Published on

The New Dimensions of Scholarship: Shifting Faculty Development from Morbidity Models to Student Success Predictive Analytics

Professor Perez looked left from her third computer monitor as an alert flashed in her notifications bar. A small yellow flag appeared, softly blinking. She paused her reading of a student submission analytics report on her center monitor to click the flag. A smaller pop-up box appeared, indicating that a student in one of her cohorts had not achieved several sequenced competencies. The summary screen displayed the history of artificial intelligence (AI) prompts sent to her student, Jayden. Despite the system’s best efforts, Jayden was still falling behind her peers. The system had proposed a one-on-one meeting with Professor Perez and Jayden that fit both of their calendars. She accepted the appointment and switched back to the analytics report she was reviewing.

Later that afternoon after her last class, Professor Perez sat back at her seat in the office and clicked the link to her meeting with Jayden. “Hello Jayden,” said Professor Perez, “It seems that you have been experiencing some challenges with a few of your assignments.” Jayden appeared quite tired as she responded, “Yes…It’s been tough lately and I can’t seem to find the time to catch up.” “You were doing fine for the first few weeks,” commented the professor. “What’s changed?” Jayden then described a series of personal challenges, chief of which was family disruption due to the pandemic. Her mother had lost her job forcing her family to relocate and call on her to care for her younger siblings during the displacement. “I can see from your academic record that you have been a student in good standing, Jayden,” offered the Professor. Noting that the AI had not flagged any academic progress delays due to cognitive deficits, she asked, “Would you like me to shift you to another one of my cohorts moving at a pace that better fits your circumstances?” “You mean I can make up the work I missed?” asked Jayden. “Given the merit of your efforts to date, I think you have earned it, Jayden. You are two weeks behind and we can shift you into the Fusion Cohort for this group of competencies, and your work on your portfolio can continue,” offered Professor Perez. “My mom is settled now, and I’d love the opportunity to get back on track. Thank you, professor. Thank you so very much,” replied Jayden. “Life always gets in the way Jayden,” offered Professor Perez. “While we cannot and should not compromise our teaching and learning standards, we have built these opportunities into our systems and practices for students like you to better succeed. I’ll see you in next week’s seminar.”

Faculty and the “wicked problem” of student success

Clearly, there are countless variables in the above scenario, and most of us have likely heard similar (and quite different) genuine reasons and unacceptable excuses for students failing to reach academic requirements within courses. The research on student success is vast. It addresses aspects of the learners, faculty, and the broad range of services and support that we offer across higher education. And that’s just for starters. Postsecondary indicators of success include preconditions extending back to preschool (or prenatal for that matter). On the quantitative side a long list of indicators led largely by high school GPAs appear to work in tandem with an equally robust list of qualitative indicators such as “personal resiliency” and “high emotional intelligence.” While research continues to debate the degree of influence across such variables, few would argue that faculty are outside the scope of influence in student success. Student success is something that proponents of Complex Adaptive Systems Theory and Nonlinear Dynamics call a “wicked problem.” Wicked problems are not defined by their degree of difficulty but rather by the fact that they cannot be resolved by traditional problem-solving processes and solutions. For decades, we have treated the influence of faculty on student success as though it were a morbidity or illness within this wicked problem. If we can just find the right combination of professional development and working conditions with our faculty, and get it through collective bargaining, we’ll see the gains we need and desire in student success! Sound familiar?

Administrators continue to optimize class sizes, enrollment, and budgets while faculty and their representative bodies work toward protecting academic integrity and the working conditions required to sustain communities of inquiry. All the while, the outside world of work continues to embrace new ways of achieving competencies and skills that offer economic advantages to so many. We seek to hold a moral high ground of academic integrity and the social value proposition unique to higher education, at a time when technology and artificial intelligence push boundaries only described in science fiction not a decade ago. How can we preserve that integrity, foster communities of inquiry, increase economic relevance, and sustain if not grow enrollment in a post-pandemic world? Whatever bold approach your college takes, it should undoubtedly engage faculty. Perhaps part of the answer to the wicked problem of student success is to rethink it from the perspective of faculty success.

