Published on

Tips & Techniques for Increasing Student Engagement: The Road to Improved Academic Advising (Part 5)

“If you build it, (they) will come.” So says the voice to Kevin Costner’s character in the 1989 movie Field of Dreams. Unfortunately for academic advising at institutions nationwide, this is not always the case. Despite the best efforts of advisors to promote student success through academic advising programs, not all students are engaged with advising on their campus. Too many are disengaged from advising and not pursuing the right kinds of activities across campus.

Mandatory Advising

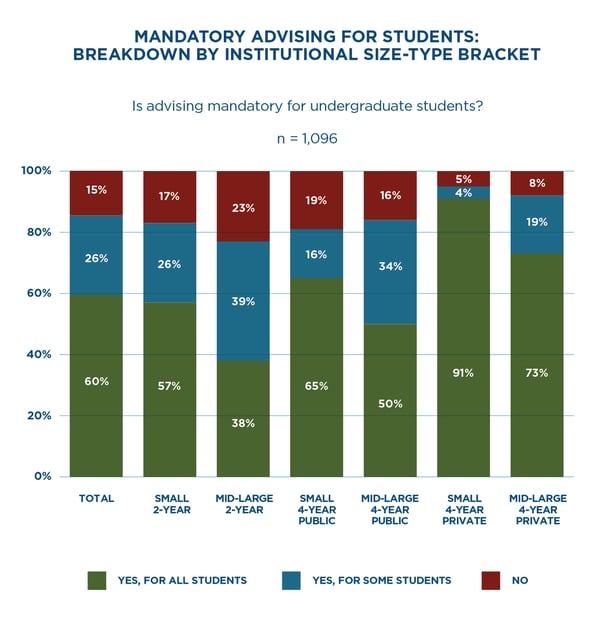

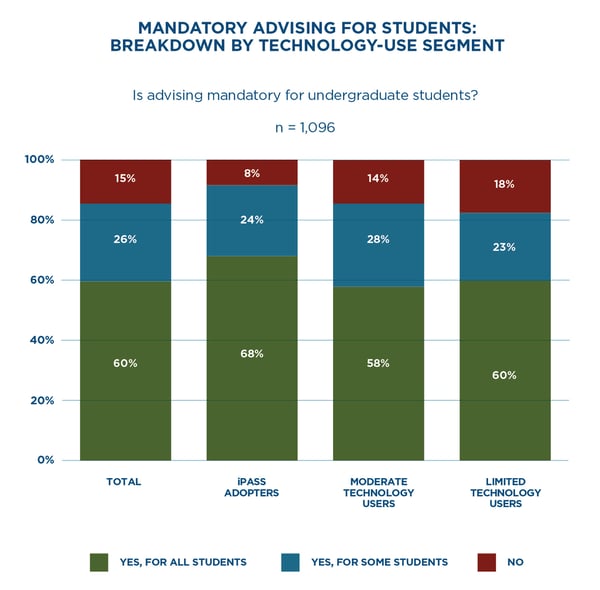

Mandating advising for undergraduates is the most tried-and true technique for increasing student engagement with advising. Sixty percent of the over one thousand respondents surveyed in our report on advising practices and technology, Driving Toward a Degree: Establishing a Baseline on Integrated Approaches to Planning and Advising, mandate advising for all undergraduate students. Another 26 percent of institutions mandate advising for at least some students.

These institutions mandate advising because they understand how integral it is for an advisor to engage with a student, learn about their personal and academic goals and help the student chart a path to success. These institutions also understand that mandated advising sessions may be the only interaction a student has with a university staff member outside of the classroom. This is especially important for first-year and transfer students who are often overwhelmed with not only the rules, regulations and responsibilities of course registration and degree requirements, but also with the many academic and social adjustments needed of new students.

Interestingly, mandatory advising remains a tried-and-true technique even as institutions adapt advising technology. Our research grouped institutions in three segments based on their adoption of technology—limited, moderate and intensive. As the adoption of technology increases across institutions, so do the rates of mandatory advising. This indicates that technology is implemented as a complement to, and not a substitute for, traditional advising.

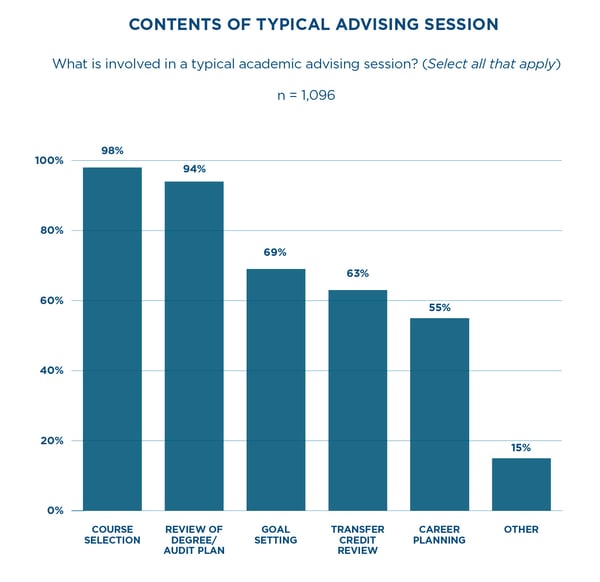

Mandatory advising has its drawbacks, however. Oftentimes student-to-advisor ratios of hundreds of students to one advisor make scheduling mandatory sessions for all students almost impossible. For those sessions that are scheduled, advisors must focus on the critical degree planning or course registration activities. Despite best intentions, the advisor has insufficient opportunity to connect students with who they are, what they are learning, and who they want to become, but instead focuses more practically on academic planning. Course selection and review of degree plans are by far the most frequent topics in a typical advising session as indicated by the respondents we surveyed.

