Published on

How Is the Learn-and-Work Ecosystem Like an Ecological Ecosystem—And Why Does This Matter?

The term ecosystem is increasingly used in discussions about learning and work. For instance, two national initiatives—Credential As You Go and the Learn & Work Ecosystem Library—are framing their work as an effort to improve the learn-and-work ecosystem. Also, Noah Geisel at the University of Colorado Boulder recently chose a relevant theme for his university’s badging conference in summer 2024: not “it takes a village,” rather “it takes an ecosystem.”

Despite the growing understanding that our systems of education and employment do indeed comprise of an ecosystem, that term is still more commonly associated with natural, biological systems than with social ones. Are they the same thing? And does the answer to that question really matter? I have come to believe that they are very similar—and yes, it does matter.

Ecological Ecosystems

In his report “Ecosystem and Its Components”, Professor A. Balasubramanian, from the Centre for Advanced Studies in Earth Science at the University of Mysore in India, defines an ecosystem as an environment that includes living organisms and their inseparable, interrelated, nonliving physical conditions. The resulting environment is a self-sustaining, structural and functional unit. It may be natural or artificial (human-made), land-based or water-based. Examples of artificial systems include croplands, gardens, parks and aquariums.

Ecosystems come in many sizes and types—from a large forest to a small pond. They can be separated by geographical barriers, as are deserts, mountains and oceans. They can be isolated like lakes or rivers. Ecosystems receive energy from an outside source (the sun), use that energy and ultimately release it into space.

While ecological ecosystems have borders, they tend to blend into each other; their borders are not rigid. In a healthy ecosystem, organisms are well balanced with each other and with their environment.

Many things can create unhealthy, unbalanced ecosystems, including environmental changes or the introduction of new species. Some changes can have disastrous results, causing the collapse of an ecosystem and the death of many native species. Some changes can also promote the ecosystem’s natural evolution to make it more resilient and flexible.

The Learn-and-Work Ecosystem

This leads us to the “So what?” questions: Is the learn-and-work ecosystem like an ecological ecosystem? If so, does it matter?

The learn-and-work ecosystem is much like the ones we find in nature. Those working to improve the learn-and-work ecosystem and those who depend on it to meet their educational and career needs can both benefit from understanding how ecosystems work.

For any ecosystem to thrive, its interrelated components must be well balanced. What then are the components of the U.S. learn-and-work ecosystem?

