Published on

Supporting Adult Students by Providing Flexibility and Resources

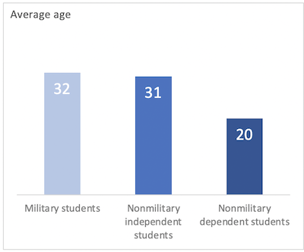

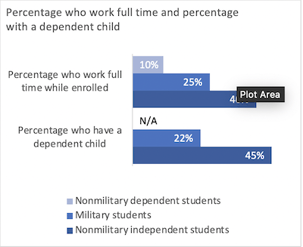

The American Institutes for Research, in collaboration with the Student Veterans of America, is conducting a study on the postsecondary experiences of student veterans.[1] Findings from the study uncovered many unique challenges that student veterans face as they pursue postsecondary education, but these findings also were a reminder that these students face challenges similar to adult students. As seen in these two charts, student veterans are similar in age and frequently have similar role conflicts as other adult learners, such as balancing jobs and families with postsecondary education. Several findings from our study point to supports and resources that could help not only student veterans but also adult learners more broadly succeed.

Across the United States, nearly 40% of students enrolled in American colleges and universities are over 25 years old,[2] yet student supports often are geared toward students between 18 and 24. This youth-centric nature of American postsecondary education is problematic for many adult learners because they often face unique challenges related to different life circumstances, including but not limited to financial independence, dependents, caregiving, non-traditional education, postsecondary enrollment delays, and full-time employment.

Research focused on adult learners has found that the commitment and effort needed as an adult student often conflicts with familial and professional roles.[3] In addition, the balancing act regularly required of an adult learner is compounded by feelings of alienation and isolation on a college campus that caters to younger students.

“We’re adults; a lot of our lives are different [from] normal students. Some of us have kids, and some of us have jobs, and it’s just very different.”

Student veterans reported the same issues in our study. They discussed juggling work, family, and other responsibilities while attending classes. For example, one student veteran stated, “We’re adults; a lot of our lives are different [from] normal students. Some of us have kids, and some of us have jobs.” In addition, student veterans feel that they have very different life experiences from some of their peers who went straight from high school to college. Student veterans talked about how they held jobs with high-pressure responsibilities, and these experiences made it harder to relate to younger students.

With competing demands, student veterans stated that flexibility, including online learning options and part-time coursework, was essential to helping them balance their coursework and lives. As one student veteran relayed, “I work two part-time jobs, I’m still in the military, and I have three kids. So, the more that I can take online and work at my own pace, the better.” Student veterans also reported feeling most supported when faculty and staff treated them like adults and were invested in their success. Faculty and staff helped demonstrate their support by understanding the competing priorities they juggled and offering flexibility.

Revisiting general education course requirements to account for prior learning as well as minor tweaks (e.g., extending academic counseling hours to support those with professional or family responsibilities), would help address student veterans’ and adult students’ needs for greater flexibility. Addressing childcare needs also would help military and adult students be more successful.

Studies similar to ours can shed light on the steps that postsecondary institutions can take to better meet the needs of student veterans and also align that research to adult students more broadly. Revisiting general education course requirements to account for prior learning as well as minor tweaks (e.g., extending academic counseling hours to support those with professional or family responsibilities) would help address student veterans’ and adult students’ need for greater flexibility.[4] Addressing childcare needs also would help military and adult students succeed more. One study found that college students with children were three times more likely to graduate if they had access to childcare.[5] Despite this result, there has been a recent decline in on-campus childcare options, with less than half of four-year public institutions providing it.[6] This situation underscores the importance of continuously revisiting university polices and supports to ensure that they provide options and resources to support adult students.

These early findings and lessons are based on focus groups with student veterans conducted in 2020. An upcoming report in spring 2021 will include findings from a survey of student veterans nationwide and will delve into experiences specific to them and student veterans of color in particular. To learn more about the study, please visit https://www.air.org/project/informing-improved-recognition-military-learning.

[1] In this context, student veterans are veterans and military service members on active duty or in the reserves who are pursuing undergraduate or graduate studies.

[2] See https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d18/tables/dt18_303.40.asp for more detailed statistics.

[3] See https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/2158244017697161 for more information.

[4] See https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/2158244017697161 for more information.

[5] See https://www.luminafoundation.org/files/resources/child-care-for-parents-in-college.pdf

[6] Eckerson, E., Talbourdet, L., Reichlin, L., Sykes, M., Noll, E., & Gault, B. (2016, September). Child care for parents in college: A state-by-state assessment. Institute for Women’s Policy Research. Retrieved from https://www.luminafoundation.org/files/resources/child-care-for-parents-in-college.pdf

Author Perspective: Analyst