Published on

Personalizing the Hispanic Student Experience Through Data Disaggregation: Implications for Fall Semester Preregistration and Long-Term Success

Recently, the Chronicle of Higher Education hosted a virtual event called “The Future of Minority-Serving Institutions” during which four panelists discussed the impact of COVID-19 on their institutions and how they innovated to better serve students of color and support their success. One of the panelists, Deborah Santiago, CEO and co-founder of Excelencia in Education, noted the importance of meeting students where they’re at and being aware of their needs, as they prioritized their families, economic situation, multigenerational status and, in some cases—when parents were no longer able to be employed—their responsibilities to work to support the family. In an earlier Chronicle essay, she also emphasized the critical role of family in supporting Latino student success but noted that when a student is the first in her family to attend college, the family’s limited knowledge of the college process can serve as a barrier to degree attainment. In a video statement on the Excelencia website, she calls for institutions to disaggregate data and drill deep to better understand how Latino students are performing and reveal opportunities for actionable efforts that can be taken to make sure they graduate.

Disaggregating data and identifying patterns unique to Latino or Hispanic students is one way of personalizing their educational experience. In discussing personalization, Kristin Bilodeau describes the ideal student experience as one in which institutions know who they’re talking to and get students what they want when they want it. The same could be said of getting students what they need when they need it. Two-thirds of first-generation students at Texas Woman’s are Hispanic. The information needs of these students may differ from those of non-Hispanic students due to the lack of a college-experienced support group at home. Data disaggregation is a simple and effective technique to help us better understand the dimensions of these needs, so we can better tailor appropriate and meaningful actions.

A first step in helping make the Hispanic student experience more ideal is ensuring that Hispanics get preregistered for an appropriate number of credit hours to stay on a productive path toward degree completion.

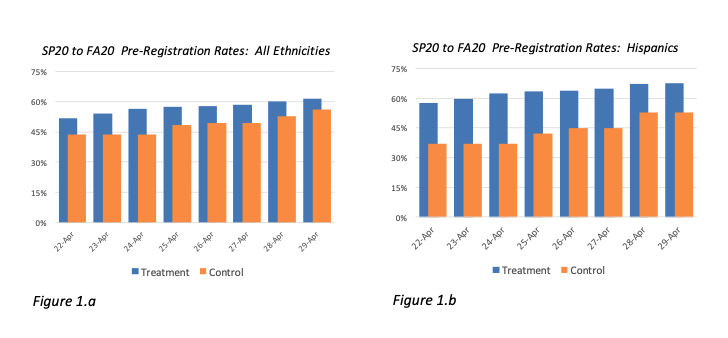

In Spring 2020, when the pandemic caused major disruptions nationwide and we were uncertain about its effects on Fall 2020 registration, we starting tracking preregistration rates more closely, looking for opportunities to intervene with appropriate information and actions. On the first day of preregistration for freshman, who were less experienced with the process, we sent a text to 80 percent of the group informing them that preregistration was open. The remaining 20 percent served as a control group. Then we tracked daily preregistration rates. We found there was a small but statistically significant daily difference between the treatment and control groups that lasted about a week (Figure 1.a). By the eighth day, and for the remainder of the semester, the daily difference between treatment and control had narrowed and was no longer significant.

It would have been easy to dismiss the texting intervention as having little or no effect past the first few days, especially if we had only reviewed the results at the end of the tracking period. But data disaggregation revealed a different story.

It turns out there was a huge and statistically significant gap between Hispanic students who received the informational text and those in the control group who did not (Figure 1.b). After the first day, the difference between treatment and control was 20.7 percent, which expanded to 25.5 percent by the third day. After the eighth day, when the overall gap had narrowed to the point of statistical insignificance, there was still a significant 15.1 percent difference between the Hispanic treatment and control groups. In fact, for those first eight days, the only daily difference was due to Hispanic students. There was no difference at all between the non-Hispanic treatment and control groups. This finding speaks to how first-generation Hispanic students, possibly lacking a knowledgeable support group at home, may need extra information on navigating the college system. Given additional guidance, they responded. Without it, they lagged behind.

You might be thinking, “It’s only a week difference, what’s the big deal? They’ll register later and catch up eventually.” The reality is that even a week difference could have a huge impact on longer-term persistence, which is essential for degree completion.

