Published on

The Competitive International Higher Education Marketplace: Identifying Business Strategies to Succeed (Part 1)

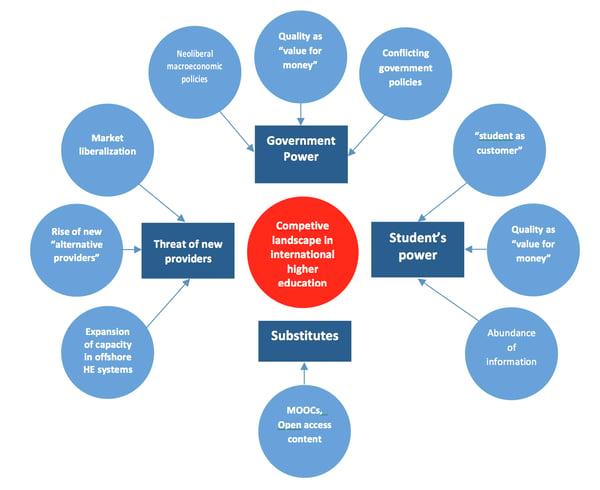

What’s obvious to everyone involved in higher ed is that, in the past decade or so, a new competitive landscape has emerged in international higher ed. This competitive landscape is shaped by a wide range of factors often neglected or considered separately. However, a comprehensive environmental analysis is required in order for one to be able to move on with any considerations and suggestion on future strategic directions for higher ed institutions.

One of the key factors that shape higher ed nowadays is the student. Since the 1990s, there has been a consistent manifestation in most of the developed countries — whose higher ed systems act as flagships for the entire sector (e.g. United States, United Kingdom, Canada and Australia) — about the concept of the student as a customer. This implies an increased focus of higher ed providers and external bodies to improve the student experience, which actually refers to service quality. As a result, students today expect more from higher ed providers, and universities try to offer more to their students.

At the same time, students are now encouraged — mainly by government bodies — to make value-for-money considerations when choosing a program and when evaluating programs after graduation. Another development that has impacted the bargaining power of students is the integration of new technologies that provide instant access to abundant information, which in turn allows students to inform their decision making with information not previously available. All of these have initiated a transfer of power from universities to students, and this trend is poised to continue in the future.

Higher ed institutions, and the sector as a whole, have been impacted and shaped by the macro-dynamics of the international economy. The adoption by most developed countries of neoliberal policies as a response to the world financial crisis meant a consistent decline in the proportion of direct public funding into higher education and its replacement with private. This has intensified the competition amongst higher ed institutions to develop alternative income streams while at the same time reinforcing the view of students as customers and quality as value-for-money. Immigration concerns in most destination countries of international students induced immigration policies that had a negative impact on the flows of inbound student mobility. This conflicted with calls for the need to invest more on expanding the presence of international students as a response to the declining public funding into higher ed.

The new competitive landscape in international higher ed is also shaped by a range of changes that impact the velocity of entry and the number of new entrants in the sector. At a national level, this neoliberal movement has led to the liberalization of the higher ed sector, where more private providers will have degree-awarding powers. At the international level, countries in Asia — which appear to be in a different phase of the macroeconomic cycle — have been able to invest in building the capacity of their higher ed systems. These capacity-building efforts have looked beyond the expansion of the supply and also focused on improving the quality and reputation of local higher ed systems. This means it could become increasingly difficult for western higher ed institutions to attract international students from these countries.

Another factor that shapes the intensity and the direction of competition in higher ed is the emergence of Open Access Resources (OAR) and Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs). There has been a lot of speculation about the impact of these developments on the demand for traditional higher ed but, so far, the evidence suggests nothing is changing dramatically. MOOCs have failed to secure their place in the formal higher ed sector primarily due to the lack of a sustainable monetization model. Also, the heavy focus by students on return on investment deters them from investing their study time into anything that does not lead to a formal degree that can then be used in the employment market.

That said, OAR and MOOCs absorb a significant portion of students who otherwise would have sought to attend professional development, lifelong learning opportunities or short courses offered by traditional higher ed providers. This has had a direct negative impact in the income of these providers, who relied on such offerings as their main alternative revenue stream. On the other hand, one can see the use of OAR and MOOCs as a “trial period” of the “real thing;” something that can potentially help universities participating in these initiatives to attract students to their traditional programs.

Conclusion

All the above describe the dynamics of the current competitive landscape in international higher education. To respond to this triad of challenges (1. declining public funding; 2. less prosperous prospects for the flow of inbound student mobility; and 3. increased competition at home and abroad) higher education institutions should think carefully of their international business strategy.

In the conclusion of this two-part series, Dr. Tsiligiris outlines how an international business strategy can help set institutions apart from their competitors and succeed in the highly competitive higher education marketplace.

Author Perspective: Administrator