A Systems Approach to International Enrollment: Identifying and Overcoming Six Prevalent Myths

Enrollment management is a large and complex system comprised of interconnected parts. These parts include recruitment, admissions, academic advising, student services, alumni relations and so on. When all pieces are working in unison, the institution is better able to achieve its enrollment goals. However, when individual components operate independently of each other, then overall effectiveness and efficiency is greatly reduced across the entire system. In the very worst cases, one or more parts work against the others causing unavoidable failure.

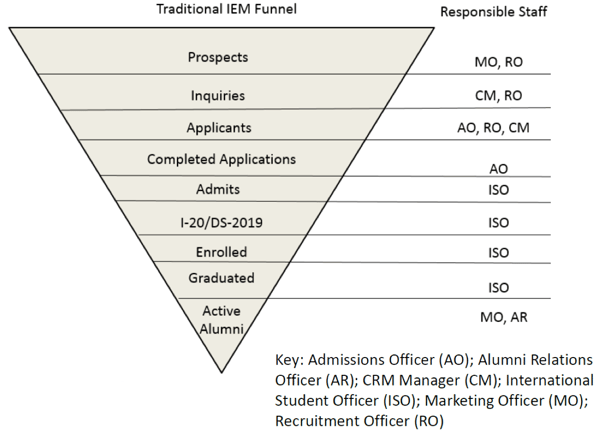

Strategic international enrollment management is defined as “a focused and holistic strategy involving the successful recruitment, admission, enrollment, retention, graduation, and reentry of international students translated into an operational plan.”[1] It includes all aspects of the traditional enrollment funnel with a few additions (e.g., acquisition of appropriate immigration documents).

While international enrollment management is often considered to be a subsection or specialty area of enrollment management, it is actually the opposite that is true. International enrollment management encompasses not only domestic, but also global patterns and trends. This article introduces five common myths about international enrollment management. Each section concludes with a statement of how systems thinking can help to dispel the myth and resolve the associated problem.

Systems Thinking

Before getting to the myths, it’s worth providing a brief overview of systems thinking and its application to international enrollment management. Peter Senge defines systems thinking as a discipline for seeing “the interrelationships rather than the linear cause-effect changes, and seeing processes of change rather than snapshots.”[2] From a conceptual standpoint, systems thinking aids strategic planning for international enrollment management by enabling leaders to focus on how to effectively implement desired changes with minimal amounts of effort. As such, plans tend to be more ambitious, more inclusive and more achievable. Systems thinking is a valuable tool for strategic planning because it shifts the focus of analysis from distinct parts (e.g., recruitment, admissions and housing) to include interactions and interdependencies among parts. This is helpful for conducting thorough analyses of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats.

A common error made by campus leaders is failure to apply systems thinking to enrollment management. As such, enrollment management is often approached as a collection of disparate parts including, but not limited to, recruitment, marketing, admissions, orientation, career advising, academic advising, registration, housing, etc. In all too many instances, international student recruitment, admissions and services are additional parts forced to fit into the larger whole. Each part is assigned unique individuals responsible for their own area, but not necessarily responsible for, or even aware, of others. Systems thinking forces individual contributors and campus leaders to see beyond the individual parts in order to consider interconnections, and to understand how a change to one part of the system affects the whole. In so doing, systems thinkers are able to anticipate and prevent unintentional consequences, such as spending a small fortune on purchasing leads for an intensive English program only to discover the institution’s CRM is unable to send messages with non-English characters.

Myth 1: International Enrollment Management is Separate from Enrollment Management

The first myth is one that is perpetuated by the administrative structure at many colleges. It is fueled by an assumption that domestic enrollment and international enrollment units need not collaborate nor communicate when they fall within different divisions of the university. In most instances where this is the case, domestic enrollment management staff fall under divisions of student affairs or enrollment management while international enrollment management staff fall under divisions of international affairs or academic affairs.