Researchers at The Center for Student Analytics at Utah State University found that earlier course registration is a much better predictor of student success than traditional measures such as high school GPA. Specifically, they report that persistence for high school students with low GPAs who registered when registration first opened was 8.7 percent higher than for those who registered right before the start of classes. The same was true of students with high GPAs, with early registrants out-persisting their late registering counterparts by 6.2 percent. These differences may be due partly, they note, to the better selection of classes available when registration first opens. This difference could be particularly important for Hispanic students balancing work and family responsibilities while attending college and needing to fit courses around their expanding work schedules.

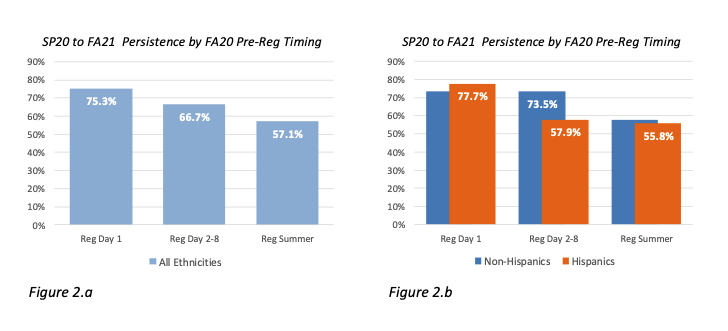

We took Utah State’s basic principle and applied it to analyzing the longer-term persistence of the freshmen involved in our Spring 2020 texting experiment, but we disaggregated by ethnicity instead of GPA. The results were similarly revealing and quite stunning. Overall, we experienced the same phenomenon as reported by the Utah State team. The longer-term persistence rate (SP20 to FA21) for freshmen who preregistered for FA20 on the first day was 75.3 percent, compared with only 66.7 percent for freshmen who preregistered on days two to eight—a significant difference of 8.6 percent (Figure 2.a). For those who waited until the summer to preregister, persistence dropped even lower to 57.1 percent.

These findings alone would be reason enough to take action, but once again data disaggregation tells a more dramatic tale in the case of Hispanic freshmen. The longer-term persistence for Hispanic freshmen preregistering on the first day was 77.7 percent—no different statistically than for non-Hispanic freshmen (Figure 2.b). However, for Hispanic freshmen preregistering on days two to eight, persistence plummeted to 57.9 percent—a significant difference of almost 20 percent. By comparison, there was no difference for non-Hispanic freshmen who preregistered a week later versus on the first day. Waiting until summer to preregister was similarly detrimental to both groups, with Hispanic persistence dropping to around 56 percent.

It remains to be seen whether this phenomenon holds true for the longer-term persistence of Spring 2021 Hispanic freshmen, who we’re also tracking. But for now, it serves as no-harm actionable insight on the behavior of our Hispanic students that can help us serve them better through interventions that address the preregistration issue. Essentially, the date of preregistration for a coming term becomes a leading indicator for persistence beyond that term. Through data disaggregation, we learned that Hispanics may have a narrower window than non-Hispanics before later preregistration starts to have an adverse effect on their long-term success.

This dramatic difference heightens the urgency to advise Hispanic students with sufficient lead time, so they can preregister on the first day. We intervened in Spring 2020, but we now know the texts arrived too late to be most helpful. In the spirit of continuous improvement, given new findings from our ongoing experimental research, we can adjust the timing of text messages to be sent this spring. But how soon is enough? Obviously, we need to allow enough time for students to schedule advising appointments and develop appropriate schedules for Fall 2022 classes. But we also need to consider Deborah Santiago’s observations on the role of family in the educational process and the added demands students may face due to the pandemic. Hispanic students may need additional lead time to discuss with their families how many courses they can afford to take while balancing their work and family responsibilities. Sending informative texts six or seven weeks before preregistration opens may be appropriate, even necessary.

Returning to the first step noted above, we’ve learned through data disaggregation that Hispanic students respond well to timely texts that offer extra information about how to navigate the college system, and they have a narrower window of opportunity before delayed preregistration starts to impact their long-term success. These two findings have helped us adjust our tactics to better personalize the educational experience for Hispanic students and help them stay on a more ideal and productive path to degree completion.

Author Perspective: Administrator