Published on

Considering a Public Private Partnership? Realities and Opportunities in Today’s Higher Ed Business Practices

The economic and political imperatives that drive the complex nature of higher education today have introduced a new paradigm of management reform with a contemporary focus on efficiency and quality. Although touted by many as a new phenomenon, Public Private Partnerships (P3) have a long history dating more than a decade in the United States.

In the wake of the 2008 economic recession and the current public scrutiny regarding the cost of higher education, P3s have taken on a new meaning and have become part of a daily conversation by many universities seeking to achieve their strategic goals.

P3s are increasingly being used strategically, allowing institutions to offset fiscal pressures while exploring bold and innovative ways to diversify assets and expand services to support cost reductions, maintain and build new modernized academic facilities and develop support infrastructures that promote academic success (Gilroy, 2013).

Public Private Partnership Defined

In the most simplistic terms a Public Private Partnership is:

“a cooperative venture between the state and private business” (Lindher, 1999, p. 35).

While the Commission on UK Pubic Private Partnerships defines it as:

“risk sharing relationship based upon an agreed aspiration between the public and private sectors to bring about a desired public policy outcome.” (p. 35)

However, for the purpose of this discussion the Canadian Council for Pubic Private Partnerships provides a more suitable definition:

“cooperative venture between the public and private sectors, built on the expertise of each partner that best meets clearly defined public needs through the appropriate allocation of resources, risks, and rewards.” (p. 35)

Here, emphasis should be placed on the term “partnership,” which is the catalyst for mutual understanding and an explicit requirement given the complexity and diversity of the various entities seeking to do business.

Theoretical Underpinning

The complex nature of P3s is best understood by understanding system theory, which describes the relationship between various entities and their interconnected parts which are organized in such a way that they achieve a specific function for a particular reason (von Bertalanffy, 1976).

Therefore, it is imperative to view a P3 as a holistic and interrelated subsystem of the institutional community with a potential of directly impacting the student experience, and therefore it should not be seen as a single linear relationship or opportunity to reduce cost. From this theoretical perspective we can then operationalize “partnership” as an active participation from each sector (public/private) requiring each to adopt characteristics and viewpoints which once defined the counter parts identity (Linder, 1999).

It should be noted that the term partnership is a derivative of the retreat from the more conservative viewpoint of privatization and has served a strategic purpose in today’s ever-changing political climate. A partnership, no matter the size or reason, should be regarded as a pivotal act and careful attention should be placed on the alignment of mission and financial expectations to ensure mutual understanding and collaboration between parties (Oblinger, 2012).

Higher Education and P3s

P3s continue to change the context in which higher education defines its financial and political limitations. As such there has been a steady increase of private enterprises since the 1980’s developing resources and services that inevitably support the mission of higher education. In recent years we have seen a multitude of collaborative partnerships which range from a 50-year, $483-million lease for parking assets at Ohio State University to a partnership made up of $260 million in cash and savings at Texas A&M, which privatized its dining, landscaping, and building maintenance services. Similarly, we have noticed an increase in P3s in areas such as: enrollment management, online education, data analytics, academic assessment, testing, student housing, student activities, bookstore, media production and marketing, to name a few.

Potential benefits of P3s in higher education can be debated and much of their success is based on the transparency of the relationship established between both entities. Stated benefits include the ability to increase the institutional financial resources, which otherwise would have been allocated to a service now rendered by the P3, the potential opportunity to manage a public operating restriction or state policy, and the prospect of securing new skills and expertise which support the institutional objective.

Similarly the expansive partnerships in online course delivery and development strengthen our ability to serve the growing number of non-traditional students and veterans returning to higher education. This expansion and diversification of delivery is the constant of what Clay Christensen calls disruptive patterns in higher education, in which the introduction of new business model radically transform the operation of an organization (Christensen, 2011). These partnerships continue to evolve to perfect their product, quality, and measureable outcome as a means of decreasing risk while increasing quality assurance.

However, we should also accept the fact that there exist criticisms and pessimistic views regarding P3s in higher education. For example, there is no difference between a privatization and a public private partnership; the public sector loses control of services and governance, quality of service will fall under a public private partnership and cost of service will inevitably increase to ensure profitability.

Lessons Learned

Much has been learned from success and failures of P3s, and as academic leaders explore a partnership as a viable option to support, sustain and promote their mission, the following steps outlined by President Tim Gilmour from Wilkes University should be considered:

- Change does not come easily, therefore prepare your constituencies.

