Published on

Newly Released Student Loan Data Bust Several Myths about Student Loan Repayment

Researchers have begun to fill these gaps in our understanding of student loan repayment and default by analyzing student-level repayment data from the National Student Loan Data System (NSLDS) that were released by the U.S. Department of Education last fall (see examples here, here, and here). Initial analyses of these data suggest that at least three commonly held notions about student loan repayment and default may be more myth than fact.

Myth #1: Most students repay their loans within 10 years

The standard repayment period for federal student loans is 10 years. Some students repay more quickly than the standard repayment period by making larger payments, whereas others repay more slowly by enrolling in income-based repayment plans that lower monthly payments for students with lower incomes. Until recently, researchers could only assume that the typical student takes approximately 10 years to repay their loans, because long-term data on loan repayment were not available.

These new data, however, suggest that students take longer to repay their loans. For example, even among those who borrowed only for their undergraduate education (and not for graduate school), only half of students had paid off all their federal student loans 20 years after beginning college in 1995–96. The average borrower in this group still owed approximately $10,000 in principle and interest, about half of what was originally borrowed, 20 years after beginning college.

Myth #2: Most defaults occur in the first few years after students leave college

Many policymakers assume most defaults occur in the first few years after students leave school, a time when individuals may be struggling to find a job or working at an entry-level position. In fact, current federal default statistics measure default only in the first three years after students exit college. Among 1995–96 beginning students, however, more than half of students who defaulted within 20 years of beginning college were in repayment for more than three years before they defaulted. The average time between students entering repayment and their first default was 4.9 years.

Given that more than half of defaults occur outside the window covered by current federal default statistics, overall default rates are much higher than previously thought. Among students who began college in 1995–96, one-quarter defaulted on a federal student loan within 20 years of beginning postsecondary education. Among students who began college in 2003–04, however, one-quarter defaulted in just 12 years after beginning college. Time will tell what their default rate will be at the 20-year mark.