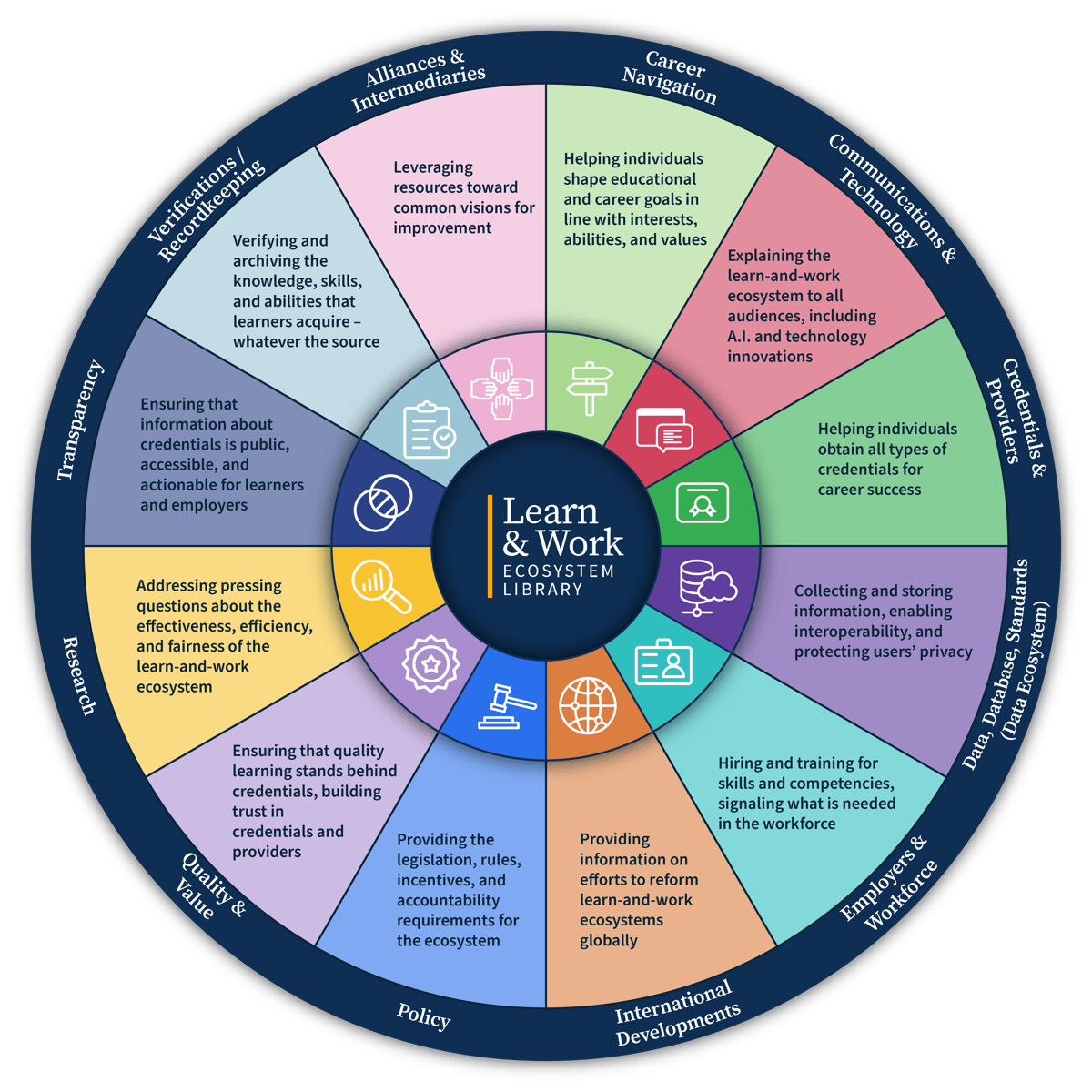

The Learn & Work Ecosystem Library, which launched in 2022, defines the learn-and-work ecosystem as a connected system of formal and informal learning (education and training) and work. Although others may define the ecosystem in different ways, the library makes the case that the ecosystem features twelve important building blocks or components that are depicted in this wheel graphic:

These twelve components must be connected and coordinated so that:

- Individuals can move seamlessly through the learn-and-work marketplace using a variety of credentials to communicate the skills and knowledge acquired in multiple settings (school, work, service, self-study)

- Schools can count learning obtained outside academic settings toward a degree or other credential

- Employers can have more detailed and externally validated information for hiring, reskilling and upskilling workers

- The public is informed about the learn-and-work ecosystem

Just as in an ecological ecosystem, not all components in the learn-and-work ecosystem are the same size or character. Still, all components are related. The ecosystem falters when components work in silos; their borders need to be penetrable to facilitate interdependence.

There are many special projects and organizations working to improve the various components of the learn-and-work ecosystem. Many—perhaps most—focus on just one or two components, such as improving credentialing or aiding career navigation. But the reality is that the ecosystem will not thrive unless all components function well and recognize and support the other components of the ecosystem.

Is there a master ecologist to direct and manage improvements to the learn-and-work ecosystem? In the U.S., there is no national manager comparable to those in some other nations (for example, national agencies or ministries that assess the credential outcomes and employment conditions). The U.S. ecosystem is decentralized, complex and often siloed, which makes our ecosystem difficult to understand, navigate and improve.

And what happens when innovations come to the learn-and-work ecosystem—like a new animal or plant species entering a natural environment? This is precisely what is occurring. We’re seeing a range of new arrivals: badges, industry certifications, digital platforms, third-party providers, applicant-tracking systems for employer hiring. All these innovations—and countless others—are disrupting our traditional degree-centric postsecondary education system. Innovations in skills-based training and hiring are prompting more and more employers to abandon traditional practices and move to systems that judge job candidates on their competencies and skills.

As stewards of the ecosystem, are we watching to see if these innovations cause harm as they disrupt our traditional higher education and hiring structures? Or could these innovations function like natural selection evolving the ecosystem? Can we accommodate and indeed welcome these changes as improvements to the system?

If you visit the Learn & Work Ecosystem Library, you will see that it captures a picture of an ecosystem in which all parts are related and interdependent. The library is a web-based, wiki model library that collects, curates and coordinates resources to support the learn-and-work ecosystem. Typically, library searches for information about a new project will show that it falls, not in just one ecosystem category but within several of the twelve components listed above.

As more innovations and disruptions are bound to occur in each of these areas, let’s consider whether the learn-and-work ecosystem can manage disruption better than a natural system and be flexible and evolve like some natural systems. Ecological systems typically require time for adjustment—often generations of genetic change and adaptation.

But our human-made learn-and-work ecosystem can and should change rapidly, so long as we set into motion an evolution of policies, practices and processes to support improvements in the ecosystem and mutually agree that these changes are needed to give the ecosystem resiliency.

This is what many are working toward—a healthier, well-balanced, and fairer 21st-century learn-and-work ecosystem that works for all Americans.

Whether you are a credential provider, an educator, an employer, a journalist trying to explain our system to learners or a policymaker trying to invest in solutions to improve our systems, there should be no doubt that we function in a shared learn-and-work ecosystem. We can and will stay in our respective lanes of change, but we must know that we are interdependent with many other components of the ecosystem and act accordingly to support each other. We must step forward as the new ecologists of the U.S. learn-and-work ecosystem.