Published on

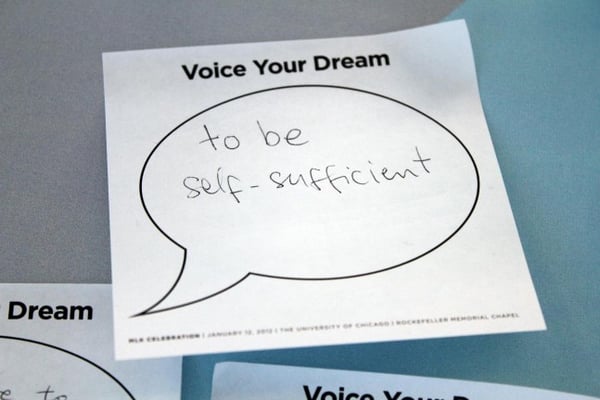

Self-Sufficiency And Programming

The following is the first of a two-part Q&A with UC Davis Extension Dean Dennis Pendleton. This first installment discusses how the Extension’s self-sufficiency affects its academic programming. We touch on the Extension’s support system, how shifts in state funding affected program offerings and how academic managers stay on top of their subject areas. The next piece will discuss the approach UC Davis has taken to establishing and maintaining its roots in the community. Look for Part 2 next Friday!

How does UC Davis Extension’s self-sufficiency affect its program decisions?

To elaborate on the self-sufficiency, we are totally self-supporting, meaning that we cover all staff, program, operational and facilities expenses as well as costs associated with any resources or services provided by other units of UC Davis. At this point given the state of the State’s budget we are also making additional financial contributions in support of the university. This is just as it should be given that we are fundamentally a part of the academic mission of UC Davis. So we’re totally self-sustaining and in addition contributing to the overall financial wellbeing of the university.

This affects our decisions in that every department is expected to cover all its costs. We’re explicitly a non-profit unit within the context of the university administrative framework. Vital and sustainable non-profit operation means that we need some marginal revenue to keep in a prudent reserve and also to have a capacity to invest in new things. A positive financial balance beyond full cost recovery need not be large but it is very important.

Self-sustaining operation affects programming decisions in that the academic managers of our programs need to not only look at educational needs in communities we serve as well as ensuring the academic quality of programs, but also must determine if there is an adequate market for the program to cover its full costs.

If we’re serving an audience that we think cannot cover the full costs of a program there are ways to bolster financial support. We have foundation grants, for example, and we have programs that we do in partnership with professional associations and with campus faculties and departments that enable us to underwrite programs that are not capable of recovering full costs via open enrollment fees. Also, a significant part of our annual self-supporting revenue comes from contracts and grants with both public and private sector organizations.

There was a time when continuing education in the University of California received some State support, but this changed in the late 1960s. At a point when there was some State support, continuing and professional education units had a little more flexibility in creating so-called ‘public programs’. Continuing and professional education is now largely focused on professional development—in a lot of different disciplines; that is, educational programs that contribute to individual professional growth and address organizational missions.

How can a school ensure its professional development and training courses are meeting the expectations of the client?

We rely on working professionals as well as highly-knowledgeable, highly-regarded faculty on campus in creating educational programs. Assessing educational needs and developing programs to address them in collaboration with our clients and partners is the very best way of knowing whether expectations will be met, because you’re engaged with them all along the way in creating the program.

We also do a lot of very specific market research in developing new programs. We work not only in contract and grant-supported work but also open enrollment—programs that we offer for working professionals in many different disciplines.

In creating a new line of programs we do a lot of market research, both survey research but frequently focus groups and consultation by program managers with key individuals in networks in a particular area; e.g., health sciences or law or land use or business and leadership. All of our academic managers have an effective network of contacts in their discipline. One of the most effective kinds of market research is connecting with folks who work in that area, informally sometimes and sometimes with surveys and focus groups.

These practices are very similar to what other continuing education units, I’m sure, do—market research that can be through electronic means or through mail surveys and focus groups and those sorts of things. In addition, though, when you’re doing contract work that’s based on organizational partnerships, there is an advantage in meeting expectations because you can be fully engaged with partners in the ongoing development and delivery of a program.

Tune in next week for the second part of our Q&A with Pendleton, focusing on UC Davis’s approach to relationship-building in the community.

Author Perspective: Administrator