Myth #3: Increasing default rates are caused by increases in student debt

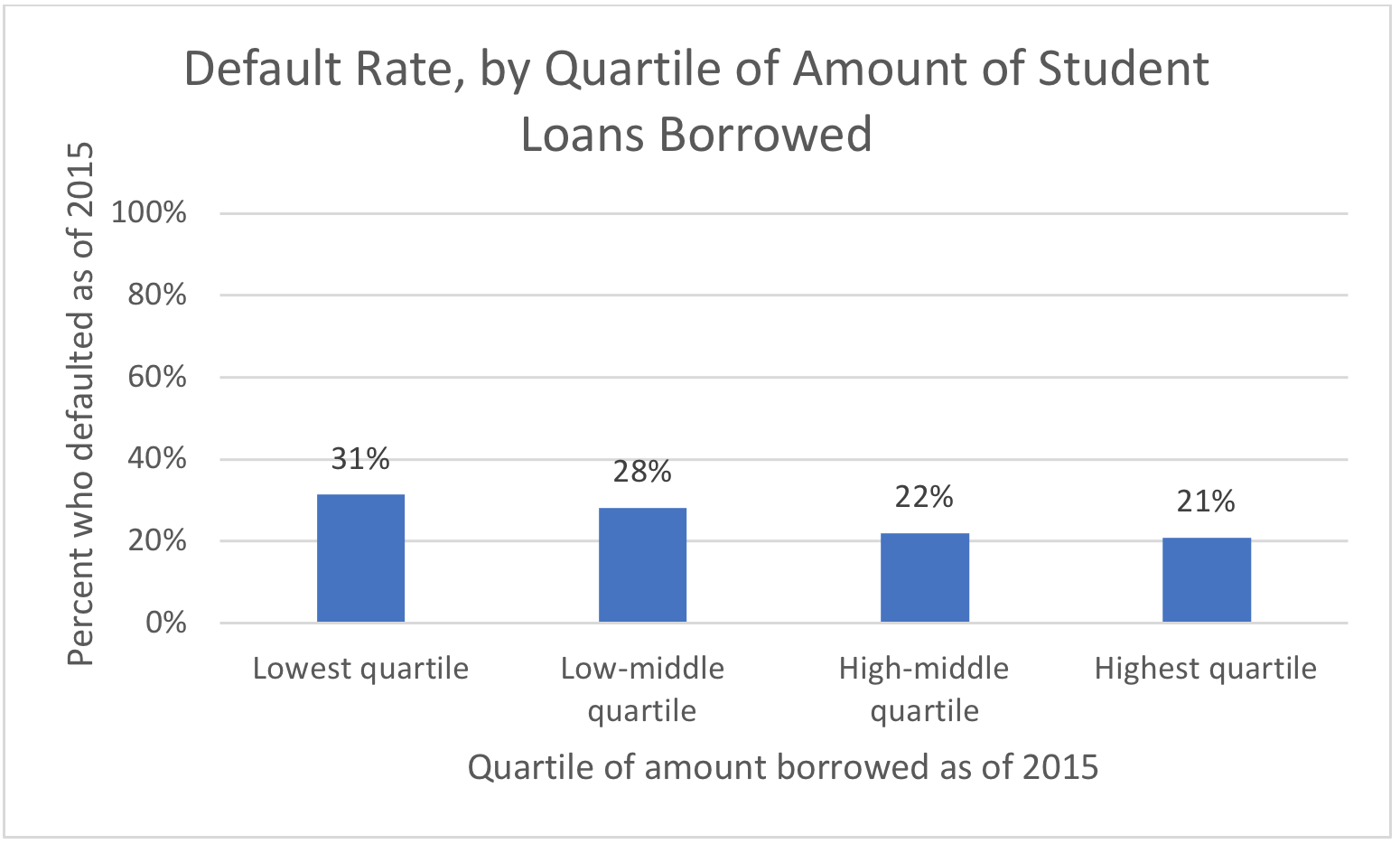

Default rates have been increasing over time. Many have assumed a major cause of this trend is increasing tuition prices, which have led to increased student loan debt. Logically, one might assume that the more debt a student takes on, the harder it will be to repay and the more likely the student will be to default. In fact, those who borrow the most are not the most likely to default:

