Published on

Bring in the Translators and Decoders: The Language of Credentialing Needs Help – Part One

- Karen Elzey, Associate Executive Director, Workcred

- Deb Everhart, Chief Strategy Officer at Credential Engine

- Paul Gaston. higher education consultant with accrediting organizations, higher education institutions, and Lumina Foundation

- Amelia Parnell, Vice President for Research and Policy, NASPA

- Cynthia Proctor, Director of Communications and Academic Policy Development in the Provost’s Office, the State University of New York (SUNY) System

- Julie Uranis, Vice President for Online and Strategic Initiatives at the University Professional and Continuing Education Association (UPCEA)

Credential As You Go (CAYG) sponsored the virtual Summit on Language Used in the Credentialing Space: Big Concepts, Many Terms, Multiple Perspectives, Different Voices on March 16, 2022. The Summit focused on three troublesome areas of language use: Credentials and Pathways; Equity, Inclusion, Fairness; and Competencies, Skills, Learning Outcomes. The first three parts of this four-part series focus on these three areas, part four on key takeaways.

Holly Zanville (CAYG) and Julie Uranis (University Professional and Continuing Education Association) set the stage for the discussions. Zanville noted that many concepts and terms in the learn-and-work ecosystem are new to the field and have no established definitions. Many are trending terms and concepts, not well understood. Others are used in different ways, depending on stakeholder perspectives and contexts. CAYG prepared a draft document that focuses on the terms, concepts and context: “Definitions and Use of Key Terms in Incremental Credentialing.” Criteria were established to collect and select terms with the main aim of capturing diverse and nuanced voices from employers, research reports, college and university websites, media articles and blogs and dictionaries and glossaries. The document includes 73 terms among 42 term areas and 168 entries. Entries come from 61 different organizations or individuals.

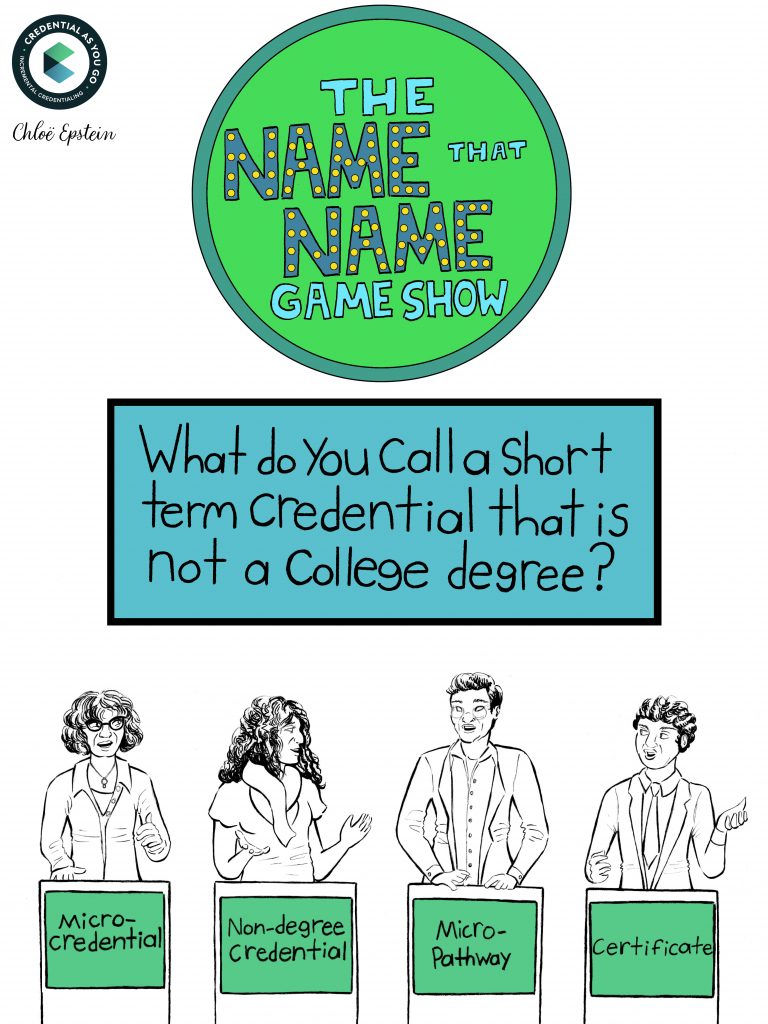

Zanville compared the current context to a game show, on which contestants are asked, “What do you call a short-term credential that is not a college degree?” Contestants answer micro-credential, non-degree credential, micro-pathway and certificate. They are all correct because more and more names in credentialing mean the same or almost the same thing. With all these synonyms, there is growing confusion for learners, employers, higher education institutions, policymakers, and many other stakeholders.

