Published on

How to Become the University of Choice for Veteran Students

While there are certainly a multitude of answers to this particular question, this article will focus on one of the ways institutions can act as assets in the integration of their student veteran populations.

In order to establish an environment that encourages student veteran academic success, institutions can begin to identify those services and agencies that best address this concern. Many institutions already have these help agencies and it’s a matter of leveraging those services to address a specific set of the student body. Of the requests made to my veterans regarding enrollment in universities, 62 percent of respondents identified veteran student services provided by the university as the greatest informational need. This outweighed the acceptance of credits earned during military service (50 percent), estimated student loan debt upon graduation (40 percent) and graduation rates (40 percent).[1]

The institutions that can address the specific need and support desired by veterans will be positioned to better recruit, retain, integrate and matriculate student veterans. By establishing a three-facet approach to veteran student services, institutions will become the university of choice for veterans returning to higher education.

Student veteran integration models will vary among institutions. However, the cornerstone for any success should be based on dialogue and mentorship. Using a three-facet approach, the institution develops a diversified campus footprint in its student body, and in the larger context of dialogue among varying viewpoints.

First, establishing a veteran student services office allows for the institution to link those services that it provides to a ‘one-stop shop’ for student veterans. Additionally, this institutional focus creates an environment a student veteran will feel more comfortable in. While this may seem redundant, it in fact acts as the first step in a long-term integration process. Within the veteran student service office model are three subsets. First, the director, who as a member of the staff, is able to address student veteran concerns and success stories at the highest levels of administration. Second, an ombudsman, whose primary focus is integrating the student veteran with the help agencies available on campus. Third, and perhaps most crucial to the success of student veterans, is the establishment of a student-led veteran organization. The primary focus for this group is peer support and mentorship. These three capabilities, working in concert, create the atmosphere in which academic success is most readily achieved.

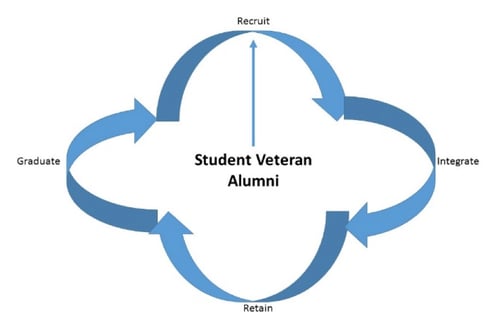

With a veteran student service office created, institutions are then able to create long-term success for their student veteran population. The ultimate goal for any student is to graduate. This goal also means the former student is now an alumnus. By identifying this as a crucial step in the integration process, institutions will reap the benefit of academically successful student veterans, who will recruit fellow veterans to their institution due to the positive environment and outcome of their educational plan (mapped out in Figure 1).

As members of the military begin to return to the classroom, the opportunity for colleges and universities to act as positive agents in the successful integration of veterans into the university has never been greater. Many of those returning to school are seeking to better themselves, and are focused on their goals. By identifying their needs and addressing them, institutions will find a student who is willing to work hard, is able to adapt to differing circumstances and will enhance the diversity of thought on the campus.

– – – –

References

[1] “VA Education Benefits: VA Should Strengthen Its Efforts to Help Veterans Make Informed Education Choices.” U.S. Government Accounting Office. US GAO, 13 May 2014. Web. 15 Sept. 2014. Accessed at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-14-324

Author Perspective: Student