It is important to note that many elements of enrollment management apply to domestic and international students alike. At a conceptual level, this includes an emphasis on successful recruitment, retention and graduation of students in accordance with an institution’s academic mission, vision and goals. At a practical level, this includes the provision of essential information about the institution, its academic programs and community in which it is based, instructions for completing an application for admission, clear communication, feedback and support throughout the admission and enrollment processes as well as assistance managing transactional issues, such as course enrollment and tuition payment.

The systems challenge posed by this first myth is to recognize how administrative structure influences behavior and work to leverage shared goals in order to encourage desired changes, such as cross-divisional strategic planning and resource sharing.

Myth 2: Global Access to Standardized Testing Facilities

The second myth pertains to access and it is perpetuated by a tendency to minimize cultural, political, economic and other differences across nations. This myth is the basis of requiring standardized test scores from international applicants for admittance to undergraduate or graduate programs without considering whether or not testing facilities actually exist or are accessible within the applicant’s country of residence.

The systems challenge this myth presents to campus leaders is to discover the circular nature of cause-and-effect relationships embedded within the enrollment management system.[3] In this case, requiring standardized tests from applicants who cannot take the tests in their country creates barriers to access that inevitably reduce the diversity of the international student body and limit an institution’s ability to truly engage globally.

Myth Three: Foreign Educational Credentials Are Domestic Transcripts in Disguise

The third myth pertains to foreign educational credentials, which are often handled by untrained or undertrained faculty and staff. As educational systems vary substantially from country to country, it is important that any foreign credentials received are evaluated by a competent credential evaluation specialist. A trained evaluator not only knows whether the credential is authentic, but such a professional can also determine the accreditation/recognition status of the issuing institution within its home country, convert grades or marks to a 4.0 scale, and apply a consistent conversion factor to any credits earned.

The systems challenge this myth poses to campus leaders is to consider how worldview limits and even warps understanding of reality. As such, admissions officers and faculty seek to meet an impossible standard of equivalency when the goal should be to assess admissibility within culturally relative terms. As a practical note, it is not unusual that certain stakeholders welcome assistance in evaluating foreign credentials, while others view a systems approach to credential evaluation as additional bureaucracy resulting from unnecessarily abstract notions about applied comparative education.

Myth 4: What Works Domestically Will Work Internationally

The fourth myth pertains to the assumption that the same marketing materials, websites and recruitment tactics are effective all across the globe. As a result of this myth, it is not uncommon to find campus leaders who invest heavily in international recruitment travel while ignoring the fact that their recruitment staff are uninformed of local cultural norms, their brochures reference information not relevant to international applicants and their websites includes photos that are offensive or misleading within the target market. While staff members eventually learn from their mistakes, new staff members are destined to repeat these errors so long as the myth is not addressed.

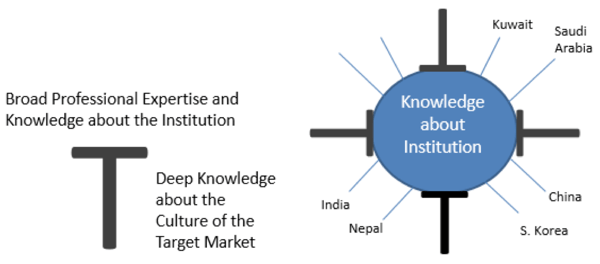

A training concept I’ve used with recruitment staff is that of a “T” model where the horizontal line of the “T” represents broad knowledge about the institution and its academic programs while the vertical line of the “T” represents a deep understanding of the market in which one intends to recruit. This concept can be made practical through the use of a program such as MS OneNote where a “Notebook” is created for a particular recruitment territory and staff fill in various sections pertaining to mobility trends, popular academic programs, commonly asked questions, travel logistics, key contacts, etc. This is a practical way of documenting both challenges and solutions so as to ensure such learning need not be repeated by new hires. From a systems standpoint, this practice allows us to make connections and share knowledge among staff so as to support the development of a learning organization. Peter Senge defines a learning organization as “organizations where people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire… and where people are continually learning how to learn together.”[4] Below is an illustration of this concept.