Julie Uranis chairs an UPCEA committee focusing on typology, terminology and standards. The committee has observed that this may not be the best time to lock in set definitions for particular terms given the flux in the marketplace and instead focus on bringing clarity and supporting particular terms and attributes without creating a specific definition for each one. One of UPCEA’s recommendations to member institutions is to consider a “continuum of credentials” in creating order and sense-making for their institution. The key is transparency: We can call these things anything we want as long as we define and contextualize them. So, what we call a short-term non-degree credential, whether it’s a micro-credential, badge or certificate, is not as important as declaring that it is a short-term non-degree credential. This description allows some cross-walking of these credentials until there is a common use of terms.

The Credentials and Pathwaysdiscussionwas moderated by Amelia Parnell (NASPA) with panelists Karen Elzey (Workcred), Deb Everhart (Credential Engine), Paul Gaston (higher education consultant); and Cynthia Proctor (SUNY System). The panel addressed this question:

With terms like badges, micro-credentials, micro-pathways, short-term credentials, incremental credentials, certificates, licenses, certifications, degrees and noncredit-to-credit, bridges becoming so confusing and are used in different ways. What are the key credential and pathway terms, who defines the terms, and where and how they are being used?

Paul Gaston noted that the proliferation of credentials has created too much choice for learners especially, a situation in which misjudgment can become likelier and risk outpaces benefits. The wealth of definitions of programs, credentials and even for disciplines−and certainly for terms−is an obstacle. There are over 300 varieties of the MBA, for example. The volume of choice creates major obstacles for the learners’ ability to navigate our higher education systems.

Gaston asked us to think of the different ways the term applied is used. For example, most people used to believe they understood what a doctorate degree is. But now there are many varieties, including something called the applied PhD, which seems to be a contradictive term. A term for a degree or other credential may appear familiar but can be deceptive. Is the new program that enables one to become a health coach have something to do with medicine? No, it has very little relation to that. So, figuring out what programs are about is increasingly complicated. He suggested three steps to address the problem:

- Appeal to the disciplines, so they achieve greater order and clarity within themselves. Some degree of standardization would not limit the schools’ ability to respond to emerging needs or compete effectively and would go a long way in reducing confusion.

- Identify the most misunderstood areas and work together toward resolving the confusion.

- Pay attention to learners who don’t have the benefit of well-qualified high-school counseling or informed conversation with peers. Every high school curriculum should be responsible for preparing learners to navigate the vast choice of credentials. Every college and postsecondary education provider should be explicit about its terms, what they mean and how learners can navigate the opportunities they make available.

Cynthia Proctor added perspectives from the State University of New York System of 64 campuses. Half the institutions are offering micro-credentials−over 400 micro-credentials in over 60 discipline areas, and activity is growing. Students can choose from the options by going to a dedicated system website that allows them to filter by topic and institution. It is an ongoing challenge for each campus to approach definitions consistently for information to be clear to learners and partners.

SUNY’s micro-credential work is grounded in a systemwide micro-credential policy adopted by a system-level board of trustees with authority over the academic programs at all campuses. Adopted in 2018, the policy includes a glossary of terms and a SUNY-specific definition of high-quality micro-credentials intended to help with language-related issues. It was clear early on that having a policy and a consistent definition of a microcredential would be important to avoid nomenclature madness—one of the biggest challenges initially was the use of the terms micro-credential and digital badge interchangeably. SUNY pushed for a definition of a micro-credential and a reframing of the way digital badges were thought of. They have come to understand the relationships using this phrase: diploma is to degree as badge is to micro-credential. There is growing recognition, including by New York’s Governor and State leaders, of SUNY’s definition of a micro-credential and its commitment to quality. SUNY is aware that there are still a range of interpretations. Nationally, a badge is used for everything from participation, to community-building and corporate training by many large companies. There are also questions about the distinctions between a certificate and micro-credential. In New York State, a certificate is defined under education law, so the SUNY policy had to be clear that a micro-credential is distinct from a certificate. In other states, many folks consider certificates to be micro-credentials. Any national taxonomy has to consider how state regulation/law/regulatory bodies are defining these terms. Proctor also recognized the growing use of the term non-degree credential. Since 67% of SUNY’s micro-credentials stack to a certificate or degree, she doesn’t want to lose the idea of micro-credentials as pathways to degrees. Recognizing micro-credentials as a distinct category of non-degree credentials, as New York has done now, is important.