A new paradigm of faculty autonomy and dimensions of scholarship

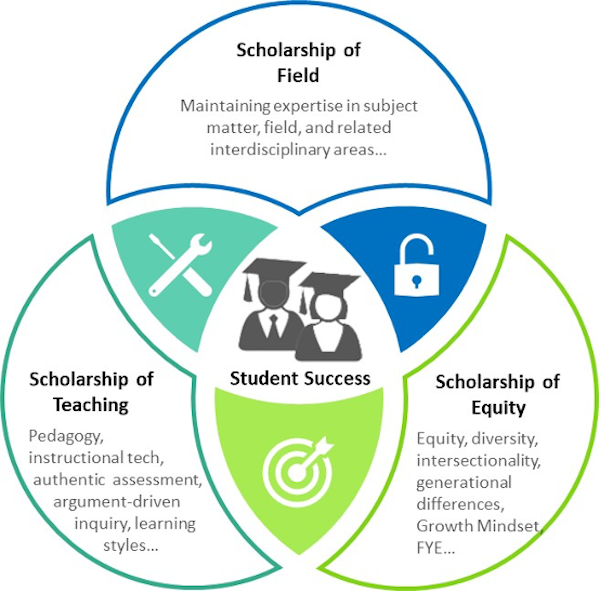

Valencia College set out some time ago to create what it envisioned as a new culture of faculty. In 2011, they were the first college to be awarded the Aspen Prize for Community College Excellence based on the strength of its graduation and transfer rates, especially among African American and Hispanic American students, as well as the high job placement rates of its workforce training programs. Clearly, this takes an entire college staff, faculty, leadership, and supportive community. When you look closer at this achievement, Valencia’s focus on faculty existed at the core of their targeted transformation. This focus on faculty is best pursued from the assumption that all faculty are practicing scholars across the dimensions that largely drive their world. Most faculty design, deliver, and assess learning opportunities often in addition to research duties and a long list of internal institutional and extra-institutional engagement efforts. We can think of the new dimensions of scholarship across what we teach, how we teach and who we teach.

These form the core dimensions of The Scholarship of Field, The Scholarship of Teaching, and The Scholarship of Equity respectively. If we empower faculty as active scholars researching and applying their ongoing findings to their teaching responsibilities, we inevitably run into the challenge of accountability. In my 30 years of service as an educator and academic leader, I have yet to meet a single faculty member unwilling to consider a new practice when they are treated as a scholar. Even those most perceived as “difficult” or “old school” came to the proverbial table and genuinely modified their practices when treated as scholars. I believe this is because at their core, each is a scholar.

Moving toward “activated collegiality”

This is the key point of this article. The very containers in which faculty are tasked to succeed are detrimental to student success. Course loads, class sizes, new technologies and a long list of core practices grounding financial models have created a culture of attrition across higher education. The rise in for-profit institutions and their focus on personalized services are now converging on proprietary data engines that anticipate student needs and curate individualized experiences. These next-level learning experiences combined with selfless customer service are forging new paths to personal and professional actualization. The way forward for public higher education exists along a similar path, enhanced by our community of scholars’ remarkable power.

Imagine a college where individual faculty have the autonomy to set their own class sizes, shift course modalities on the fly, adjust assessment methodologies mid-course, and craft their own loads. You may think such a system would evolve in self-serving fashion, as some indeed have, when exploring these practices. Now let’s add the layer of predictive analytics, content curated within learning management systems, and entire college cultures based on adaptive systems that drive funding allocations grounded in the one constant variable of student retention. In other words, we shift from older models of accountability governed through often contentious collective bargaining with the promise of activated collegiality. Such collegiality, like all scholarship, is highly governed by an allegiance of duty. The stewardship of that duty is clearly defined and consensually agreed upon by the practitioners themselves–the community of scholars. In such settings, we must remember that the definition of scholarship exists across the core dimensions of what we teach, how we teach and who we teach.