Myth 5: Faculty and Staff Are Prepared to Serve International Students

The fifth myth is especially troubling because it has a direct impact on the quality of the student’s campus experience, which can have negative effects on international student retention. According to this myth, faculty and staff are prepared to engage in the international dimensions of their academic and professional domains and, therefore, do not require any form of professional development, education and training programs that would better enable them to serve students from culturally diverse backgrounds.

Research indicates three major factors that should debunk this myth:

- A majority of international student advisors approach cultural difference from an ethnocentric perspective.[5]

- Most student affairs administrators are underprepared to serve international students.[6]

- Faculty are unlikely to act independently in addressing concerns related to international students in the classroom.[7]

The systems challenge posed by this myth is effectively employing leverage points in an effort to create ripples of change within and across related systems and subsystems. This may be accomplished by offering customized education and training programs focused on developing international awareness and intercultural communication skills.

There are many tools, resources and models available for designing training and education programs. For instance, I have used the Intercultural Development Inventory with more than 200 individuals to assess how they approach cultural difference and develop customized plans for further developing intercultural competence. I have also used intercultural simulations with students, faculty and staff to promote affective learning and empathy towards the challenges faced by international students. In my experience, such programs not only help the participants think about international students and intercultural adjustment more deeply, but they often bring organizational change by establishing much needed advocates within participating academic and student services units.

Myth 6: The Definition of “International Student” is Universally Understood

The sixth and final myth presented in this article pertains to the definition of international students. While this may seem like a straightforward issue, the fact is that international students are defined differently both within and across institutions. For instance, does “international student” include individuals who are undocumented, benefitting from deferred action, hailing from US-trust territories or granted political asylum? Does the institution’s definition align with that of the Institute of International Education, UNESCO or another organization? Does the institution define a foreign student separately? If so, how does a foreign student differ from an international student?

The systems challenge presented by this myth is one of accuracy and consistency. It is important to have a conversation not only with the international student office and enrollment management staff, but also with the institutional research team to determine what, if any, data standards are applied to international student records in the institution’s student information system. It is equally important to find out which staff members are charged with maintaining these records, how they are trained and who, if anyone, is continually checking the system for errors.

Systems Thinking is a Framework for Solving Complex Problems

Similar to the larger system of international education, international enrollment management constitutes a “fragmented, complex, multidimensional, interdisciplinary, intercultural field.”[8] It is a system that is impacted by the slightest changes at the campus level, but also heavily susceptible to international and global events. Systems thinking is a non-traditional, and perhaps abstract, framework for increasing understanding of challenges pertaining to international enrollment management, but its ability to dispel the six myths presented in this article is very real.

– – – –

References

[1] Aw, F. & Levinson, E. (Fall 2012) Evidenced based approach to strategic international enrollment management, IIE Networker Magazine. Fall 2012, 27-29.

[2] Senge, P. (2006). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. New York, NY: Doubleday.

[3] Waters Foundation, Systems Thinking in Schools, www.watersfoundation.org

[4] Senge (2006)

[5] Davis, J. (2009). An empirical exploration into the intercultural sensitivity of foreign student advisors in the United States: The status of the profession (Doctoral Dissertation). Boston College, Chestnut Hill, MA

[6] Di Maria, D. (2012). Factors affecting views of campus services for international students among student affairs administrators at five public universities in Ohio (Doctoral Dissertation). University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

[7] Cao, Y., Li, X., Jiang, A. & Bai, K. (2014). Motivators and outcomes of faculty actions towards international students: Under the influence of internationalization. International Journal of Higher Education. 3(4), 49-63.

[8] Mestenhauser, J. (2006). Internationalization at Home: Systems challenge to a fragmented field. In H. Teekens (Ed.), Internationalization at Home: A global perspective (pp. 61-78). The Hague, The Netherlands: NUFFIC.

Author Perspective: Administrator