- Support and supply assistance to your leadership, who will need to develop new partnerships outside of the academe.

- Your plan should be based on economic and community principles.

- When possible and preferred invest public funding to “prime the pump.”

- Be selective with your partnership but involve the partnership as quickly as possible.

- Work with the community to release control of non-mission critical activities and focus on how to increase services at lower cost (Cririno, 2007, p 1).

Furthermore, it is imperative to keep in mind that each institution will differ in its approach based on its culture and necessities, however it is advisable to approach a P3 with a balanced perspective that is attentive to not only the institution’s needs, but also those of the potential partner. In doing so, we develop mutual benefits that mitigate project-related risks (Bersnstein, 2015).

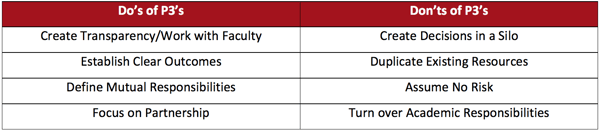

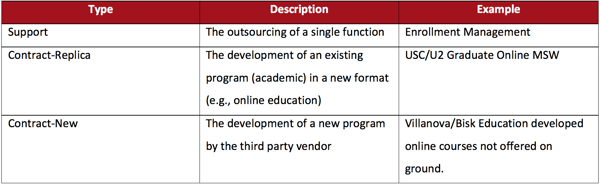

Oblinger (2012) describes the following as examples of academic P3s, each with unique benefits and risks while maintaining academic autonomy by the institutions:

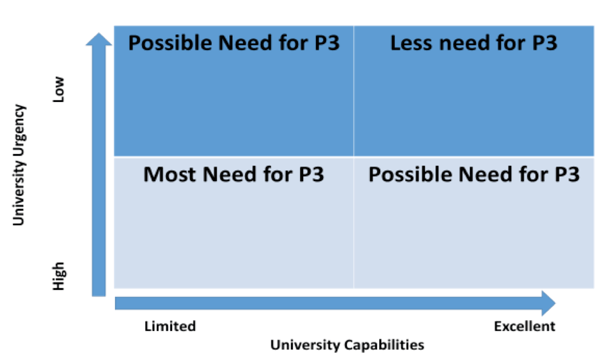

As leaders in higher education often times lament the realities facing their institutions, where access, outcomes and costs continue to be scrutinized and tightened regulatory processes make it difficult to promote and sustain growth, it is inevitable that P3s are recognized as a viable solution. However, the decision to venture into a P3 is not easy nor should it be taken lightly as needs and ability should be considered while measuring the potential high impact as noted by the Decision Quadrant table below.

Summary

Higher education will continue to be a competitive market, but when we couple spiraling enrollment and tight capital, colleges of any size or historical significance begin to fall behind. This downward trend is further substantiated with reduced endowments and declines in state funding, which have impacted hiring, research and capital spending across higher education’s landscape.

The current trends in higher education include: increases of non-traditional students, mandated measurable outcomes, declining resources, and the constant absence of capital to finance growth and innovation. These have become the collective catalyst for the rising demand for P3s, which bring expertise, flexibility, capital and enthusiasm. Hence, P3s are providing opportunities for many institutions to expand access and improve their ability to collect and interpret quality data while delivering much needed financial sustainability.

References

Gilroy, L. (2013). Annual Privatization Report. Higher Education Public Private Partnerships. Updates. Retrieved from http://reason.org

Oblinger, D. G. (2012) Game Changers: Education and Information Technologies. EDUCAUSE. Retrieved from https://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/pub7203.pdf

Cirino, A. M. (2007). The Power of P3. NACUBO Public Private Partnerships. Retrieved from http://www.nacubo.org/Business_Officer_Magazine/Magazine_Archives/July-August_2007/The_Power_of_P3.html

Daniel, L. (n.d.). Public Private Partnerships: It’s the Rights Time: NACUBO. Retrieved from http://www/nacubo.org/Business_Officer_Magazine/Business_Officer_Plus/Bonus_Material/Public-Private_Partnerships_It%E2%80%99s_the_Right_Time.html

NACUBO, “Decision Quadrant for Considering PPPs.” Retrieved from http://www.nacubo.org/Documents/bom/BOM201001F3_Chart1.pdf

Author Perspective: Association