As a consequence, mandatory advising sessions can be too transactional and students feel undersupported.

Other Techniques

1. Peer Advisors

To overcome the problems of advisor overload and transactional advising sessions, one option is peer advisors that augment institutions’ professional advisors’ roles. The benefits are two-fold:

- Peer advisors extend the scope and availability of primary-role advisors, who then have more time to focus on students’ interpersonal interactions, behavior awareness, and decision-making skills.

- Who better to advise a younger student than an older student who has walked a mile in their shoes?

Of course, there are risks with peer advisors. They are acting as representatives of the university and as a sanctioned resource for other students. Extensive training for peer advisors will be necessary. A monitoring system will also be needed to ensure peer advisors are acting in accordance with institutional policies and procedures.

2. Group Advising Sessions

Similar to peer advisors, group advising sessions use the power of shared experience. When students are together, and they make that transition onto a new campus or into a new semester, they suddenly have something special in common. As described by the anthropologist Victor Turner, people experiencing the same event, at the same time and in the same space, are in that sense equals. This has tremendous binding power, and that binding power leads students to turn to each other with questions regarding activities like registering for classes, completing their degree plan, or scheduling an appointment with their advisor.

Moreover, group advising sessions allow institutions to adequately advise students within the constraint of too few advisors. There are challenges, however, in administering group sessions. Special consideration must be given to the size of the groups, how students will be assigned to groups, and how the delivery of content will be similar to yet different from individual advising sessions.

3. Design Thinking

No matter what the technique, it is inevitable that an institution will have disengaged students. To better engage these students, start with the first step in the design thinking process—empathize. Understand the student experience with advising by walking a mile in their shoes. Approach an interaction with an advisor or faculty member from the perspective of a student—who is the student, what is important to them, and what are their feelings toward advising.

Also, be sure to observe and interact with extreme users, i.e., those students who have needs that are in some way heightened (re-entry students, transfer students, international students, etc.), and therefore have to find work-arounds to make advising work. These students will help advisors and administrators identify important needs at the tail ends of the advising bell curve.

As an example of empathy in practice, the Center for Academic Advising, Retention, and Transitions (CAART) at George Mason University conducts focus groups with transfer students to learn more about their needs and how CAART could improve their transition to George Mason. CAART also proactively reaches out to all undeclared students to promote academic advising services, with particular attention to students who are on academic probation or have earned sixty credits.

Taking the first step in the design thinking process is critical because it ensures the right context for subsequent steps. Without empathizing first, steps such as defining the problem, and generating and testing potential solutions can be misguided, leaving an institution worse off than it was before its endeavor to reform advising.

Role of Technology in Promoting Student Agency

While there are certain programmatic steps an institution can take to increase student engagement with advising, it is also necessary to ensure that the technology used to support these steps is intuitive, seamless, and creates a student-friendly experience. First and foremost, this means technology meets students where they are now – on their mobile devices. According to a report published by Pearson, 86 percent of college students regularly use a smartphone, and 51 percent report that they regularly use a tablet. Beyond usage, mobile devices are seen as a fundamental part of colleges students’ lives, Gallup reports 51 percent of 18-to-29-year-olds say they cannot imagine life without their smartphone.

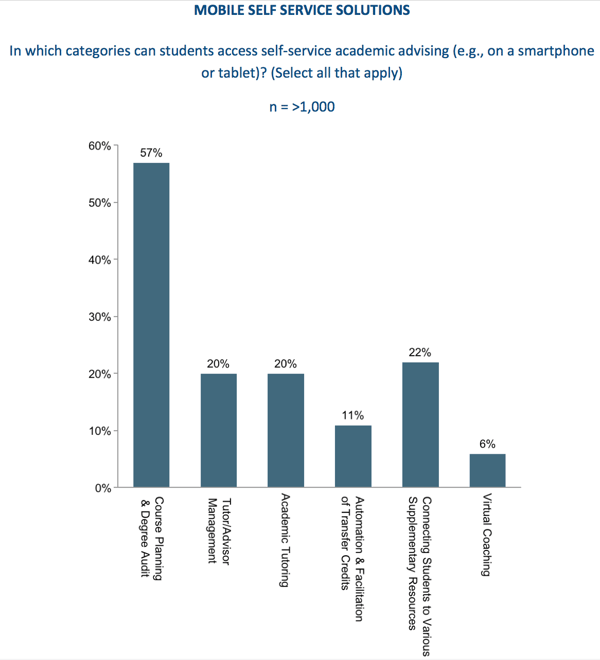

Yet institutions report low rates of mobile student self-service across several advising categories.

More than half of the respondents surveyed indicated that course planning and degree audit is mobile-friendly for students. However, other categories like virtual coaching and academic tutoring reports low rates of student self-service, 6 and 20 percent respectively. Increasing the number of touch points for students with advisors via mobile devices will increase student engagement with advising.

This is the fifth and final installment of The Road to Improved Academic Advising, a five-part series from Gates Bryant and his colleagues at Tyton Partners. Previous installments of the series, in order, are as follows:

- Moving Leadership Beyond Empty Mandates: The Road to Improved Academic Advising (Part 1)

- Achieving Return on Planning and Advising Investments: The Road to Improved Academic Advising (Part 2)

- Getting Advising Stakeholders on the Same Page: The Road to Improved Academic Advising (Part 3)

- Taking Advising Analytics Beyond the Numbers: The Road to Improved Academic Advising (Part 4)