The absolute power of fusion teaching

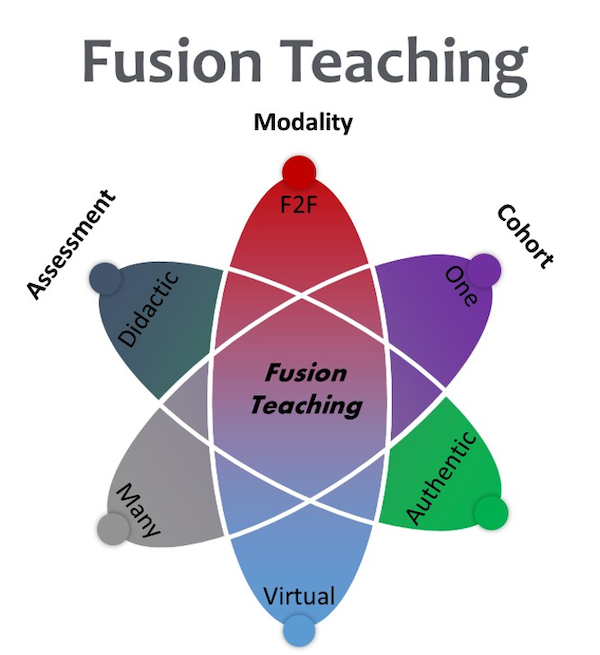

In our recent global pandemic, we learned the extent to which our faculty, institutions, and entire profession can adapt when faced with a challenge of unprecedented scale. We must note that our students, too, adapted across all categories. As we continue to learn in the aftermath of this challenge, we can clearly see that much of what we achieved occurred through fusing old practices and new. Some called it blended, hybrid, and other labels; I see this as fusion teaching.

Fusion teaching is the strategic combination of teaching and learning practices with the intentional design of physical classrooms, hybrid schedules, and course activities, increasingly grounded in faculty autonomy. It’s that last part of this model that excites me! Above all, fusion teaching empowers our faculty and adjuncts to adjust and adapt their preferred approaches based on student population characteristics and the preservation of high-quality learning outcomes.

This faculty autonomy, grounded in success and retention analytics, occurs across an interconnected spectrum. The adaptation, delivery, and assessment of fusion courses is guided by ongoing research in student success analytics and corresponding faculty practices leading to higher rates of retention and success. Fusion course shells serve as starting points in this model of maximum agility. The model is applicable to faculty and programs teaching a high variety of preps as well. Over time, courses can be broken down into grouped learning outcomes. Courses will become flexible and transparent as outcomes-based learning and artificial intelligence are combined and leveraged by faculty.

Faculty autonomy exists at the heart of this model. By empowering faculty with expanding options for course design, delivery, and assessment, we embrace a new era of scholarship and activated collegiality. The assurances of student retention and success follow analytics at the learning object level. It’s beyond the scope of this article to break down the continuums of modality, cohort, and assessment that comprise this model. The key aspect to take from it is not these components of design in the learning experiences but rather the degree of autonomy the faculty members are afforded in its ongoing and adaptive design.

Waiting for the pilot and data on fusion teaching?

Most institutions and leaders look to proven practices before allocating resources to pervasive models. Fusion teaching is a phrase I landed on following discussions with colleagues. It seemed to better fit the work our faculty were doing. We are all fusing together different pieces of strategies and approaches in hopes of improving our outcomes across higher education. At Broward College we are deep into the redesign of over 300 courses. We are addressing every learning object within those courses and curating their design directly with faculty. We hope next to attach predictive analytic engines to those learning objects. From there, we begin to mine and proactively assign specific objects to specific learners based on their profiles. This is the realm of metadata tags, knowledge grafts, recommendation engines and object performance efficiencies. We seek to expand this library of objects and empower our faculty and curriculum committees with the flexibility to group and re-group as desired. In this new world, we look toward recursive opportunities for students to better succeed. For example, imagine a student taking an accounting or economics class, and the system detects issues with core math skills, which then prompts the seamless embedding of math objects for the skills in that course, and for only that student. The possibilities are all but endless.

Jayden’s continued climb toward success

“Hello, Jayden,” said an alert from Professor Perez that she had pulled up on her phone during her break at work. “I just wanted to congratulate you on completing all learning outcomes successfully in your new cohort.” Jayden clicked and dragged the “Read More” link at the bottom of the message. “You have been a good steward of your opportunity to reboot your coursework. I am happy to see that you have enrolled in another one of my cohorts next term, where we will continue to expand your learning through the next sections of your portfolio,” continued the professor. “Let me know if you need anything in the meantime.” Jayden scrolled to the updated link on her degree progress, which displayed a new badge. There was also a new set of icons attached to her portfolio from even more prospective employers she had flagged following her progress. She began to text her mom the good news. “You’re up on table 12,” interrupted her supervisor. She smiled as she got up and left the breakroom.

This article is the second segment to a series. To read the first segment, click here.

Disclaimer: Embedded links in articles don’t represent author endorsement, but aim to provide readers with additional context and service.