additional work required to make the initiative a success.

Consider the following examples:

Example one

A project management team focuses on integrating internal online initiatives into the whole campus infrastructure. During preparatory meetings and workflow mapping, the team discovers that the financial aid office will almost certainly be inundated by processing requirements for online students at certain times of year, above and beyond their typical work.

Questions to answer: Should the online initiative pay for extra FTEs for financial aid? If so, when?

Example two

The project management team discovers that because of federal regulations, availability of financial aid may partially determine online program start dates.

Questions to answer: Should financial aid regulations focused on traditional, in-person term lengths determine start dates and term lengths for online learning when, for example, it is known that potential online students prefer shorter terms? Does term length or financial aid affect recruiting more? How can both be addressed?

Example three

The online education program will need professors from different schools to teach courses. Each school has its own budget, salary structure and faculty teaching requirements.

Questions to answer: Whose budget will pay for online teaching salaries? What effect does online teaching have on in-person faculty course loads? What is the revenue split? Who makes these decisions?

Answering these questions and hundreds more is essential to developing a comprehensive, effective model, which in turn is essential to successful online integration in an institution.

Point of failure

Inputs to the financial modes must be thought through carefully. This effort requires time, an in-depth knowledge of unit requirements across the institution and a good deal of financial knowledge. It is rare to find all these capabilities in any one unit. For example, an institution’s online education leaders are likely experts at instructional design but may not be as financially inclined. In this case, they may have to rely on the financial office to build models for them. But the financial office may not understand the complex assumptions the online unit makes, which are foundational to the successful modeling of the whole initiative. Without a common working vocabulary that the different groups can share, the model may be significantly flawed and the cogs stuck. A lack of understanding across the institution can be the point of failure.

Benefits of financial modeling

Despite the challenges of financial modeling, once they are in place institutions can use their models to forecast for years, upgrading and adjusting them as needed. Among the benefits are:

- A significant increase in transparency among stakeholders. Siloes are a given at most institutions. Openly sharing financials among schools and colleges can create a clear point of trust and communication. Inclusion of deans or other academic leaders throughout the financial modeling process, from deciding on assumptions to determining revenue distribution, can go a long way to foster collaboration and trust.

- A clear basis for decision making. Financial models provide a foundation of knowledge to inform decisions with solid data. Consider, for example, the staff hours required to implement a new program. With a firm understanding of the hours required, institutions may be able to draw upon existing FTEs, or if additional time is required, determine if an internal hire is needed or if the work can be outsourced. Once inputs are correctly integrated into the model, institutions can test various scenarios, providing multiple options for decision makers to consider.

- Flexibility for continuing education. Similar financial modeling can be contextualized for continuing education initiatives.

Conclusion

While the scope of financial modeling for online initiatives is significant, investments in these models will reap significant rewards. The process will mirror the actual integration, forge clearer lines of communication and collaboration among units, provide a solid foundation for financial planning and institutional growth, and build capabilities in data and analytics that inform strategy and decision making. With the support of trusted advisors who can bring industry expertise to bear on specific institutional resources and needs, institutions can build financial models that will, with continual agility, serve them well for years to come.

Editor’s note: This article was submitted on April 15, 2020.

Author Perspective: Administrator