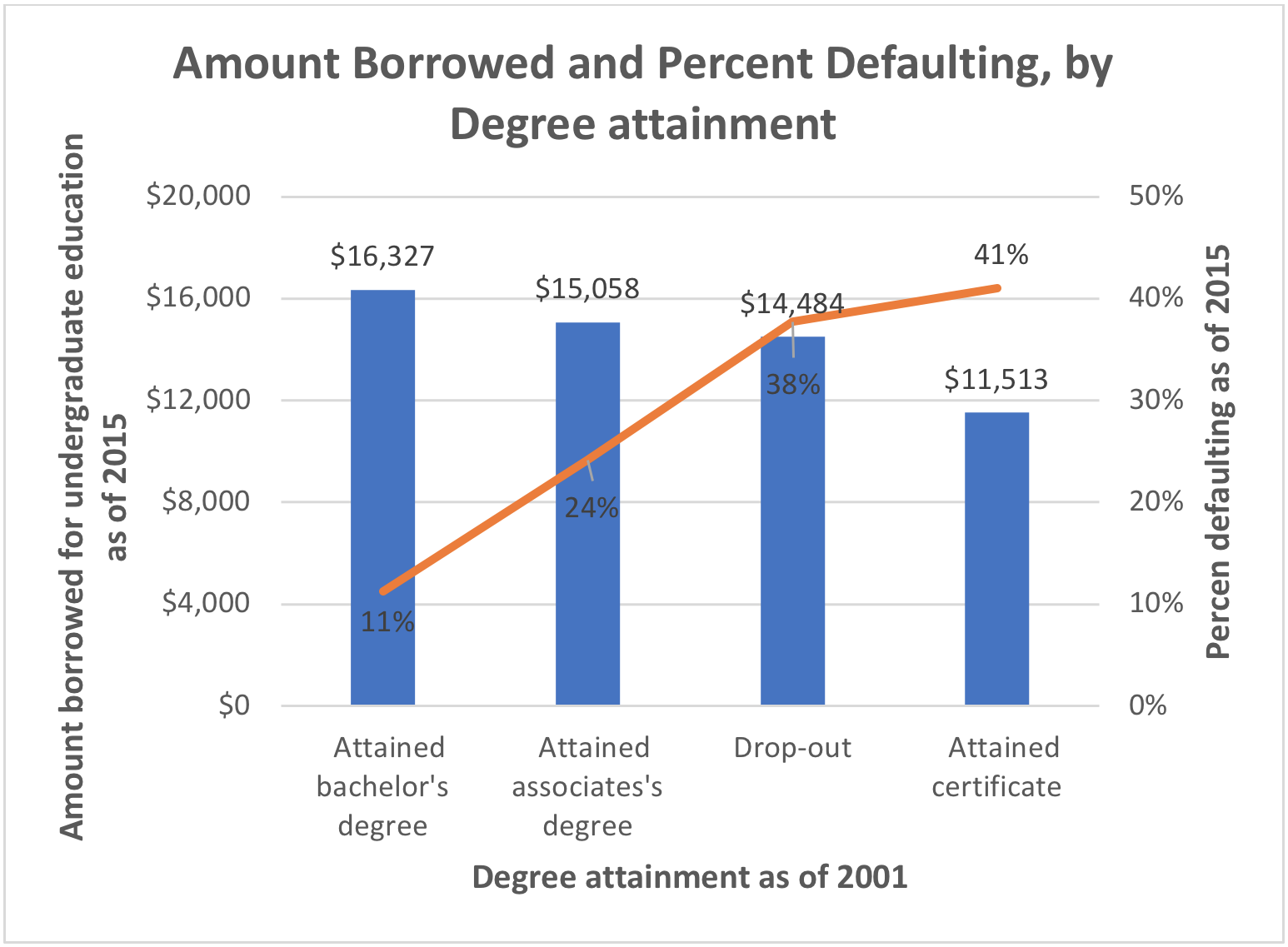

The reason total debt is not related to the likelihood of default is because while borrowing more may make it difficult to repay one’s loans, students who complete degrees also borrow more than students who drop out, and degree completion is a major factor related to default:

As expected, the level of education students attained is associated with the amount they borrowed. Students who obtained a bachelor’s degree borrow more than their counterparts who obtain an associate’s degree or certificate. Those who drop out of college borrow less, on average, than those who attain a bachelor’s or associate’s degree, but more than those who attain a certificate.

But even though bachelor’s degree earners borrow more, they have significantly lower default rates. In contrast, those who earn certificates have much lower debt burdens, but are considerably more likely to default. These data suggest that whether a degree is completed, and the type of degree, may be more important factors related to the increasing default rate than the amount students borrow.

More Detail on the New Publicly Available Data

These findings are based on analysis of the U.S. Department of Education’s 2015 Federal Student Aid Supplements to the 1996/01 and 2004/09 Beginning Postsecondary Student Longitudinal Studies (BPS:96/01 and BPS:04/09). BPS:96/01 and BPS:04/09 surveyed nationally representative samples of students who began college in 1995–96 and 2003–04, respectively, over the subsequent 6 years, collecting information on their postsecondary experiences, degree attainment, and post-college employment. The 2015 Federal Student Aid Supplements append federal student loan records through 2015 to the BPS survey and transcript data. These data allow researchers to examine students’ loan outcomes 12 years after the 2003–04 cohort began postsecondary education and 20 years after the 1995–96 cohort did so. Researchers may analyze the data using the Department of Education’s data analysis website, Datalab or by requesting restricted use data files from the Department of Education.

These statistics are just the tip of the iceberg of the analyses that can be conducted with this new data source. Our hope is that the data can trigger a deeper understanding of loan repayment and how student loans continue to impact borrowers many years after they exit postsecondary education.

Author Perspective: Analyst