Karen Elzey agreed there is nomenclature chaos and that it has an impact on employers as well. The chaos is exacerbated as each employer consumes information about different types of credentials with different names and meanings issued by a variety of higher education institutions and training providers. Also, employers struggle to differentiate the purpose of a credential and what it signals about the learner. For example, there is confusion about the difference between a certificate and certification. One of the biggest issues is helping employers better understand what’s behind a credential -in essence, what it qualifies an individual for and how that matches with the jobs available in their own firms. In conversations with manufacturing employers, some were unsure whether employees held particular credentials. While the hiring manager had more information about what credential a person held, there was still a lack of information about what the credential signaled and its relationship to the skills required for the job. There was also a lack of knowledge about whether the credential assessed competencies or measured the achievement of learning outcomes and how that related to job tasks.

The challenge of capturing what a credential measures is compounded by the fact that many employers offer training themselves, and in some cases that training is offered by third-party vendors. Often, the learning that occurs in that training isn’t really captured by the employer. That poses challenges for workers seeking to move to another job within their firm or move to another firm, since it is difficult to effectively document the learning and skills gained through the training. For example, when a manufacturing firm gets a new CNC (Computer Numerical Control) machine, typically there is some instruction provided by the vendor as part of the sales process. A person is learning new skills through this instruction, yet that information is frequently undocumented.

Definitions of credentials are important, Elzey noted, because they provide clarity. But with so many definitions, how will the information be captured using technologies such as blockchain or Learning and Employment Records (LERs)? The information must be in a format that allows employer systems to consume a myriad of information from different sources. When that happens, employers will benefit by having more complete information as they seek workers with the knowledge and skills to fill roles in their firms.

Elzey questioned the view that too many credentials and too much choice results in learners making poor choices. In other settings, people welcome choice (e.g., shopping on Amazon) though having those choices comes with more consumer risk. The larger issue with so many credentials is that it is difficult to judge their quality. The issue of exponential credentials and determining quality is a growing concern.

Deb Everhart agreed there is cacophony in the marketplace.Credential Engine is trying to address it by focusing on credential transparency through technology. Research shows there are over a million credentials offered just in the U.S. now. How does anyone make sense of all that and navigate through our systems well? Different types of definitions are useful for different audiences and purposes. Whether you’re a provider developing a credential, employer trying to make use of that credential, accreditor or other quality assurance provider, policymaker at the institution or system level, or state and federal governments, explicit definitions and a particular type of language will be needed.

Credential Engine has developed the Credential Transparency Description Language (CTDL) to enable machine-readable definitions. For example, many use the words certificate and certification interchangeably, which is a mistake because they are very different. One key difference being that certifications have to be renewed. That’s important for everyone to know. If you’re looking at that from a marketing perspective, you should at least let the learner know that this is something that needs to be renewed—it is not a lifetime, one-and-done credential like a degree. If you’re an employer, you need to know that certifications are often issued by industry bodies and know whether a certification is relevant for your industry or is required for legal compliance. Policymakers also need specifics in deciding whether to provide public funds for obtaining that certification or for renewing it or both. This is where the machine-readable CTDL can serve all those purposes because the definition (description of the credential and related information) is provided as linked open public data that connect many different data points. So, when you’re looking at that certification, you can see what competencies it includes, whether it is renewable, what occupation(s) it aligns to, the time to complete and more. Machine-readable data can help make sense of these many terms.

Key takeaways

- There is nomenclature chaos in credentialing that impacts many stakeholder groups: learners, employers, higher education institutions, accrediting bodies and policymakers.

- This may not be the time to push for consistent definitions, as the space continues to evolve. For now, we can call these things anything we want as long as we define them, put them into context and focus on transparency.

- The proliferation of credentials, when you look at the growing number of degree types and non-degree credentials, could be argued as providing too much choice for learners. This is a situation in which misjudgment can become likelier and risk outpaces benefits. We have to support informed selection and ensure risk does not outpace benefits.

- With the proliferation of credentials comes the imperative to judge quality.

- A strong policy play, like the SUNY System’s, can help to reduce these language issues as micro-credentialing practice grows.

- Employer training can provide complications if the learning (skills/competencies) is not documented. Employer partnerships with higher education institutions can help mitigate this issue.

- Using technology to inform credential attainment (e.g., through blockchain or Learning and Employment Records [LERs]) requires that education and employer systems use machine-readable data in open standard data structures like CTDL. Linked open data systems can help to reduce or eliminate the cacophony in credentialing language.

The discussion on the challenges of language use in credentialing will continue in Part 2’s focus on Equity, Inclusion and Fairness.

Author Perspective: Administrator